What are the implications of COVID-19 and Brexit for the post-millennial generation?

New research published by The National Federation of Young Farmers’ Clubs (NFYFC) reveals how young people are pessimistic about future opportunities to live and work in rural areas and believe the pandemic will continue to affect their prospects in the long-term. What needs to be done to support young people, now and in the years ahead, to ensure they can have a stake in the countryside? Jessica Sellick investigates.

………………………………………………………………………………………………..

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) states that a child ‘means every human being below the age of eighteen years unless, under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier’. In England, The Children Act 1989, makes a number of orders relating to the welfare of children, defining a child (under Section 105) as ‘a person under the age of 18’. Prior to that, back in 1933 the Children and Young Persons Act imposed criminal liability for the abandonment, neglect or ill-treatment of any child under 16 years of age by anyone over 16 years of age.

In practice, there is no one understanding of children and/or young people shared by all agencies and bodies; and no set time or age in which a child necessarily moves to becoming a young adult and through to adulthood.

In medicine, for example, the terms ‘children’ and ‘young people’ are used from birth until their 18th birthday – with the word children used to refer to younger children “who do not have the maturity and understanding to make important decisions for themselves” and young people to refer to “older or more experienced children who are more likely to be able to make these decisions for themselves”. There is no specific age at which children’s services within the health system end, although generally children requiring continuing treatment transition to adult services between the ages of 16 and 18 years, depending on the service area, local factors and the individual.

In education, a child can leave school on the last Friday of June if they will be aged 16 years by the end of the summer holidays – but they must stay in full-time education, start an apprenticeship or traineeship, or spend 20 hours a week or more working or volunteering while in part-time education or training.

From aged 14 years a child can obtain a part time job involving ‘light work’ with some restrictions set over the number of hours and when the work can take place. A young adult can leave home without parental consent at the age of 18 years – although there are provisions contained within the Children’s Act for exceptional circumstances relating to residence coming to an end before or at aged 16 years.

If a child has been ‘looked after’ by the Local Authority they are provided with a needs assessment and a pathway plan for leaving care that can finish when they are aged 21 years. For those children that go on to higher education, the Local Authority has a duty to assist them past the age of 21, to the extent that his or her welfare and educational and training needs requires it.

A 17-year old can obtain a licence to drive a car, small goods vehicle and an agricultural tractor on the road but not a medium or heavy goods vehicle (where they need to be 18 years old) or large passenger vehicle (where they need to reach 21 years of age).

These definitions are important – on the one hand illustrating how we make special protection and provision to children (sometimes while they are under or until they reach 16 years of age, 18 years of age, or beyond 18 years under some circumstances); on the other hand children and young people are often regarded as adults able to make and be responsible for their own decisions (e.g. driving, employment). Crucially, some of these definitions determine what support a child/young person is entitled to receive and from whom and when.

Age is also important as it is one of the predictors of differences in attitudes and behaviours. ‘Generations’ are one means researchers use to group age cohorts; with each cohort typically spanning people born over a 15-20-year time period. The Pew Research Center, for example, defines younger cohorts as Millennials (anyone born between 1981 and 1996 and aged 24-39 years in 2020) and ‘post millennials’ or Generation Z (people born between 1997 and 2012, currently aged 8-23 years in 2020). Generational cohorts provide a means for researchers to explore how different formative experiences (e.g. pandemics, recessions) interact with the life cycle and shape their view of the world over the longer-term. For example, the Centre for Longitudinal Studies at University College London has been undertaking a National Child Development Study since 1958, with cohort members followed up ten times since the study began, with the next sweep due to take place in 2020 – 2021 when the participants will be in their early sixties. The Centre is using participants from this study and four other studies to carry out a national longitudinal study on COVID-19. Similarly, Generation Scotland, based at the University of Edinburgh, is carrying out a RuralCovidLife survey to better understand how COVID-19 measures are affecting the health and wellbeing of people in rural Scottish communities – the survey complements a longitudinal health and wellbeing study involving 7,000 families since 2006.

Engaging and empowering young people through research is important – for it reveals important insights about their influences, aspirations and outcomes as they move through childhood and adulthood. It also provides an evidence base to guide policy makers – providing them with valuable data on a range of issues, their causes, and the effectiveness of different interventions.

