How can we maintain a universal postal service in rural areas?

The ‘one-price-goes-anywhere, six-days-a-week’ Universal Service Obligation has been seen by successive Governments as part of our social and economic fabric. But do the requirements of the universal service reflect the needs of rural users – and how can we ensure the service is financially viable and sustainable? Jessica Sellick investigates.

How does the UK postal market operate – and what is the universal service obligation? Between 2007 and 2008 an Independent Review of the Postal Sector was led by Richard Hooper. The Review was established to maintain the universal postal service – the collection, sorting, transportation and delivery of letters to all business and residential addresses in the UK. Hooper published his first report in December 2008. The report both highlighted the rationale of the universal service – its affordability, uniform tariff, and deliveries on six-days-a-week – and how it was under threat with digital media prompting a decline in the letters market. With a proposition that the status quo was untenable, the report suggested Royal Mail needed to accelerate its restructuring plan and modernise faster if the universal service was to be sustained. In September 2010 Hooper published an update to the 2008 review. He found the underlying issues that threatened the viability of the universal postal service remained high and that urgent action still needed to be taken. Both reports contained similar recommendations around regulatory reform, relief of the pension deficit, and the need for private sector capital.

The Postal Services Act 2011, introduced by the Coalition Government, received Royal Assent on 13 June 2011 and was fully implemented on 20 December 2011. This legislated for the recommendations contained in Hooper’s reports. The Act is divided into five parts. Part 1 set out the restructuring of the Royal Mail group of companies. Part 2 contained arrangements for the Royal Mail pensions scheme. Part 3 explained the regulation of the postal services sector. Part 4 described provisions for a special administration regime to secure the universal postal service. Part 5 contained other general provisions, regulations and matters made by the Secretary of State. The implementation of the Act saw the regulation of postal services transfer from Postcomm to Ofcom, and created a new regulatory framework that not only provided a universal postal service to Royal Mail but also allowed it greater freedom in the pricing of stamps and parcels. The Act also separated the post office network from Royal Mail – and relieved the Royal Mail Group of the deficit in the Royal Mail Pension Plan (RMPP) by transferring responsibility for its funding to the Government.

In October 2013 Royal Mail launched a share offer to raise money to finance the business. In addition to members of the public being able to buy shares, full-time staff at Royal Mail received 725 shares each, worth £3,545 at that time.

Various policy documents from successive Governments have set out the primary objective in relation to Royal Mail and postal market reforms as being ‘to safeguard the universal postal service in the UK. The one-price-goes-anywhere, six-days-a-week universal postal service provided by Royal Mail is part of the social and economic fabric of the United Kingdom.’ Royal Mail is not only the UK’s largest postal operator, but also the only operator that meets the UK’s Universal Service Obligation (USO).

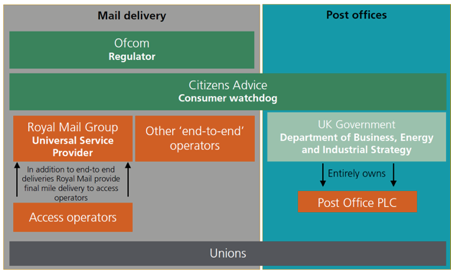

Who’s involved in the UK’s postal market? The diagram below provides a map of postal services in the UK:

There are two types of letter delivery: (1) end-to-end services where the same postal operator undertakes the entire process of collecting, sorting and delivering mail; and (2) access services where an operator collects and sorts the letters but then hands over final delivery to Royal Mail. Royal Mail is obliged to open its network to access providers. While the majority of the letters market sits with Royal Mail, the parcel’s market is highly competitive with multiple brands operating in this sector. The Royal Mail Group is a limited company which has multiple business units: UK Parcels International & Letters (domestic), General Logistics Systems (European), and Parcelforce Worldwide (global).

The Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) has Government responsibility for postal matters. In 2018, BEIS published a Post Implementation Review of Parts 3 and 4 of the Postal Services Act 2011. The Review found the Act was meeting its objectives of securing the financial sustainability of the universal postal service and had made good progress towards other objectives. The Review highlighted how Royal Mail had gone from lost-making to profitable since the Act was introduced – with an EBIT margin – Earnings Before Interest and Tax – of 4.6% [just outside the 5-10% range that Ofcom considers consistent with a reasonable commercial rate of return]. The Review also found that the regulatory regime was providing strong incentives for Royal Mail to find efficiencies and that savings within the business had contributed to its financial improvement. An increase in competition in the parcel delivery market was seen as bringing significant benefits to the users of postal services.

Royal Mail is a fully privatised company and its performance, in line with current legislation, is monitored by Ofcom. Ofcom publishes an annual monitoring update on the postal market. The latest update, published in November 2020, describes how “2019-2020 was a challenging year for Royal Mail. Its financial performance was weaker than in previous years; and issues facing the business due to the changing market and consumer trends were apparent even before COVID-19 started to have an impact”. Drawing parallels with Hooper’s reports, the update identifies how Royal Mail needs to modernise its network, keep pace with parcel customers’ changing requirements, and manage the costs associated with higher parcels volumes. Unless it is able to become more efficient, and adapt to a changing market, the Update concludes that this could put the sustainability of the universal postal service at risk in the longer term.

Also in November 2020, Ofcom published a review of postal users’ needs. The review found the current USO service levels – the six-days-a-week letter requirement – was meeting the needs of 98% of residential users and 97% of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in the UK. Reducing the letter service to five-days-a-week, but leaving all other elements of the USO unchanged, would still meet the needs of 97% of residential and SME users. Ofcom found little variation in users’ views on five-day letter delivery across the UK or according to how remote users’ locations were. Ofcom’s research therefore suggests that reducing the frequency of letter deliveries to five-days would reflect users’ reasonable needs and would potentially allow Royal Mail to make net cost savings of £125-£225 million per year from 2022-2023. It is for the UK Government to determine whether any changes are needed to the minimum requirements, and to bring any proposals before Parliament. Ofcom’s research forms part of a review of the future regulatory framework for post. The Review will consider issues affecting the broader postal sector including access regulation for letters, consumer issues in the parcels and letters markets, and how regulation can support a modern well-functioning parcels market that delivers benefits to end users.

Citizens Advice (England and Wales), Citizens Advice Scotland and the Consumer Council for Northern Ireland were given statutory responsibilities to represent consumers of postal services back in 2014. These organisations provide policy advice, deliver projects and ensure consumer needs are represented in the operation and improvement of the postal market in a way that is ‘fair and accessible to all’ and takes account of the needs of vulnerable consumers. Citizens Advice publishes regular updates about the performance of postal services in England and Wales. POSTRS is an independent body that mediates disputes between regulated postal operators, including Royal Mail Group, and its customers. Delivery Law UK provides comprehensive information to consumers and businesses on their rights and obligations in relation to parcel delivery. The website is designed and managed by The Highland Council and Trading Standards Scotland on behalf of the UK Consumer Protection Partnership (CPP).

143,000 people are employed by Royal Mail in the UK – some 1 in every 192 jobs – with 99% of employees on permanent contracts. According to Royal Mail, around 87% of operational and administrative-grade employees are members of the communications union (CWU). Approximately 65% of managers are members of Unite/CMA. In total, around 98% of employees are covered by agreements with these two unions.

Will the modernisation process help to maintain the universal service obligation? Since 2006, Royal Mail has been undergoing a modernisation programme. This is focused on six key areas:

- Delivery – more efficient delivery routes, using a blend of technology and people to find the best and most efficient ways to deliver mail to your local area.

- Collection – changing the way they collect mail from postboxes including collection from low use postboxes by people out on delivery.

- Equipment – investing in equipment which is safer and more secure for transporting mail.

- Processing network – investing in modern buildings, sorting machinery and more efficient ways of working.

- Hand-held scanners – to give better and quicker visibility of the mail you are sending or receiving.

