Are rural residents ‘retirement-ready’?

Although the idea of offering a State Pension was first proposed in the eighteenth century it was not until the Government established two committees in the 1890s (the Rothschild Committee on Old Age Pensions in 1896 and a Select Committee on the Aged Deserving Poor in 1899) that the matter was fully explored. This led to the Old Age Pensions Act 1908 which resulted in the Government providing 5 shillings to those over 70 who had an income of less than 10 shillings a week. The first pension system was therefore a means of averting poverty in older age. Since then successive Governments have made many changes to pension provision – resulting in a system today which is both complex and multi-layered. What does the current pension landscape look like and what might future reforms mean? Jessica Sellick investigates.

………………………………………………………………………………………………..

What is a pension? A pension is a form of income you can use in later life. The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is responsible for ‘providing a decent income for people of pension age and promoting saving for retirement’. DWP provides pensions, benefits and retirement information for current and future older people in the UK and abroad. The services they currently deliver include State Pension and Pension Credit, as well as Winter Fuel Payments, Cold Weather Payments, Carer’s Allowance, Attendance Allowance and Visiting Service. In 2018-2019 DWP spent some £182.5 billion on benefit payments from its Annually Managed Expenditure (AME) – with the majority of these payments, £101.1 billion, to older people. Of the £110.1 billion – £96.6 billion was spent on State Pension, £5.6 billion on Housing Benefit, £5.1 billion on Pension Credit, £2 billion on Winter Fuel Payments and £0.8 billion on other benefits (e.g. free TV licences for the over 75s).

Today there are several different types of pension schemes available to help people save money for their future. These schemes vary according to an individual’s circumstances – including how much they have or want to pay into them, and in how they operate. The amount an individual receives is dependent upon how much money they have contributed into their pension pot during their working life.

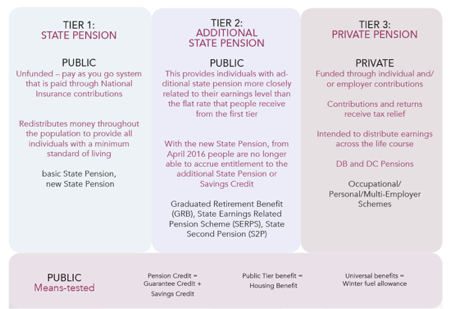

What is the pensions system in the UK like? According to The Pensions Policy Institute (PPI), the UK pension system has three tiers:

- Tier 1 is provided by the state and consists of a basic level of pension to which almost everyone either contributes or has access. This provides every citizen with a minimum level of retirement income.

- Tier 2 is also administered by the state and aims to provide pension income that is more closely related to employees’ earnings levels. Tier 2 is less redistributive (from higher-income to lower income) than Tier 1. Tier 1 and Tier 2 operate on a ‘pay-as-you-go’ contributory basis, through the National Insurance (NI) system.

- Tier 3 is voluntary (private) pension arrangements that are not directly funded by the state. Private pension contributions can come from employers and/or employees and funds provide designated pensions for the individual. The primary aim of private pensions is to redistribute income across an individual’s lifetime, and not to redistribute income from higher-income to lower-income people. Tier 3 includes pensions arising from automatic enrolment, a policy requiring employers to enrol eligible employees into a qualifying workplace pension scheme.

These tiers are summarised in the diagram below:

For tier 1, State Pension entitlement is based on an individual’s NI contribution record. Any tax year in which an individual makes, or is credited with making, sufficient NI contributions is known as a qualifying year. There are 27 activities that can credit someone into the State Pension without them having to pay contributions (e.g. if an individual is receiving Statutory Sick Pay, Statutory Paternity or Adoption Pay, Carers Allowance, Jobseeker’s Allowance or Employment and Support Allowance). People can also make voluntary contributions to fill gaps in their contribution record. For people applying for State Pension on or after 6 April 2016, thirty-five years of NI contributions are necessary to qualify for a full State Pension – with a minimum of ten qualifying years necessary to get any new State Pension.