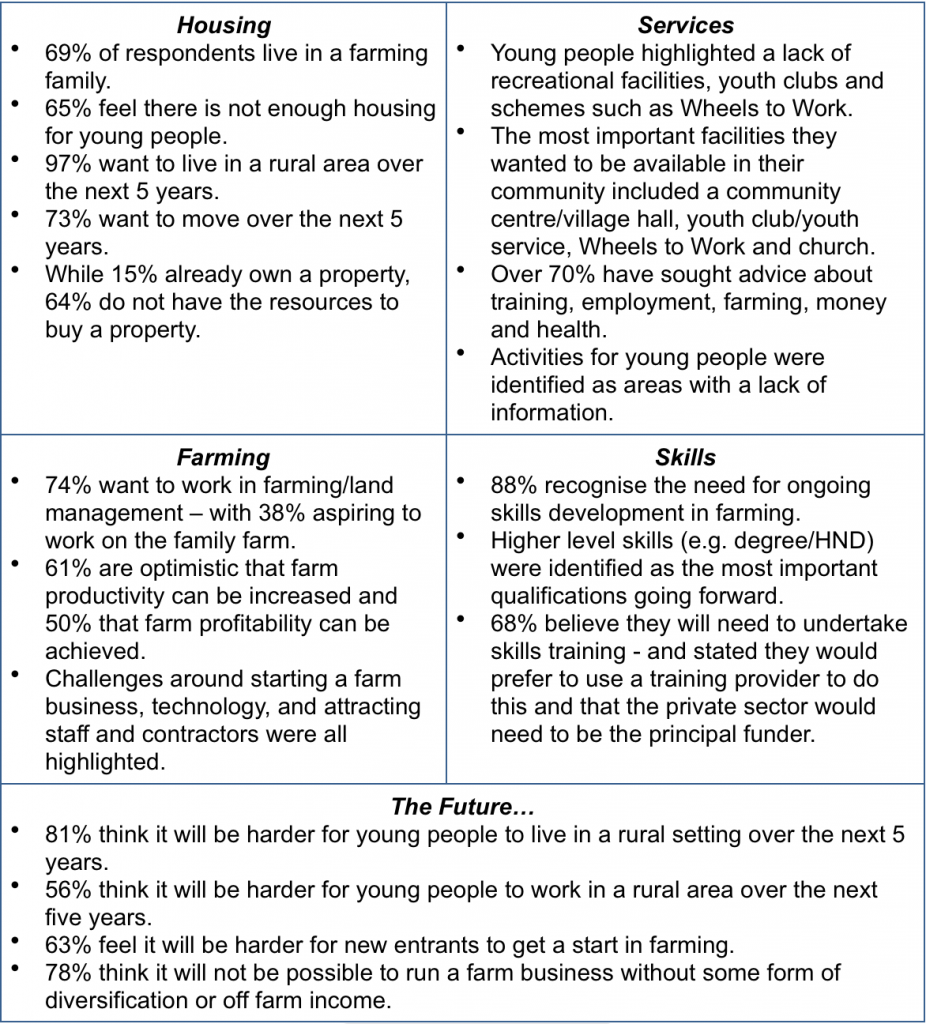

What do post millennial young people think about growing up in the countryside? In June 2020, the National Federation of Young Farmers’ Clubs (NFYFC) launched a survey, ‘Your Post-Brexit Rural Future’. Funded by Defra and led by the NFYFC and Rose Regeneration, the survey provided young people living and working in rural areas, next generation farmers and land managers with an opportunity to share their views on living and working in the countryside, now and into the future. Input to the survey questions was kindly provided by English Rural, AHDB, and the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT). 528 young people responded to the survey, offering their views on housing, services, farming, skills, COVID-19 and the future.

To build on the survey findings Rose Regeneration carried out 40 follow-up telephone interviews with young farmers. During the lockdown period March-June 2020, young farmers highlighted the impact of COVID-19 on their farm businesses; with some indicating how they had struggled to recruit and/or retain workers, received no income or reduced income from farm diversification activities (e.g. closure of café/restaurant, holiday lets, wedding venue), had been unable to undertake agricultural training, had been pushed to meet changing supermarket and consumer demands, and had to respond to more people walking in the countryside and not closing gates or keeping to designated footpaths. Young farmers also discussed the closure of some auction marts and the cancellation of agricultural shows which provide important outlets for them to meet each other and connect directly with the public.

Young farmers provided some examples of how they have adapted to COVID-19 and mitigated some of its effects. These included: creating ‘farming bubbles’ by keeping the same staff together on shifts to work as a protective measure to help reduce the potential risk of transmission – and providing personal protective equipment (PPE) and ensuring social distancing. Other on-farm examples included ensuring vehicles are not shared by staff – and ensuring vehicle cleaning before and after each journey; increasing online and/or direct sales to consumers (e.g. farm shop, box schemes, roadside sales); piloting new diversification ideas (e.g. pick-your-own, mazes); and purchasing equipment and supplies online rather than visiting premises. Some farm businesses had furloughed staff involved in non-agricultural activities (e.g. hospitality, weddings/events). Young farmers were considering their options in recovering from COVID-19 which varied from looking to increase online sales through to pop up visitor facilities and attractions (e.g. café, food stand, outdoor/countryside classroom), farm stays [converting agricultural buildings into visitor accommodation] and accessing online training opportunities.

During the lockdown period March-June 2020 Young Farmer Clubs used social media and provided support online/virtually so they could carry on with regular activities that could not happen face-to-face (e.g. meetings, event planning, competitions, rallies); raise awareness and run campaigns (e.g. mental health support, buy local-buy British); and deliver new social activities (e.g. stock judging, bale sculptures, virtual farm tours).

