Building a long-term vision for the countryside – what can we take from #Rural2040?

On 30 June 2021, the European Commission published a long-term vision for rural areas. What does the vision contain, will it help rural communities and businesses reach their full potential in the coming decades, and will it raise the profile of the countryside amongst policy makers? Jessica Sellick investigates.

Under the strapline of ‘a vibrant tapestry of life and landscapes, Europe’s rural areas provide us with our food, homes, jobs, and essential ecosystem services’, the European Commission recently published a long-term vision for the EU’s rural areas up to 2040. Why and how has the European Commission developed this vision, what does it contain, how will it be implemented, and what can rural areas outside of the EU take from it?

Why develop a vision?

In 2018, rural areas represented 83% of the total EU areas and were home to 30.6% of the EU’s population. Rural areas in the EU are defined by a wide range of social, economic and environmental qualities:

- The percentage of the population at risk of poverty and social exclusion is higher in rural areas than in towns and cities.

- In cities, the average road distance to the nearest doctor is 3.5km whilst for remote rural areas the average distance is some 21.5km.

- 60% of households in rural areas have access to fast broadband compared to 86% of the EU population as a whole.

- Since 2012, the employment rate in rural areas for people aged 20-64 years has increased across the EU from 68% to 73%. However, the total number of employed persons has not increased, suggesting that the increase in the employment rate is due to the decrease of the active population.

- In 2018, the average GDP per capita in rural regions was only three quarters of the EU average.

- In 2018 and 2019, 50% of rural residents tended to trust the EU compared to 55% of the city residents, while only 37% of rural residents tended to trust their national government (compared to 41% in cities). Rural residents are more likely to trust local and regional authorities (57%) than their national government or the EU.

- Rural residents were more likely to participate in formal and informal voluntary activities (20% and 24% respectively) compared to urban residents (17% formal and 22% informal).

While some rural areas are the most prosperous and well performing in their countries, others are experiencing demographic ageing, depopulation and poverty. These figures illuminate some of the opportunities and challenges facing Europe’s rural areas – including territorial governance, social sustainability, community health and wellbeing and infrastructure development. The vision has therefore been developed to address regional and territorial disparities between rural areas which have continued to persist.

According to the Communication issued by the European Commission, the long-term vision is intended to build upon ‘the emerging opportunities of the EU’s green and digital transitions and the lessons learnt from the COVID-19 pandemic’ and identify ‘the means to improve rural quality of life, achieve balanced territorial development and stimulate economic growth in rural areas’.

To develop the vision, a foresight exercise ‘EU Rural Areas 2040’ took place in 2020 to develop future scenarios describing different pathways towards 2040. Four scenarios were produced in collaboration with the European Network Rural Development (ENRD) thematic group on Long Term Rural Vision:

- Rurbanities scenario – people turn to rural areas looking for a higher quality of life. Rural communities subsequently benefit from a diversity of economic activities and job opportunities. However, there is limited coordination between different governance levels, little sense for ‘local community’ and a ‘not-in-my-backyard’ attitude contributing to tensions between residents and policy-makers.

- Rural renewal scenario – increasing numbers of people move to rural areas wanting more sustainable living. Nature-based solutions, circular economy and sustainable pathways have been implemented and there is a conscious effort in building and maintaining communities.

- Rural connections scenario – as population numbers and economic activity decline in rural areas it becomes increasingly difficult to maintain smaller villages, so people start to concentrate around rural hubs. To manage this transition, priority is given to digital infrastructure to facilitate connection and networking, e-services (e.g. health, education), and agriculture (e.g. precision farming, automation).

- Rural specialisation scenario – most people have moved to urban centres due to lower economic and social opportunities and minimal public support in rural areas. Land management is left in the hands of a few actors, resulting in large-scale automated facilities (e.g. farms, renewable energy installations).