The Pensions Act 2014 includes a review of the State Pension Age (SPA) at least once every 5 years and is underpinned by an assumption that people should expect to spend a third or less of their adult life in retirement; where adult life is defined as starting at aged 20 years. The SPA – the minimum legal age at which State Pension can be claimed – has been increasing incrementally from age 65 to reach age 66 in October 2020. The SPA was scheduled to increase to 67 years between 2034 and 2036 and to 68 years between 2044 and 2046. However, Government brought forward the rise to age 67 years to take place between 2026 and 2028. In March 2017 the Independent State Pension Age Review was published. The Review recommended that the SPA increase to 68 years over a two-year period starting in 2037 and ending in 2039, to reflect changes in life expectancy.

There are three strands to tier 2 provision, which like tier 1 is also provided by the state: (i) Graduated Retirement Benefit; (ii) State Earnings Related Pension Schemes; and (iii) Second State Pension. These schemes are historic and people have not been able to build up entitlement for an Additional State Pension since 2016.

The third tier of provision is private pensions, including workplace pensions and individual pension schemes. These are not directly funded by the state. These schemes tend to be Defined Benefit (DB) or Defined Contribution (DC). With DB, contributions are varied in order to ensure that the level of promised benefits is reached; whereas with DC contributions are usually expressed as a percentage of salary or total earnings [where the DC could be a flat rate or tiered by age or length of service]. The Pensions Schemes Act 2015 introduced legislation to facilitate shared risk and collective benefit schemes and are based on the level or amount of pension benefits, with elements of DB, DC and/or Collective Defined Contribution (CDC) schemes.

Automatic Enrolment (AR) has resulted in more employees joining pension schemes. Employees aged between 22 years and SPA are eligible for automatic enrolment into a scheme chosen by their employer, with employees having the right to opt-out. AR began in October 2012 when larger employers (with 250+ employees) were required to auto-enrol eligible employees between October 2012 and February 2014. Medium employers (those with 50-249 employees) were required to auto-enrol eligible employees between April 2014 and April 2015 and small employers (those with fewer than 50 employees) to do so between June 2015 and April 2017. For employees who opt in to AR a minimum of 8% of their band earnings must be paid in – of this 3% is contributed by the employer and 5% is paid in by the employee. Employees have the right to opt out – and must revisit their decision every 3 years. A review of AR published by DWP in December 2017 made a number of recommendations from the mid-2020s including removing the lower limit on the salary for contributions [currently £10,000]; reducing the minimum age from 22 years to 18 years; and finding new ways to improve pension saving for self-employed people.

How much state pension do people receive? Between 1974 and 1979 the State Pension (tier 1) was increased annually by the greater of the increase in National Average Earnings (NAE) or the increase in the Retail Prices Index (RPI). Since 1979 annual increases have generally been linked to RPI. While the value of the State Pension increased in real terms, when compared to NAE its value has actually declined since 1979. From April 2011 State Pension has been uprated by the higher of the increase in earnings (Consumer Prices Index, CPI) or 2.5%. The full new State Pension is currently £168.60 per week – with the actual amount dependent upon your National Insurance record.

Are we paying ‘enough’ into our pensions? According to HM Revenue & Customs, £28.2 billion was contributed to personal pensions in 2017-2018; with the total value of contributions rising from £27.4 billion in 2016-2017. While the number of individuals contributing to a personal pension increased – from 9.4 million in 2016-2017 to 10.4 million in 2017-2018 [part of a sustained increase attributed to the introduction of AR in 2012]; the annual average contribution per individual has fallen – from £2,900 in 2016-2017 to £2,700 in 2017-2018. Annual average contributions per individual grew between 2006 and 2012 (peaking at £3,690 per individual). Gross pension tax relief for 2017-2018 is projected to be £37.8 billion, up from £37.1 billion in 2016-2017. Tax on private pensions has also increased, from £17.8 billion in 2016-2017 to £18.3 billion in 2017-2018. This data reveals how the net cost of pension tax relief is increasing. Indeed, over the past five years pension tax relief has increased by 30%.

As the pension system has become increasingly expensive commentators have discussed a need to reform the existing structure in order to control costs and free up cash for Government to use to deliver public services. It has also opened up debate on who benefits most from the current system – with opponents suggesting the current system favours wealthy individuals as higher rate taxpayers gain the biggest tax relief on contributions and proponents pointing out how some high earners have spent years on low incomes with little spare household income – and now they are earning more they are prohibited from saving more than £10,000 a year into a pension even though their time earning a higher income may be a small part of their overall working life.