The financial implications of COVID-19 on clubs were emphasised during many of the telephone discussions. These concerns covered three main areas: (1) the impact of a second peak/wave on the next financial year if social distancing measures are still in place or reintroduced; (2) members – particularly newer members – may not renew their membership if clubs are unable to offer regular face-to-face activities; and (3) Clubs may be unable to generate a surplus and donate money to local or national charities. While many young farmers described how they had benefitted from accessing their club through digital platforms; other members miss face-to-face activities and have struggled to engage with the virtual offer. In some instances, club Chairs made telephone calls to members and/or socially distanced visits. Since lockdown restrictions were eased from July 2020 in some areas, clubs have been trying to balancing online/virtual with restarting some face-to-face activities (in line with Government guidelines).

During COVID-19 Government identified farmers, farm workers and people in the food supply chain as ‘key workers.’ Young farmers suggested this had led the public to recognise the work they do in supplying the nation’s food: “farmers are key workers, but I don’t think a lot of recognition was given to farmers before COVID-19.” The majority of interviewees perceived COVID-19 as a short-term problem – with farming facing other threats/issues that have been neglected during the pandemic. These issues can be grouped into three themes: (i) Brexit – and the transition to a new Agricultural System; (ii) broadband and mobile connectivity; and (iii) climate change and the environment. Young people are thinking about the future and the implications of this bigger picture on their farm business, skills and future work: “young farmers are resilient, and innovative, and that’s why we’ll make the best of the situation.”

Overall, the findings of the research suggest:

1. Young people want to have a stake in the countryside: they care about the community where they live and many take an active part in local organisations and activities (e.g. church, parish council, school, pub). Often growing up and spending many hours working on a farm means they already have a wealth of skills and experiences at a young age compared to their peers not growing up on a farm.

2. Young people are a vital part of the social fabric of rural communities: this has become even more apparent during COVID-19 with many young farmers delivering medicines or groceries and phoning or visiting vulnerable residents for example.

3…But they are pessimistic about the future: while many young people want to continue to live and work in the countryside, this research suggests they will only be able to do so if they remain on their family farm. Similarly, many young farmers believe that if they are to have a future in farming, they will need an off-farm income to supplement and sustain them.

4. COVID-19 restrictions have had a big impact on young farmers and clubs: not being able to meet face-to-face and socialise has had a significant effect on the health and wellbeing of young farmers. Clubs are taking stock in looking at how they deliver activities virtually and in person and the support they need to do this.

5. Young people are seeking information and advice – and some want more…they are more likely to talk about their mental health than their parents or grandparents. They want more information on housing and activities available for young people. Given the need to undertake further training and skills development [particularly higher-level courses/qualifications] accessing this information will also become increasingly important.

6. Policy and decision makers need to ensure the voices of young farmers are heard: as future farming schemes are developed and introduced, listening and responding to feedback from young farmers will continue to be important. Defra also has a strategic role as rural champion across Government and can ensure some of the themes emerging from the research (e.g. housing, youth services and activities) are picked up by other relevant Government departments.

These findings were discussed at a special panel debate held during National Young Farmers’ Week 2020. This current research and discussion builds on a survey carried out by the NFYFC in 2016 which sought to gather the ideas of young farmers for a future British Agricultural Policy. The findings covered six areas: negotiating a better deal for young farmers; future farm business culture; employment skills and training; farming regulations; building farm businesses; and farming subsidies. When asked ‘which do you feel it is most important for UK Government negotiators & legislators to focus on, and which do you feel it is most important for farming’s industry bodies to focus on?’, 79% of the 184 respondents stated that the UK Government should focus on controlling the costs of production and 78% stated that farming industry bodies should focus on consumer confidence. The survey found the two biggest barriers for young farmers wanting to start in or to remain in farming were around access to land and access to credit.

Amid COVID-19 and Brexit these are uncertain times for children and young people wanting to live, grow up, learn, work and spend time in the countryside. On the one hand, there can be particular challenges for young farmers, particularly relating to the time they may have to wait before they have the chance to farm in their own right (e.g. access to land, finance, succession planning), juggling paid work on the farms of others or off-farm, and balancing the demands of studying or training with paid work. On the other hand, their involvedness in farming, sometimes from a very early age, and their passion, means they already have a wealth of skills, knowledge and maturity not always seen in other cohorts of young people in the general population. With many longitudinal studies underway, what might research with young farmers tell us about the effectiveness of policy and industry interventions designed to support the industry post Brexit, and how to make a success of farming as a career? Watch this space.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

Jessica is a researcher/project manager at Rose Regeneration and a senior research fellow at The National Centre for Rural Health and Care (NCRHC). Her current work includes supporting health commissioners and providers to measure their response to COVID-19 and with future planning; working with 8 farm support groups across England on a Defra funded resilience programme; and helping 3 places to develop proposals for a Town Deal. Jessica also sits on the board of a Housing Association that supports older and vulnerable people.

She can be contacted by email jessica.sellick@roseregeneration.co.uk.

Website: http://roseregeneration.co.uk/ https://www.ncrhc.org/

Blog: http://ruralwords.co.uk/

Twitter: @RoseRegen