These scenarios were tested through a series of participatory workshops. These sessions also took account of internal and external factors that could cause change, including multilevel governance: the extent to which actors coordinate, collaborate and make collective decisions; and demography: the extent to which the rural population increases due to in-migration from urban centres [expansion], or decreases due to out-migration to urban centres and an ageing population [shrinkage]. Workshop attendees also considered other issues in the sessions such as environmental drivers (e.g. climate change and availability and quality of natural resources); socio-economic drivers (e.g. sense of community, availability and access to services, globalisation); technological drivers (e.g. digitalisation, new mobility); and drivers related to land use and the future of the agricultural sector.

Some general observations emerged from this foresight work:

- All of the scenarios place an emphasis on the central role that digital infrastructure and services have for future activities in rural places.

- While rural areas will continue to play an essential role for food, energy, environmental services/protection and leisure; the social importance of rural areas differs depending on demographic developments.

- Whether the population increases or decreases in rural places, this change needs to be carefully managed – with active community building needed to integrate a more diverse rural population.

- Land use management will require more attention as climate change mitigation and adaptation become more important – from tackling rural sprawl through to the abandonment of land.

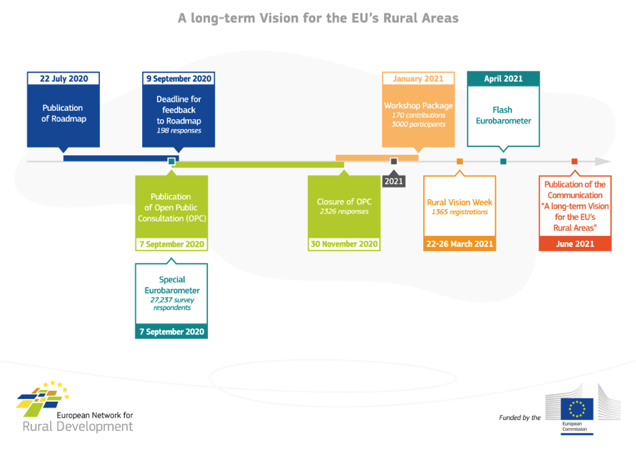

In addition to this visioning work, the ENRD undertook an extensive consultation which is summarised in the diagram below:

Between September and November 2020, the European Commission ran a public consultation on the vision. 2,326 responses were received with the analysis finding:

- More than 50% of respondents stated that infrastructure is the most pressing need for rural areas, specifically in terms of establishing a better public transport system.

- More than two-thirds of respondents (67%) indicated that ‘quality job opportunities’ are not sufficiently available for people living in rural areas (52% rarely available and 15% unavailable).

- The two most important reasons for deciding to live in a rural area were ‘better quality of life’ (72% very important and 22% important) and ‘less polluted environment, less heat stress, proximity to nature’ (75% very important and 20% important).

- ‘Farming/agriculture’ is perceived as the most important sector by 93% of the respondents (74% rated it as very important and 19% as important). ‘The agri-food sector (including processing of primary products)’ is considered the second most important sector (61% viewed it as very important and 29% as important).

- Respondents suggested the attractiveness of rural areas in 20 years’ time depends on the availability of digital connectivity and basic services/E-services: 93% of the replies highlighted digital connectivity (71% much more attractive and 22% more attractive) and 94% basic services/E-services (69% much more attractive and 25% attractive).

- The reduction of the impact of farming on climate and environment was also seen as influencing the attractiveness of rural areas for 92% of the respondents (with 66% stating this would make a rural area much more attractive and 26% more attractive).

In early 2021, the ERND thematic group on Long Term Rural Vision undertook a ‘rural voices’ consultation – with 170 contributions from 19 Member States and 3,000 people participating in workshops. The following overarching points emerged from the consultation:

- Rural Europe is highly differentiated and that differentiation is important in shaping local people’s vision of the future.

- Demographic change providers a barometer of possible opportunities – from attracting diaspora back to welcoming new residents; and this all requires more emphasis on viable public infrastructure and decent jobs to create a ‘more equal playing field’ with urban areas.

- COVID-19 has made it hard to detect a vision of rural Europe 20 years into the future – whilst the challenges of the ‘here and now’ predominate, the vision should take practical steps towards the longer view.