- Parcel sorting machines – to speed up parcel sorting and delivery and keep packages in even better condition.

Since 2014 Royal Mail has changed the way it collects letters from post boxes. In response to falling letter volumes, sometimes collections are made at an earlier time, with the mail collected when a postman or woman is making their deliveries. In 2018-2019 Royal Mail handled around 1.3 billion parcels and 13 billion letters. In 2019 Royal Mail commissioned PWC to provide an independent view on the long-term outlook for UK letter volumes. PWC predicted that the total volume of letters would fall from 10.3 billion in 2018 to 6.2 billion by 2028. They attributed this decline to the continued growth in e-platform substitutes, economic uncertainty and a decline in commercial letters as companies focus on digital platforms.

In July 2019, Royal Mail published its UK transformation plan. Under the strapline ‘turnaround and grow’, the Plan covers a five-year period and is centred on Royal Mail developing new ways of working while extending its current network. The Plan has a renewed focus on improved service, efficiency and productivity supported by the implementation of digital tools and investment. The Plan will see £1.8 billion invested in the UK’s postal service over the five-year period which are intended to help fund the Universal Service. This includes the introduction of a second delivery for parcels by 2023 so that products purchased online from retailers are delivered in less than 24 hours from the order being placed [the ‘night owl’ shopping phenomenon]; the construction of fully-automated parcel hubs (once operational these will be able to process more than 600,000 parcels a day); a range of new customer service initiatives including collecting returns from customers at their home and providing in-flight redirection options for customers when their parcel is scheduled to arrive while they are out; and the continued roll out of 1,400 parcel postboxes.

More recent initiatives from Royal Mail include: ‘labels to go’, a service available in post office branches allowing customers to use their mobile phones to print free returns labels; a mobile app to help consumer to track their items; and a parcel pick-up service called Parcel Collect.

On 1 January 2021, the price of stamps increased – by 9p for first class (with a stamp now costing 85p) and by 1p for second class (with a stamp now costing 66p). In a press release on 1 December 2020, Royal Mail explained how the changes were necessary ‘to help ensure the sustainability of the one-price-goes-anywhere Universal Service’.

What impact has COVID-19 had on postal services? Royal Mail has made changes to collection and delivery services as a result of the pandemic. For example, customers are no longer required to sign for a delivery, with the name of the person accepting the item logged instead. Royal Mail is also collecting completed test kits from priority postboxes or from people’s homes as part of NHS Test and Trace.

In June 2020 Royal Mail published its Full Year 2019-2020 Results and Business Update. This revealed how for the first two-months of the Financial Year 2020-2021, while parcel volumes increased by 37% as more people shopped online prompted by the pandemic, total letter volumes declined by 39% leading to a drop in revenue of £29 million. At the same time, overtime and agency costs, PPE and social distancing cost Royal Mail £53 million and operating profit was down £108 million. The document presents 2 scenarios for the future. Under scenario 1, UK lockdown restrictions would continue to be eased from June 2020 – this scenario would see the negative reduction in letters reduce but still lead to £140 million cost to Royal Mail. Under scenario 2, a downside stress test, another lockdown would be implemented in late 2020 and this would cause letter volumes to remain significantly depressed, leading to a reduction in domestic and international parcel revenue and restricted volume growth during the Christmas period culminating in a financial cost of £155 million.

According to Royal Mail, lockdown and the pandemic have seen an increase in start-ups and ecommerce. During the period March-July 2020, 315,000 companies were incorporated in the UK – a 7% increase compared to the same period in 2019. In the second quarter of 2020 (April to June), 176,000 start-ups were recorded, the highest for any second quarter on record, exceeding the previous record high set in 2016. These findings mirror with what has been happening in Royal Mail’s delivery network which is seeing a substantial shift in its business from letters to parcels.

