Targets as a public policy tool: do we need more or less?

Targets are widely used in the public sector and beyond. For some people achieving them is viewed as a marker of success while for others they remain controversial. Indeed, some people think ‘targetry’ should be limited, reduced or scrapped altogether, while others want more. Why set targets, and what makes a good [and less good] rural target? Jessica Sellick investigates.

………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Since the 1980s, successive Governments have pursued various approaches to develop performance measurement, reporting and management systems for public bodies. While hospitals have collected activity data since the 1950s it was in the 1980s that the NHS began programmes of measuring and reporting on the performance of NHS bodies. At the same time, measurement work began in local government, education and nationalised industries. While some of this work was driven by central Government, others originated from within the public bodies themselves. In 1982, for example, the Government launched its Financial Management Initiative (FMI) to improve the allocation, management and control of resources throughout central Government.

By the late 1980s the Government wanted to develop a more systematic approach to performance reporting across public bodies. This led to:

- An annual requirement on all newly created civil service executive agencies to report against Key Performance Indicators (from 1988 onwards).

- Similar measures being applied to all Non-Departmental Public Bodies (from the early 1990s).

- The creation of some 200 performance measures for Local Authorities to report annually on (from 1992).

- Similar requirements then being rolled out to include non-Local Authority services such as policing, primary and secondary education, further education and higher education.

In practice, by the end of the 1990s, most public bodies had some form of performance measurement and reporting in place. From the Output and Performance Analysis (OPA) applied to Government departments in the mid-1990s, to Public Service Agreements (PSAs) from 1998 onwards, all were intended to make decisions about spend and to see the results of spending. Alongside this, in 1991, a Citizens Charter was introduced which directly involved the public in the assessment of local services. This systematic approach also led to the establishment of audit and inspection bodies to set performance measures (e.g. Audit Commission) or analyse performance information (e.g. the National Audit Office).

Over time PSAs were reduced and the smaller number that remained became ‘cross cutting’ or ‘shared’ targets across different Departments. It was the Coalition Government that decided to abolish PSAs altogether, introducing Departmental Business Plans (DBPs) instead. DBPs were focused on service delivery processes and milestones rather than the previous focus on outcomes. In 2017 these became Single Departmental Plans (SDPs). SDPs were accompanied by Quarterly Data Summaries (QDS) providing snapshots of how each Department was spending its budget, the results it was achieving and how it was deploying its workforce. It was not possible nor intended for people to make direct comparisons between Departments from looking at QDSs. This is because different measures operated across Departments and their definitions and data collection processes varied.

Based on feedback from the National Audit Office (NAO), Public Accounts Committee (PAC), Institute for Government, Cabinet Office and HM Treasury; for the period 2019-2020, SDPs were improved in three key areas: (i) they were made more specific, (ii) they were more focussed on departmental priorities, and (iii) they included improved performance indicators.

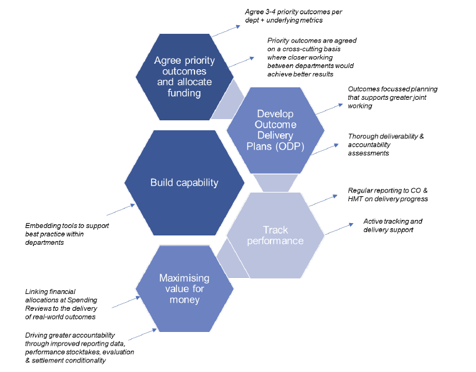

In March 2021, a joint letter was sent from the Cabinet Office and HM Treasury to the PAC. Following the one-year Spending Review [which set out Government Department’s budgets for 2021-2022] , the letter provided details about the development of a revised planning and performance framework. These new Outcome Delivery Plans (ODPs) will be focused on the delivery of priority outcomes and for strategic enabling activities. ODPs are intended to encourage better collaboration between Departments; lead to greater consideration of affordability, capability and risk; set new data standards and data-sharing requirements; and provide an ongoing picture of Departmental activity. Overall, ODPs are intended to assist Government improve its understanding of which interventions deliver the most meaningful outcomes and information from them will be used to inform future Spending Reviews. The letter contains a diagram setting out the new framework within which ODPs sit:

Why have targets?

In evidence submitted to the House of Commons Public Administration Select Committee back in 2003, the Government set out its rationale for setting what were then known as PSA targets, describing how:

“the targets…have proved immensely valuable by providing a clear statement of what the Government is trying to achieve. They set out the Government’s aims and priorities for improving public services and the specific results Government is aiming to deliver. Targets can also be used to set standards to achieve greater equity…The PSAs have contributed to a real shift in culture in Whitehall away from inputs and processes towards delivering outputs and results”.