- The importance of available, affordable and accessible high-quality digital infrastructure.

- The need to put in place basic services and appropriate infrastructure to achieve the long-term vision.

- The strength of community spirit, volunteering and social support in rural communities – but the need for capacity building to maintain these activities.

- Concerns were expressed about climate change, environmental degradation and pressure from unsustainable agricultural practices.

- The need to develop holistic, place-based strategies with local communities.

In March 2021, a Rural Vision Week conference was held by the ENRD to triangulate the findings from all of the workshops and public consultations. In April 2021, a Eurobarometer survey was carried out to assess the priorities for the vision. The survey found 79% of respondents supported the European Commission giving consideration to rural areas in public spending decisions; 65% of those surveyed thought that local areas or provinces should be able to decide how European rural investment is spent; and 44% cited transport infrastructure and connections as key needs in rural Europe.

All of these consultation activities informed the final vision which was published by the European Commission on 30 June 2021.

What does the vision contain?

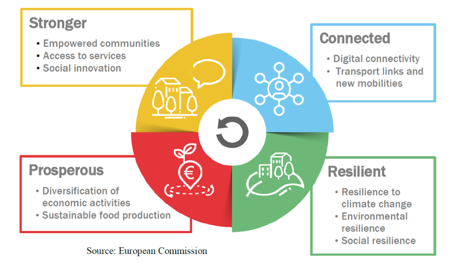

The vision is intended to drive stronger, connected, resilient and prosperous rural areas by 2040:

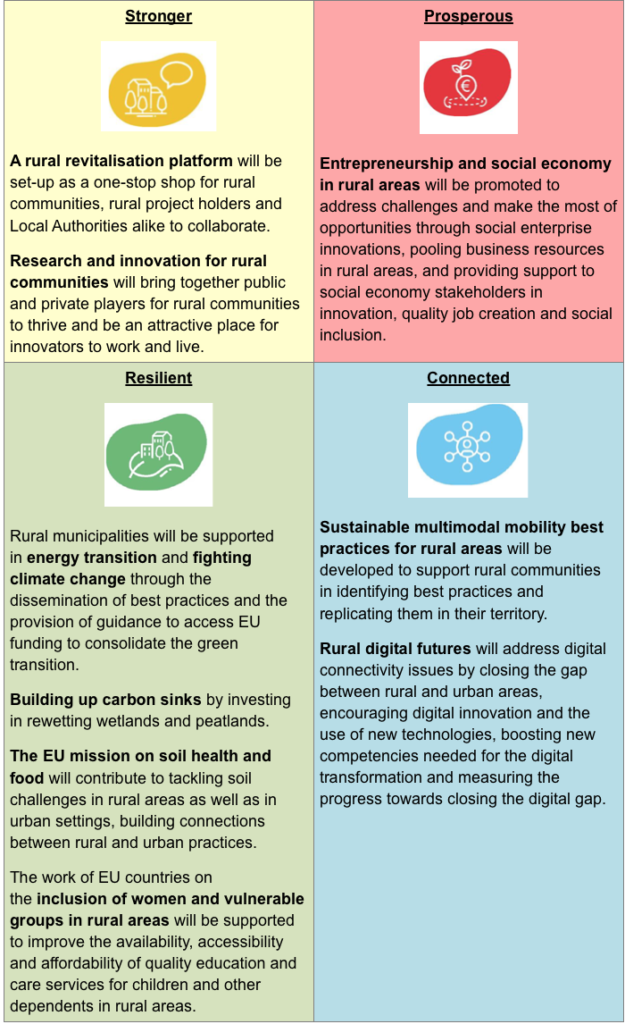

a) Stronger rural areas

“Innovation in rural areas is not led by big corporates. It is community-led”

This driver aims to ensure rural areas are home to empowered and vibrant local communities – where every individual can take an active part in policy and decision-making processes. The vision calls for the development of place-based and integrated policy solutions and investments. To ensure rural areas are attractive places to live and work, the vision calls for innovative solutions for the provision of services such as water, health care, transport, energy and digital communications.