A survey by Royal Mail in June 2020, found just over half (51%) of the 2,000 adults they surveyed agreed that having their online shopping delivered was a ‘boost’ for them or their family; and a third (36%) described the joy of receiving a parcel as the highlight of their day. When asked to name their most unusual parcel delivery since 23 March 2020, responses ranged from home casino kits and Venus fly traps, through to wrestling boots and a full replica model of The Flying Scotsman train!

As the Universal Services Provider Royal Mail’s performance is measured against a number of targets it is required to report to Ofcom [known as DUSP Condition 1]. Failure to meet these targets could result in Ofcom imposing a fine upon Royal Mail. Royal Mail is the only postal operator in the UK required to publish quarterly Quality of Service reports – with their performance independently measured by a market research agency called Kantar. Two of Royal Mail’s key targets are: (1) for first class mail – a minimum of 93% delivered the next working day; and (2) for second class – a minimum of 98.5% delivered within three working days. Royal Mail exceeded the target for second class mail in the 2019-2020 financial year but missed the target for first class mail. Until 15 March 2020 Royal Mail believed it was meeting the first class target (at 93%) however when taking account of the impact of COVID-19 from 29 March 2020 to end of May 2020 the figure dropped slightly to 91.6%. Royal Mail has not been able to fully measure Quality of Service since March 2020 and is in discussions with Ofcom around the impact of the pandemic.

What does modernisation and COVID-19 mean for postal services in rural areas? There have been concerns that parcel deliveries in parts of Scotland and Northern Ireland are unfairly high. In 2019 the Scottish Government published a briefing which estimated the additional cost to Scotland of parcel delivery surcharges relative to the rest of the UK. This estimated that parcel delivery surcharges for 2019 equated to £40 million, an increase of 11% when compared to £36.3 million in 2017. Ofcom’s monitoring report on the postal market for the financial year 2016-2017 also explored surcharges – suggesting a correlation between the areas where at least one provider used a third-party operator to deliver and the areas where operators were applying surcharges. Ofcom found operators were paying varying prices per parcel to third parties from £2.32 to £4.56 per parcel. Parcel operators who provided evidence to Ofcom highlighted three factors which had led them to introduce parcel surcharges: (i) in areas with ‘low drop density’ i.e., a low frequency of deliveries in one area; (ii) in areas requiring transportation over water; and (iii) in areas which are a long distance from the nearest network hub where the operator sorts and distributes parcels.

A report by Citizens Advice Scotland recommended that public and private sectors work together to reduce costs and that Scotland’s network of ‘pick up and drop off’ points be extended to help reduce costs for delivery companies.

In follow-up work, in August 2020, the Scottish Government published further research on surcharges. This found, with the exception of Royal Mail, four of the other largest parcel delivery operators charged surcharges in some parts of the Highlands and Islands. The amount that retailers pay is variable – because they negotiate with parcel operators – which means the amount consumers then pay is also differs, with some retailers absorbing all of the cost and others charging consumers more than the operator is charging them for delivery.

In 2019, the U.S. Postal Service Office of Inspector General (OIG) published a report providing a historical perspective on how the Office has dealt with demands for postal services from rural and urban communities. Rural areas have historically been more costly to serve and did not get postal services at the same rate as urban areas. For example, while home delivery came to cities in 1863, rural areas did not get it until 1896. The US Congress has played a key role in shaping postal policy throughout history, particularly in rural areas where it worked on granular issues such as the selection of specific delivery routes. Also in 2019, the OIG analysed what rural customers across the country needed and want from the US postal service (USPS). The OIG’s survey indicates that rural customers are less likely to receive mail or a package delivery at their physical address. For packages, the Postal Service uses ‘parcel lockers’ as one way to store a package until a customer is able to pick it up. While the survey reveals that most rural and non-rural customers receive similar numbers of packages and order similar sorts of items, the median customer who is ineligible for door delivery receives about the same number of packages as other customers (on average two packages per month), and this makes rurality an important consideration in the Postal Service’s current and future plans to strategically expand parcel lockers.