Numerous studies have suggested millions of us are not saving enough to give us the standard of living we are hoping for when we retire. A survey in 2019 carried out by Willis Owen found just over one-third of women do not have a pension plan compared to 17% of men. Of the female respondents, 17% said they had no intention of saving into a pension scheme until they reach 40 years, and 9% intended to delay saving into a pension until they are at least 50. In the same survey 35% of respondents said they had stopped paying into a pension scheme during the past year citing how they were no longer afford to make contributions.

A survey of 1,500 millennials (25-35 year olds) from Royal London reveals how the amounts young people are saving towards their pension are less than 5% of their income (an average of 4.6%). This is below the level of pension contribution Royal London recommends (which is 12-15% of your income) to help achieve a reasonable income amount in retirement.

Figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show that 4.2 million self-employed workers are not saving into a pension scheme. At the same time the number of people estimated to be self-employed has increased by 162,000 a year to almost 5 million.

What is clear from many of these surveys is that some people need money for now to meet their financial responsibilities – from trying to get on the property ladder, through to paying for education and caring responsibilities. Indeed, many of us are putting off paying into a pension because the amount we can afford to pay in is deemed too small to be worthwhile; or because these savings are inaccessible until we retire.

On the other hand, some older people already have enough to live on – either because they carry on working or have other income to live on – leading them to delay accessing their pension pot beyond their selected retirement date or their pension scheme’s normal retirement date. A Freedom of Information request (FOI) submitted by Canada Life revealed not only how more than 14,000 opted to stop receiving their State Pension (tier 1) in the 2018-2019 tax year, but also how people can only opt to suspend and re-start their pension on one occasion after it is in payment. Andrew Tully from Canada Life explained how “This [opting not to receive State Pension] could be for a number of reasons, most likely is the simple fact they didn’t need the income and were looking to manage their tax liability, either because they returned to work or continued in paid work, or possibly because they received an inheritance. This sort of flexibility is common in the private pension sector, where people are able to turn income on and off from pensions using the right products, but is not a well understood part of the State Pension system.”

To help you consider how much you should be saving into a pension, the Money Advice Service has a pension calculator. This works out your SPA and State Pension income amount, asks you about the amount of income you’d like in retirement, looks at your current contributions and other sources of income and identifies any shortfall and suggests ways to improve this. The Money and Pensions Service is delivering a pensions dashboards programme which, in the future, will enable people to see all their lifetime pension savings in one place. The programme is currently working on designing, testing and building a consumer facing dashboard.

For me, whether or not we are paying enough into our pensions highlights four issues:

- We are living longer, some of us will want to continue working full-time or part-time or begin a new career, some of us may retire early because of health issues; some of us may face redundancy and struggle to find another job.

- When we retire some of us may want to increase our spending (e.g. to travel or start a new hobby) while others of us will want to reduce our spending (e.g. moving to a smaller property).

- For some RSN readers retirement feels some way in the distance and you have more pressing financial goals (mortgage, saving for your children’s education).

- Some of us are not sure how pensions work and that the benefits of saving sooner could mean a larger pension pot when we eventually retire.

All of this makes it difficult to identify how much money we need to save for retirement let alone coming up with an actual plan to do it!

Are people living in rural areas paying enough into their pension pot(s)? According to Defra’s Statistical Digest of Rural England:

- Rural areas have a higher proportion of older people compared with urban areas. In 2018, the peak age group in rural areas was 50-54 years (8% of the rural population), while the peak age group in urban areas was 25- 29 years (comprising 7.3% of the urban population).

- The percentage of people living in relative and absolute low income is lower in rural areas than in urban areas. The percentage of working-age people in rural areas in relative low income was 13% before housing costs and 16% after housing costs. In comparison, the percentage of working-age people in urban areas in relative low income was 15% before housing costs and 21% after housing costs. The percentage of pensioners in rural areas in relative low income was 17% before housing costs, and 14% after housing costs. In comparison, the percentage of pensioners in urban areas in relative low income was 19% before housing costs and 18% after housing costs. The dashboard shows that in rural areas, between 2016-2017 and 2017-2018, relative income for children, working-age people and pensioners increased; and absolute low income for working-age people and children also increased before housing costs. These figures reveal how many thousands of people living in rural areas are in households below average income (HBAI) and how these numbers may be increasing.