b) Connected rural areas

“Broadband needs to be an essential service. It is a means to an end, not the end itself”

This driver is focused around maintaining and improving affordable transport services and infrastructure such as roads, railways and waterways. The potential for rural areas to act as hubs for the development, testing and deployment of sustainable and innovative mobility solutions should be further explored. Digital infrastructure is regarded as an enabler for rural areas to improve community capacity and their attractiveness

c) Resilient rural areas that foster well-being

This driver calls for rural areas to play a central role in the European Green Deal – preserving natural resources, restoring landscapes, greening farming and shortening supply chains to make rural places more resilient to climate change, natural hazards and economic crises. Different sustainable activities should be able to coexist (e.g. family agricultural activities should be carried out in harmony with other economic activities). This driver also seeks to strengthen the social resilience of rural areas – by tapping into the full breadth of talents and diversity in societies: from opening up good quality job opportunities in rural areas to paying particular attention to marginalised, disadvantaged and under-represented groups.

d) Prosperous rural areas

“Continue the commitment to support the diversification of activities and functions of rural areas…providing greater support for small and micro scale projects, especially promoted by young people and unemployed, avoiding their leaving for the cities”

This driver calls for the diversification of economic activities based on sustainable local economic strategies. This should provide rural communities with access to digital infrastructure, skills and support entrepreneurial mindsets. The important role played by agriculture, forestry and fisheries should be preserved – labelling schemes and advertising campaigns should acknowledge the quality and variety of local and traditional food products.

Taken as a collective, these four drivers are intended to deliver the following common aspirations of rural communities and stakeholders by 2040:

- Rural areas are attractive spaces, developed in harmonious territorial development, unlocking their specific potential, making them places of opportunity and providing local solutions to help tackle the local effects of global challenges.

- Rural communities are engaged in multi-level and place-based governance, developing integrated strategies using collaborative and participatory approaches, benefitting from tailor-made policy mixes and interdependencies between urban and rural areas.

- Rural areas are providers of food security, economic opportunities, goods and services for wider society, such as bio-based materials and energy but also local, community-based high-quality products, renewable energy, retaining a fair share of the value generated.

- Rural dwellers make up dynamic communities focusing on well-being, including livelihoods, fairness, prosperity and quality of life, where all people live and work well together, with adequate capacity for mutual support.

- Rural communities are inclusive of inter-generational solidarity fairness and renewal, open to newcomers and foster equal opportunities for all.

- Rural areas are flourishing sources of nature, enhanced by and contributing to the objectives of the Green Deal, including climate neutrality, as well as sustainable management of natural resources.

- Rural residents and businesses fully benefit from digital innovation with equal access to emerging technologies, widespread digital literacy and opportunities to acquire more advanced skills.

- Rural communities comprise entrepreneurial, innovative and skilled people, co-creating technological, ecological and social progress.

- Rural areas are lively places equipped with efficient, accessible and affordable public and private services, including cross border services, providing tailored solutions (such as transport, education, training, health and care, including long-term care, social life and retail business).

- Rural areas are places of diversity, where communities make the most out of their unique assets, talents and potential.

These 10 shared goals are intended to endorse the vision.

How will the vision be implemented?

The European Commission has embedded the vision under ‘priority 6 – a new push for European democracy for 2019-2024’ – which is set against a backdrop of digital transition, green transition, and COVID recovery.

The European Commission has published an EU Rural Action Plan and is developing a Rural Pact.

The Action Plan sets out tangible projects and initiatives. It is based around the four drivers of activity, targeted at bringing together different EU policy areas:

The European Commission intends to monitor and regularly update its Action Plan. Significantly, the development of the vision has led to a renewed focus from stakeholders on assessing EU policies through a rural lens. As part of the Better Regulation Agenda, the European Commission intends to put a rural proofing mechanism into place – this is intended to assess the anticipated impact of major EU legislative initiatives on rural areas and will include regular rural proofing monitoring reports.