Both the Scottish research and the OIG survey highlight the importance of having a reliable and affordable universal delivery postal service in rural areas, particularly with the growth in the parcels market and given other delivery options may be more limited or costly for rural residents.

In 2019, Copenhagen Economics was commissioned by the European Parliament’s Committee on Transport and Tourism (TRAN) to conduct a study on postal services in the EU. The study provided an overview of the current state of the sector, future challenges and opportunities, and made recommendations to policymakers on what could be done to stimulate growth and competitiveness in the sector. The sector generates revenues of £79 billion Euros per year, which corresponds to 0.5 per cent of the EU’s total GDP; and the postal and delivery sector employs around 1.7 million people across the EU, corresponding to 0.8 per cent of the employed population. In the EU, the Postal Services Directive sets minimum requirements (although subject to certain exceptions) for the providers of the universal service obligations. The elements of the USO have been unchanged since 1997, but each Member State is free to choose the precise scope and size of the USO at a national level, as long as it fulfils the minimum requirements set out in the Directive. The findings of the study echo those of UK studies: the EU postal sector is also evolving as a consequence of the digital transformation – while the letter segment is still highly concentrated, it is shrinking overall, as digital communication alternatives compete with letter post products. The situation in the parcel segment is different: markets are fragmented, universal service providers share of deliveries are relatively low, and new delivery players entering the parcel segment are challenging incumbents’ business models and profitability.

Maintaining a USO has led some Member States to change the delivery model for rural areas. In 2015 legislative changes in Italy allowed Poste Italiane to implement an XY delivery model in the most rural areas of the country, where mail is delivered on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays during the first week and on Tuesdays and Thursdays in the second week. In Finland, between 2010 and 2013, the Finnish postal operator undertook several pilots for electronic delivery in rural areas, scanning letters and daily newspapers and delivering them in digital form. The pilot was successful from the perspective of residents, but the scanning was too expensive for the postal operator who decided to discontinue the service.

Australia Post commissioned Deloitte Access Economics to develop a deeper understanding of the economic and social value associated with its activities in regional rural and remote Australia. Their report, published in 2020, highlights how through its delivery network, Australia Post enables residents in Regional and Remote areas to make e-commerce purchases, with almost 36 million parcels collected in regional post offices and hubs in Financial Year (FY) 2019. Approximately half of regional Australians make an online purchase requiring delivery at least once a month, and the total value of e-commerce in regional areas is estimated to be over $10 billion Australian Dollars in FY2019. Regional Australians value Australia Post’s services highly enough that they would be prepared to pay between 21% and 45% above the actual price they are currently charged. Australia Post’s national network also means it can facilitate the delivery of services by other organisations: for example, the State Library of South Australia emphasised the importance of this network in enabling the movement of library books between regional communities.

With many Australians staying and working at home due to COVID-19, to meet the unprecedented parcels demand. Australia Post has established 18 new or recommissioned parcel processing facilities, chartered additional freighter flights, is operating some of its processing facilities 24/7 and has employed hundreds of temporary staff. In April 2020, the Australian Government announced temporary regulatory relief to assist Australia Post to continue providing important postal services for all Australians during the pandemic. Australia Post is also transitioning to a temporary alternate day delivery model. Interestingly, this means that in metropolitan areas, Australia Post will deliver regular letters every second business day. However, delivery frequency in regional, rural and remote Australia will not change, and post office boxes will continue to be serviced every business day.

In some countries postal workers have expanded the services they offer beyond letter and parcel delivery. In Denmark and Sweden, for example, Post Nord runs a rural postal service for people who have difficulty collecting mail themselves. The service includes delivering mail to the front door if they have difficulty getting to the mailbox on their property; distributing letters, parcels and additional services (e.g. cash on delivery); collecting letters and parcels that they wish to send; and delivering stamps.

