Census 2021 – what will the results tell us about rural England?

Since 1801 a regular Census has been carried out in England and Wales. With the first results from Census 2021 in England and Wales released in June 2022, how will this information be used, and how can we ensure every[rural]body counts? Jessica Sellick investigates.

………………………………………………………………………………………………..

What is the Census? According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNPF), a population and housing census is ‘among the most complex and massive peacetime exercises a nation can undertake….It generates a wealth of data, including the numbers of people, their spatial distribution, age and sex structure as well as their living conditions and other key socioeconomic characteristics’. The UNPF describes the following four key features of a census:

- Individual enumeration: each individual and each set of living quarters is enumerated separately and the characteristics thereof are separately recorded. This allows data on various characteristics to be cross-classified.

- Universality within a defined territory: the census should cover a precisely defined territory (for example, the entire country or a well-delimited part of it). The population census should include every person present and/or residing within its scope, depending on the type of population count required. That is, a census should not cover an arbitrary or vaguely defined sub-population.

- Simultaneity: each person and each set of living quarters should be enumerated as nearly as possible in respect of the same well-defined point of time and the data collected should refer to a well-defined reference period. That is, the enumeration should attempt to present a ‘snap-shot’ of a population to prevent double counting as people move into and out of the unit of enumeration.

- Defined periodicity: censuses should be taken at regular intervals so that comparable information is made available in a fixed sequence. A series of censuses makes it possible to appraise the past, accurately describe the present and estimate the future. This allows time trends to be established with more confidence.

In England and Wales, the Census is undertaken every 10-years by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). ONS describes how: ‘it [Census] gives us a picture of all the people and households…it asks questions about you, your household and your home. In doing so, it helps to build a detailed snapshot of our society’.

When did the Census begin – and how has it changed over time? Back in 4000 BC the Babylonians used a census to determine how much food they needed for their population – indeed the British Museum has examples of the clay tiles they used to record this information. From 2,500 BC, the Egyptians used censuses to identify the labour they needed to build pyramids. And in the sixth-century, the Roman King Servius Tullius started a register of citizens to determine taxes – this exercise was repeated every five years.

In England, its more recent origins can be traced back to 1086 when William the Conqueror wanted to learn more about the kingdom he ruled. He ordered a survey to find out who owned land, how much their possessions were worth and how much tax he could charge them. The results revealed which areas of the countryside were worked as ploughland, pasture, meadow or woodland, as well as identifying regional variations. At the time it was noted that ‘there was no single hide, nor yard of land, nor…one ox nor one cow nor one pig which was there left out and not put down in his record’.

The next survey of comparable scale did not take place until the ‘Hundred Rolls’ in 1255, an exercise carried out for King Edward I, once again to understand which of his subjects had land and power. However, it gathered information from people from all classes and was not confined to wealthy landowners.

It was in 1800 that the Census Act [also known as a Population Act] was passed. Its purpose was to give the Government an understanding of the population. At the time, it was designed to identify how many men could potentially be recruited for future wars. John Rickman, a civil servant, was charged with overseeing the first Census in Britain, and his interest in Censuses has been widely documented. Rather than collect information from individual households, between 1801 to 1841, Britain was divided into district administrations with information collected in aggregate.

It was under the stewardship of Thomas Henry Lister, in 1841, that led Census data to be collected at a household level. Each dwelling received a form which they used to provide information about every inhabitant. A civil servant, known as a enumerator, would then return to collect the forms. The enumerator could also assist householders with completing the form.

George Graham took over in 1842 and oversaw the Censuses of 1851, 1861 and 1871. An increasing focus at this time was organising the data that was returned – to better understand issues such as birth rates and life expectancy.

In 1911 a process of automation began whereby the information contained on forms was processed by machines [tabulated] and then stored on cards with punched holes in them. The individuals forms were also stored so that householder’s writing could be seen rather than a enumerator’s description.

The Census Act 1920 allowed for a Census to be taken every 10-years without further primary legislation. Since then, each Census has required two pieces of secondary legislation to take place: a Census Order [sets out the topics to be covered] and Census Regulations [how to take the Census and the questions it will contain].

Between 1911 and 1921, and again in 1939, population information was collected to understand the effects of war on labour, the impact on mass evacuation and rationing. The results of the 1931 census were destroyed in a fire in December 1942.

More in-depth analysis of the census was enabled in 1961 when the automation process was enhanced and computers were introduced to process data for the first time. After 1961 the next census was undertaken in 1966 because politicians felt they needed a better understanding of societal shifts.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) first ran the Census in 2001 – the first one where you could post back forms rather than waiting for a enumerator to go door-to-door. Since 2011 it has been possible for households to complete the census online. In 2021, 88.9% of householders completed their census online, with no paper forms sent out unless requested.

Since the Census began the types of questions it asks have evolved. For example, from 1821 people’s ages were first recorded, in 1831 information about the industries in which people worked, and in 1841 household inhabitants were asked where they had been born not just where they were living. More recent additions include asking people about outdoor toilets (1951), their ethnicity (from 1991); religion (2001); and veteran status, sexual orientation and gender identity (since 2021). Some of these questions are voluntary and/or limited to respondents aged 16 years and over.

From having a better understanding of land holdings, to war recruitment and societal shifts; and from using a enumerator to a digital-first approach, the census has a long history – and over the years its systems have changed and evolved.

What is the purpose of a Census? A Census is a snapshot of a population at a point in time. The UN describes how a Census generates data that is ‘critical for good governance, policy formation, development planning, crisis prevention, mitigation and response, social welfare programmes and business market analyses’. In the UK, because the same questions are asked, and the information recorded, it allows us to compare different groups of people.