The vision requires more and better data to be made available to better understand the social, economic and environmental conditions on rural areas. To deliver this, the European Commission is setting up a Rural Observatory to improve data collection and analysis on rural areas. The Observatory is tasked with centralising and analysing data [through a rural data portal], informing on relevant EU initiatives for rural areas, and analysing the achievements of the Rural Action Plan.

To improve synergies and complementarities between funds that contribute to rural development, the European Commission is developing a toolkit on access to and optimal combination of EU funding opportunities for rural areas. This will present all funding opportunities in one document and be accessible to Local Authorities, stakeholders, project holders and managing authorities. The toolkit is intended to support rural areas to take up new opportunities offered in the 2021-2027 budget.

Throughout 2021 the European Commission is developing a Rural Pact. This is intended to set out the path to achieving the goals of the vision. In mid-2023, the European Commission intends to take stock of the actions carried out so far, programme in support schemes to 2027, and highlight any gaps to address beyond the current funding period. These findings will be publicly available in early 2024 and feed into preparations for the 2028-2034 programming period.

Supporting much of this work, the ENRD thematic group on the Long Term Rural Vision workplan [covering the period July 2020-July 2021] is focussed around facilitating discussions with National Rural Networks and other national, regional and local stakeholders.

What does the vision offer to rural areas outside of Europe?

While there can be drawbacks from looking at visions from elsewhere – not least because these documents are always context, place and community specific; how might we exchange ideas and practice around #Rural2040? I offer eight reflections.

- Drivers: there are lots of competing demands in rural areas – is a vision or strategy about ensuring residents have equal, equitable and/or fair access to services? Is it about producing food, protecting the environment and/or public goods? Growing the green economy and adapting to climate change? Preserving settlements and landscapes for visitors to enjoy? All of the above or something else? Should rural strategies focus on broad issues (e.g. population growth or decline), target specific issues (e.g. access to health or education services) or both? #Rural2040 was developed in response to public consultations that found the role and importance of rural areas is under-appreciated and that many residents feel left behind by society and policy-makers. The vision was developed to address their challenges and concerns and to identify ways of improving rural quality of life. #Rural2040 is both strategic in the topics it encompasses (e.g. demographic change, digital infrastructure, access to services) but also translatable into practical actions (e.g. a training centre on rural innovation, digital innovation hubs to roll out digital infrastructure, the carbon-farming initiative).

- Places – the recently adopted Territorial Agenda is a strategic document for spatial planning in the European Union. It is anchored in place-based approaches and the involvement of stakeholders at all governance levels in order to make the most of the potential of rural areas. This approach begins to move away from administrative definitions to more functional definitions of rural that capture the realities, complexities and interconnectivity of rural places. Visions or strategies need to be ‘place appropriate’ in recognising the heterogeneity of rural areas.

- Deliverability: the European Commission intends to monitor the implementation of the EU Rural Action Plan and liaise with Member States, stakeholders, bodies and institutions on a regular basis to offer a platform for exchanges on rural issues. The Action Plan contains flagship projects and initiatives that the European Commission and Member States wish to implement. As per #Rural2040, how can we ensure rural visions and strategies are shared across national, regional and local stakeholders – whilst being clear on who is responsible and accountable for their implementation?

- Resources – the European Commission is developing a toolkit on access to funding opportunities for rural areas, seeking to make full use of the 2021-2027 budget and programming in investment for the budget in 2028 and beyond. In addition, the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) and InvestEU, the European Investment Bank (EIB) is also able to contribute to existing investment gaps in rural areas. More widely, policy and decision making is often driven by a ‘worst first’ approach in that public funding is targeted at those communities deemed the most challenged or deprived. This can often divert attention away from other rural communities that, with a bit of resource, could thrive. Moreover, some visions or strategies are not accompanied by any mandatory funding at all. They can also be time-limited and provide uncertainty rather than stability. How much public funding is being invested in rural areas – and what methodology or approach is being used to estimate the figures (e.g. population, need, geography). How much does it cost to deliver projects and initiatives in rural areas and how much money is being spent and by whom? Rural visions or strategies need to recognise the strong relationships between residents, businesses, the voluntary and community sector and local groups who often form the basis of action. With less access to services than their urban counterparts, many rural communities set up or run a service on their own account because of public sector funding reductions and/or market failure – what do we actually need to invest in our rural areas to help them thrive?