PSA targets were viewed as a means of providing Departments with a clear sense of direction and ambition; getting them to focus on delivering results through requiring them to prepare delivery plans for each of their targets; provide a basis for monitoring what is and is not working; and to sharing this information with the public:

“Government is committed to regular public reporting of progress against targets. Targets are meant to be stretching so not all targets will be hit. But everyone can see what progress is being made”.

In the public sector, targets are intended to set out what central Government, Local Authorities and other public bodies want to do and by when. They then use this information to plan, monitor and report on the targets that they have set (or been set).

How are targets set?

Targets are often used when a particular problem or issue is identified which requires action. This involves looking at why the problem is happening, what is happening, how it is happening and who is being affected. In this context targets are intended to improve performance and behaviours.

Some national targets are mandated whilst others become recognised through their inclusion in procurement frameworks, quality or outcomes frameworks.

Sometimes targets are set between service providers and service users to reflect the outcomes that are important to people.

Some examples of national targets include:

- The Bank of England target of keeping inflation at 2%.

- The number of people waiting more than 4 hours in A&E and the number of people waiting over 18 weeks for non-urgent (but essential) hospital treatment.

- Deliver 300,000 net additional homes a year on average by the mid-2020s.

- Cutting emissions by 78% by 2035 compared to 1990 levels – and to reduce absolute carbon emissions by 34% 2020-2021 – achieving net zero by 2050.

- Public sector bodies with 250 or more staff in England to employ at least 2.3% of their staff as new apprentice starts over the period 1 April 2021 to 31 March 2022.

- At least 85% of UK premises to have access to gigabit-broadband by 2025.

It is important to note that targets are one means of charting progress against policy priorities. Not all public policy priorities or interventions lend themselves to a target.

What makes a ‘good’ target?

If we want to keep targets, how can we ensure they are clearly defined, understood and focused on addressing a policy issue or problem? For me, target design matters and this may include some or all of the following elements:

- Outcomes: a target(s) should focus on the real problem or issue [who is affected, how, why and the change you want to see] without being too prescriptive about how to tackle it.

- Do-ability: targets should focus on what a body or organisation can do rather than ideal outcomes.

- Realism: it may not be possible to eliminate a problem or issue, instead the target needs to be set to reduce the scale or severity of it.

- User voices: target setting should involve those with lived experience – including people who may be disengaged from ‘mainstream services’ and/or harder to reach.

- Measurability: targets should be able to be monitored and implemented.

- Flexibility: there needs to be some room for unprecedented situations without undermining the credibility of the target. Targets need some form of adaptation built in so as to respond to new circumstances.

- Scrutiny: a process of oversight and compliance should be in place to see how the target is being implemented.

- Deliverability: the body needs to be clear about what happens if a target is noy met – will there be incentives, a review process, or penalties? The target needs to be achievable rather than something that is consistently missed.

A good target can assist with prioritisation – it highlights to communities and businesses the importance of a problem or issue, and a commitment to do something about it. This can give the problem or issue momentum and can lead to actions and investments that might not otherwise happen.

What’s ‘wrong’ with targets?

In 2006, the NAO published the results of a survey of PSA data users. Whilst performance data was largely seen as clear and comprehensive; 25% of target owners said performance did not inform the management decisions they needed to take; 40% thought the data did not tell them what was wrong and almost 50% said it did not predict adequately what was likely to happen.

The survey results highlight how meeting targets can lead to some unintended consequences. For example:

- ‘Gaming the system’ to hit the target – particularly where incentives for their achievement are in place.

- Diverting resources from elsewhere to achieve a particular target – thus distorting other priorities leading to a concentration of resources in one area at the expense of other (non-targeted) areas.

- An increase in administration and bureaucracy which is disproportionate.

- Over-centralisation: national attempts to address a problem or issue often require locally coordinated responses.

- Gaps in data collection and the evidence base – whether or not a target is being achieved requires a common approach to definitions, data collection and analysis, and information sharing.

- Low cost – low commitment: targets can be seen as a means of appearing to take some action without having to fully commit to medium and longer-term decision making.

It is important to recognise how some of these unintended consequences may not result from the targets themselves but rather the way in which the targets were set and/or are being implemented.

How does targetry affect rural communities?

In June 2021, the Cabinet Office published a Declaration on Government Reform. This document sets out a commitment from Cabinet of Permanent Secretaries to a collective vision for building back better from COVID-19.

In July 2021, the Cabinet Office published ODPs setting out how each Department is working towards the delivery of its priority outcomes. Defra’s ODP 2021-2022 contains 4 policy priority outcomes:

- Improve the environment through cleaner air and water, minimised waster, and thriving plans and terrestrial and marine wildlife.