Since 2013, Jersey Post has been operating a ‘Call&Check’ service. The service is carried out by Jersey Post staff who ask the person they are visiting some short questions to find out if any support or help is needed. The Call&Check support team pick up any requests via an IT system. They then work with trusted contacts such as close family members or a GP, or anyone else nominated to give support. Services offered include organising home grocery and prescription deliveries and arranging transport to appointments at the hospital. Pre COVID-19 Call&Check members were also invited to regular social events to get together with friends and meet new people over tea and cake. Research from IBM in August 2020 explored how COVID-19 has exacerbated loneliness. During the pandemic, the service has been adapted, leveraging the telephone for daily virtual visits and sharing the information with authorised caregivers. The service presently costs £6.75 per visit.

In France, since 2017 La Poste has been running the ‘Veiller sur mes parents’ (‘watch over my parents’) service to reassure customers that their parents or relatives are in good health. The postmen and women pop in to have a chat for between five and 10 minutes while on their daily rounds. They have a list of questions such as “Are you well?”, “Do you need any shopping?” and “Do you need a doctor?”. Once they have the answers, the person signs that the information is correct and the replies are sent by text or email to the relative via an app, and to a pre-decided list of other people who have agreed to be contacted if necessary. There are contracts for between one and six visits a week, costing from €19.90 a month, which promises one visit per week, to €139.90 for six visits. Included in the package is an alarm system with a wrist strap with a button to connect the person to a call centre in an emergency. There is also access to a platform where advisors can put the person in touch with local contractors if something needs fixing in their home.

In February 2021, the CWU suggested frontline postal workers could deliver prescriptions while doing their daily rounds in England, and families could pay for relatives to be visited by their postman or woman and have their wellbeing checked. This recognises how postal staff already do a lot of work for their community voluntarily and could formalise the support they provide. Expanding the role of postal workers could diversity and grow Royal Mail and help underpin the Universal Service Obligation. It could also build on the ‘Feet on my Street’ scheme. Funded by the Home Office as a pilot in New Malden, Liverpool and Whitby in 2018, the scheme sought to understand if tackling social isolation in older people made them less likely to become the victim of crime. Postal staff asked people five standard questions about their welfare and connected them into services if/where necessary. While the pilot was deemed a success it was never followed up or rolled out.

Where next for the postal services market? The one-price-goes-anywhere delivery of letters, packets, parcels and other items to all UK residential and business addresses in the UK is highly prized. Royal Mail is the only company that is – and can currently provide – a universal postal service in the UK. With declining letter volumes, an ever more competitive parcels market, a review of the regulatory framework underway, a potential reduction in the frequency of letter deliveries from six to five-days and the impact of COVID-19, ensuring the USO remains financially viable and sustainable remains a challenge.

Urban areas often have enough consumers to prompt the emergence of more than one service provider, which can lead to low prices and highly efficient supply chains. However, rural areas do not have always have the ‘critical mass’ and this is where there is risk of market failure and in relation to postal services mechanisms may need to be put in place to ensure residents and businesses can access postal services. For Royal Mail there could be new opportunities to diversify its income streams, particularly in rural areas – for example, offering something akin to the Call&Check or ‘watch over’ service for older and vulnerable residents as part of COVID-19 reset and recovery.

We need to be clearer not only on how much it actually costs to provide postal services in rural areas; but also the economic and social value that this brings (e.g. helping people to maintain their independence and wellbeing, reducing social isolation, increasing access to services etc.). What would happen if we did not have a USO (or reduced USO) and/or if the largest provider no longer wanted to fulfil the USO – would other providers step in to serve our rural communities?

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

Jessica is a researcher/project manager at Rose Regeneration and a senior research fellow at The National Centre for Rural Health and Care (NCRHC). Her current work includes supporting health commissioners and providers to measure their response to COVID-19 and with future planning; and evaluating two employability programmes helping people furthest from the labour market. Jessica also sits on the board of a Housing Association that supports older and vulnerable people.

She can be contacted by email jessica.sellick@roseregeneration.co.uk.

Website: http://roseregeneration.co.uk/ https://www.ncrhc.org/

Blog: http://ruralwords.co.uk/

Twitter: @RoseRegen