- Rural lens –the European Commission will be introducing a new rural proofing mechanism to assess the anticipated impact of major legislative initiatives on rural areas. This will draw upon ‘territorial impact assessments’ and better monitoring of the situation of rural areas. In March 2021, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) published its first cross-government rural proofing report. This is intended to provide a baseline for evaluating performance over time – and includes sections on economy, infrastructure, services and the natural environment. Notwithstanding how rural and urban areas are intertwined, all too often the starting point for rural documents is urban based i.e., policy makers seek to understand how rural areas are different from urban areas by concentrating on built up areas – defined according to their population size, density, access to services or type of land use etc. Applying a rural lens should seek to ensure that rural places and communities are able to take advantage of policies, programmes and practice.

- Bottom-up: over the last 30 years communities within the EU have been empowered to develop local strategies with CAP funding under the LEADER approach. Since 2007 local development has also been used within the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF) to support the sustainable development of coastal communities. More recently, the European Union’s cohesion policy has also seen Community-Led Local Development (CLLD) and the development of a Smart Villages approach. #Rural2040 builds on LEADER and CLLD in setting out how local communities are best placed to assess the relative strengths of their territories and to build upon them. This highlights the importance of taking a flexible and bottom-up approach in ways that fit the grain of different rural places and communities (e.g. terrior, eat the view).

- Data: #Rural2040 includes a commitment from the European Commission to establish a Rural Observatory which will work alongside EUROSTAT, the Joint Research Centre’s Knowledge Centre for Territorial Policies, ESPON and Horizon Europe. Data is often scattered across different platforms, in different formats, with different indicators. It is often collected for a specific purpose without thinking through its wider applicability and significance. How can / will the Observatory bring together, process and present information about what it is like to live and work in rural areas? And, if you project data between now and 2040: does it become easier, stay about the same, or become more difficult to live in a rural area? This underlines the need to have a better understanding on what data we already have, how it can be interrogated, where the gaps are – and how these might be filled. We need to be able to use data in a more holistic way to better develop a picture of different rural places.

- Diversity: #Rural2040 aims to tap into the full breadth of talents in society, paying particular attention to young people, older people, people with disabilities, LGBTQI+, migrants and Roma communities. How can we work to ensure all voices in our rural communities are heard, ensuring the visions and strategies we develop are fair, inclusive and present opportunities for all?

From the fair deal for rural communities published back in November 2000 and the Rural Strategy Defra published in 2004, through to the Government-wide Rural Statement in 2012; all have sought to reaffirm the Government’s commitment to rural communities. And yet while some of these documents contained a vision for thriving rural communities in a living, working, countryside and stimulated discussions; they have not necessarily provided a platform or roadmap for change. Since 2019 the Rural Services Network (RSN) has been calling on Government to take the lead and work with interested organisations to produce a long-term and funded Rural Strategy for England.

In a speech in July 2019, the President of the European Commission, Ursula Von der Leyen described rural areas as being “the fabric of our society and the heartbeat of our economy. They are a core part of our identity and our economic potential. We will cherish and preserve our rural areas and invest in the future”. Will #Rural2040 lead to a new and reinvigorated agenda for change or fail to address the different opportunities, challenges an barriers affecting European rural communities? Watch this space…

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

Jessica is a researcher/project manager at Rose Regeneration and a senior research fellow at The National Centre for Rural Health and Care (NCRHC). Her current work includes supporting health commissioners and providers to measure their response to COVID-19 and with future planning; and evaluating two employability programmes helping people furthest from the labour market. Jessica also sits on the board of a Housing Association that supports older and vulnerable people.

She can be contacted by email jessica.sellick@roseregeneration.co.uk.

Website: http://roseregeneration.co.uk/https://www.ncrhc.org/

Blog: http://ruralwords.co.uk/

Twitter: @RoseRegen