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase carbon storage in the agricultural, waste, peat and tree planting sectors to help deliver net zero.

- Reduce the likelihood and impact of flooding and coastal erosion on people, businesses, communities and the environment.

- Increase the sustainability, productivity and resilience of the agriculture, fishing, food and drink sectors, enhance biosecurity at the border and raise animal welfare standards.

The first two of these policy priorities are cross-cutting, involving joint work with other Departments.

Defra’s ODP contains a series of performance metrics, projects and programmes for each of these policy priorities. For example, the 4th policy priority [agriculture] contains the following performance metrics:

- Productivity of UK agricultural industry.

- Productivity of the UK food industry.

- Value of UK food and drink exported.

- Percentage of cattle herds that are now bovine tuberculosis free.

- Number of high priority forest pests in the UK plant Health Risk Register.

- Percentage of export health certificates and licences issued within agreed timescales.

A table for each performance metric sets out data from 2017-2018, where available, and then compares it to the latest update. The ODP also includes an additional metric that is new for 2021-2022 for which no historic data is available: ‘percentage of total allowable catches for quotas for fish stocks of UK interest that have been set consistent with maximum sustainable yield’.

To reinforce the ambitions set out in the Declaration on Government Reform, Defra’s ODP also focuses on 4 key enablers: (a) workforce, skills and location; (b) innovation, technology and data; (c) delivery, evaluation and collaboration; and (d) sustainability.

For me, I am interested in how the 4 priority policy outcomes can be used to set targets that deliver for rural communities. In setting performance metrics, who are these metrics for, how they will be measured, and how will rural communities benefit from their achievement? How can the development of a revised planning and performance framework and the development of ODPs across Government Departments improve opportunities for people to live and work in the countryside – for example, access to housing, broadband/mobile connectivity, transport, public services, health and care, education, employment, retail and leisure?

Some examples of other national ‘rural’ targets include:

- The Rural housing 5-star plan pledge to increase the current level of housing supply in rural communities by 6% per year.

- The Phase 3 Project Gigabit rollout programme intention to extend 1Gbps capable broadband ISP networks to a further 570,000 premises in rural and semi-rural areas.

- The Rural Payments Agency (RPA) has a number of key performance business indicators that it regularly reviews and updates. Some examples of these indicators include: at least 95% of applications for import and export licences processed within 5 working days; 95% of Rural Development Programme Scheme applications appraised within 60 calendar days – and 95% of claims processed within 30 calendar days; and 96% of notified cattle births, deaths and movements recorded within 5 working days of receipt.

On the one hand having nationally set policy priorities, targets and performance metrics can provide momentum, action, investment and visibility of rural issues. On the other hand, policy priorities and targets that are centrally determined can overlook the differences between urban and rural areas, and between different types of rural place [context]. What we should all be asking is do these measures help agencies achieve their goals – and how does this support rural communities and businesses?

Where next?

How can we balance those who think ‘targetry’ should be limited, reduced or scrapped altogether, with those who want more? For me, this involves answering the following questions:

- Where does the target come from and how has it been designed? For example, is it based on need, robust data and analysis?

- Is the target realistic and there to be hit? It has almost become commonplace in some public service areas to miss targets.

- Is the target measurable – and what data or set of figures or metrics are being used to monitor the achievement of/towards it?

- How can we avoid or mitigate unintended consequences?

- Does it account for any external or systematic factors that may affect their deliverability?

- Ultimately, how will it help us achieve our goals?

- And if won’t help us achieve goals and/or you don’t want targets – and some policy areas do not lend themselves easily to target setting – what alternatives are there that we can use instead?

When set well targets can improve the performance of public services. Yet the very act of being given a target often changes human behaviour. If we are going to continue to use targets we need to ensure they focus on addressing a problem or issue, are well considered, and centred on delivering the outcomes we want to see. For rural communities this means being more specific about how policy priorities, targets and performance management will enable more people to live and work in the countryside.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

Jessica is a researcher/project manager at Rose Regeneration and a senior research fellow at The National Centre for Rural Health and Care (NCRHC). Her current work includes supporting health commissioners and providers to measure their response to COVID-19 and with future planning; and evaluating two employability programmes helping people furthest from the labour market. Jessica also sits on the board of a Housing Association that supports older and vulnerable people.

She can be contacted by email jessica.sellick@roseregeneration.co.uk.

Website: http://roseregeneration.co.uk/https://www.ncrhc.org/

Blog: http://ruralwords.co.uk/

Twitter: @RoseRegen