The Census collects information on a range of topics and provides a level of detail for small population groups and/or geographic areas that is not possible in other Government surveys.

What do the results tell us? Information given to the Census predicts the demands upon, and informs the financing of, public services. For example, Government uses the data to calculate the size of grants it allocates to Local Authorities. Councils use Census data to develop policies. NHS planners use data on general health and long-term illness to design health and social care interventions.

Census data is also used by a wide range of stakeholders. Voluntary and Community Sector organisations, charities and community groups, for example, use Census information to help them get a clearer picture of who makes up their local community. For academics the Census is a research resource – supporting longitudinal studies and/or surveys to enhance the data by looking at current outcomes or predicting future trends. Census data is used by businesses for market research purposes, to develop new products and services and/or to target their marketing.

The last Census for England and Wales was carried out by the ONS in March 2021. In June 2022, ONS published population data (by age and sex) by Local Authority area.

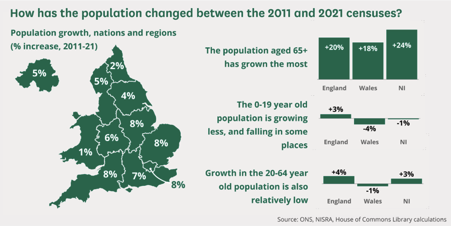

This reveals how the number of people in England and Wales has grown by more than 3.5 million (6.3%) since the last census in 2011, when it was 56,075,912. The population grew in each of the nine regions of England and Wales. The region with the highest population growth was the East of England, which increased by 8.3% from 2011 (a gain of approximately 488,000 residents). There were 30,420,100 women (51.0% of the overall population) and 29,177,200 men (49.0%). There were more people than ever before in the older age groups; the proportion of the population who were aged 65 years and over was 18.6% (16.4% in 2011).

House of Commons Library Insight

These first results and the graphics above illustrate how the trend of population ageing is continuing. While there are more people in the 15-64 years age group compared with 2011 (when there were 37.0 million people), as a proportion of the overall population there has been a slight decrease in the size of this group (compared to 65.9% in 2011).

Across England and Wales, Local Authorities with the highest percentages of the population aged 65 years and over were North Norfolk (33.4%) and Rother (32.4%). East Devon had the highest percentage of the population aged 90 years and over (1.9%), followed by Rother (1.8%).Compared with the other English regions, London had the largest percentage of people aged between 15 and 64 years (70.0%).

What about rural areas? The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs presents Census data in the Statistical Digest of Rural England. The July 2022 edition, for example, collates statistics on social and economic subject areas, and splits them by rural and urban areas, allowing for comparisons.

Rural areas have a higher proportion of older people compared with urban areas. If we want older people to live independent, healthy, and fulfilling lives in rural areas this population data emphasises how we need to address the key challenges experienced by those wanting to age in place – from having a long-term plan for formal care services to supporting informal care. Alongside this, there has been less specific public policy reference to children and young people living in rural areas. Those aged 20-24 years show the largest outmigration. If levelling-up is about children and young people in every part of the country being prepared with the knowledge, skills and qualifications they need, how can we ensure this supports young people to have a stake in the countryside and supports young people to remain in or move to rural areas?

It is worth noting that when the Census was completed, in March 2021, England has national coronavirus restrictions. This means the Census may ‘overcount’ the total number of rural dwellers in ‘normal times’ due to the number of urban residents moving to the countryside during lockdown periods. Will rural areas gain or lose if householders have been over or under counted?

A topic summary is a set of data and supporting commentary, grouped by a similar theme. ONS will be releasing topic summaries in the following order: demography and migration, ethnic group, armed forces veterans, housing, labour market and travel to work, sexual orientation and gender identity, education, and health and care. The first topic summary is due to be published in October 2022. The final release of Census 2021 outputs is expected in spring 2023, and the last publication of articles in summer 2025. What will this reveal about rural areas?

How many people are missed? The Census is the largest statistical exercise that the ONS undertakes. Their aim is to count everyone once, in the right place, and for questions to be completed accurately. ONS has a methodological approach for adjusting the count for individuals who were not counted or were counted more than once. Known as statistical design, this sets quality targets for residential address coverage, and indices to use to predict how and when people respond to follow-up with non-responding households. Even with a variety of strategies to maximise responses, coverage errors occur when a person is counted more than once or not counted. In the 2011 Census, for example, ONS estimated undercoverage to be 6% and overcoverage 0.6%. Public funding is often allocated on the basis of Census data, therefore missing data points can equate to missing pounds.

Where next? ONS has a responsibility to ensure the results of the Census are accurate and follows the Code of Practice for Statistics set by the UK Statistics Authority. For Census 2021 ONS assessed its entire operation against the Code. Indeed, ONS held a rehearsal in 2019 to test the processes, systems and services to be used for Census 2021. ONS is currently engaging with users to gather their views and experiences of Census 2021. In 2023, ONS will make a formal decision and recommendation about carrying out a Census in 2023. In the meantime, there have already been discussions around whether this decennial questionnaire would be better served by an annual data snapshot instead. Will we find an alternative way(s) of delivering a future Census? And how can we make sure rural counts? Watch this space…

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

Jessica is a researcher/project manager at Rose Regeneration and a senior research fellow at The National Centre for Rural Health and Care (NCRHC). She is currently supporting a Community Renewal Fund project; and evaluating employability schemes and a veterans programme. Jessica also sits on the board of a Housing Association that supports older people and a charity supporting Cambridgeshire’s rural communities.

She can be contacted by email jessica.sellick@roseregeneration.co.uk.

Website: http://roseregeneration.co.uk/https://www.ncrhc.org/

Blog: http://ruralwords.co.uk/

Twitter: @RoseRegen