- In 2018 there were 1,031,000 home workers in rural areas, accounting for 21% of all workers living in rural areas. This compares to 31% of all workers living in urban areas (some 2,888,000 home workers). Home workers are defined as those who usually spend at least half of their work time using their home, either within their grounds or in different places or using it as a base. Home workers will include both those who are employees of organisations and those who are self-employed.

- In 2018 median workplace earning in predominantly urban areas (excluding London) were £23,300 – for predominantly rural areas this figure was lower at £21,900. In 2018 median residence-based earning in predominantly urban areas (excluding London) were £23,500 and slightly higher in rural areas at £23,700. Average residence based earnings differ from workplace based earnings because people living in rural areas sometimes work in urban areas in higher paid jobs.

Researchers in the United States looked at how working age residents in Michigan’s rural Upper Peninsula were engaging in retirement planning. The researchers found rural residents were less likely to make maximum contributions compared to their urban counterparts – which they attributed to rural areas having smaller populations, lower medium incomes, higher unemployment rates, and seasonal and short term work. The researchers called for easier retirement plan participation and public service campaigns to notify individuals of the tax and personal advantages.

In comparison, work in the UK has tended to focus on looking at people growing old in or retiring into rural communities – from housing and access to services, to transport, health and care and community activities – rather than focused on when, why and how much they are saving for their retirement. In low-income households, and those living and working in rural areas (including self-employed), how much are they contributing into a pension and saving for their retirement?

For those who have retired or are looking to retire figures from the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and The Pensions Regulator (TPR) suggest that 42% of pension savers, equating to some 5 million people, could be at risk of falling victim to pension scammers. The likelihood of being drawn into one of more scams increased to 60% among those who said they were actively looking for ways to boost their retirement income. The FCA and TPR believe pension cold-calls, free pension reviews, claims of guaranteed high returns, exotic investments, time-limited offers and early access to cash before the age of 55 years could all tempt savers into risking their retirement income.

While the principal focus of this briefing has been on the pension arrangements of individuals, there has been much discussion around the deficits of some schemes: this is the gap between how much a pension is required to pay out versus how much money is available to pay out and occurs when there isn’t enough money to pay. For example, in February 2020 BAE systems agreed a deficit recovery plan with The Pensions Regulator after a valuation revealed a deficit of £1.9 billion. At the same time, analysis of Councils in London found a combined total pension deficit of £17.98 billion for the period 2018-2019, representing a 7% rise on the previous 12-months. According to analysts, the situation has been exacerbated by legal rulings against the Government including the McCloud case, relating to the shift from final salary schemes to less generous pension arrangements based on average salaries. The Government announced a pause to the cost control part of the valuations of public service pension schemes and has estimated that the ruling could add up to £4 billion a year to the cost of funding public sector pensions.

RSN readers will be aware that sometimes changes to pension arrangements have unforeseen consequences. According to research from UCU a typical member of the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS) will pay £40,000 more into their pension pot but receive £200,000 less in retirement. In the NHS, for example, we have seen how fewer clinical and non-clinical staff are seeking promotion, taking on leadership roles or doing additional shifts as a result of pension taxation rules – while Government announced an interim solution for clinical staff in December 2019 this does not apply to non-clinical staff.

Many of us want to save enough money to be able to retire but struggle to understand what, when and how we can become ‘retirement-ready’. For people in rural areas this has particular implications around job security, wage levels, housing and living costs and access to services (e.g. transport, care). The next independent pension review is due in 2022 – what should our ‘rural asks’ be?

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

Jessica is a researcher/project manager at Rose Regeneration. Her current work includes helping public sector bodies to measure social value; evaluating an employability programme; and reviewing a project that supports parents committed to recovering from drug and/or alcohol addictions. She is also a senior research fellow at The National Centre for Rural Health and Care (NCRHC).

She can be contacted by email jessica.sellick@roseregeneration.co.uk or telephone 01522 521211. Website: http://roseregeneration.co.uk/https://www.ncrhc.org/ Blog: http://ruralwords.co.uk/ Twitter: @RoseRegen