Making rural funding work better

‘Leader’ aims to provide an “integrated bottom up, community-led delivery of RDPE funding”. In England it is implemented by Local Action Groups (LAGs) and is targeted on rural areas with particular needs or priorities. In existence since 1991, and with negotiations around the 2014-2020 programme now intensifying, is Leader boosting the rural economy or is it an overly bureaucratic protracted process and waste of time and resources? Jessica Sellick investigates.

‘Leader’ is French for ‘links between actions for the development of rural economy’. Launched in 1991 by the European Commission, it is a way of delivering rural development in local communities through Local Action Groups (LAGs) rather than a fixed set of measures. This approach of ‘going local’ is carried out with the financial support of the European Agriculture Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD). Since its launch, Leader has been underpinned by seven key features: (i) area based Local Development Strategies, (ii) bottom-up elaboration and implementation strategies, (iii) local public-private partnerships/Local Action Groups, (iv) integrated/multi-sectoral actions, (v) innovation, (vi) cooperation, and (vii) networking.

Adapted from: ‘a review of the Leader approach for delivering the Rural Development Programme for England’, page 10.

In the current Leader programme (2007-2013), a minimum of 5% of each member state’s rural development programmes has been used to support the approach. There are 64 Local Action Groups (LAGs) running Leader across England, covering 52.5% of the rural population. LAGs are made up of interested volunteers from public, private and voluntary sectors. Each LAG develops a Local Development Strategy [putting the 7 key principles into action] and then funds projects in its locality according to this. Activity has mainly been funded across Axis 3 of the EAFRD (i.e., around quality of life in rural areas and diversification of the rural economy), with some parts of the country also able to fund activities under Axis 1 (i.e., improving the competitiveness of the agriculture and forestry sector). Looking at both the current programme and the transition to the next programme, is Leader providing a basis on which to think again about economic policy in rural areas? I offer four points.

Firstly, the Leader approach has been used to stimulate a plethora of projects and activities. Some 3,834 projects were supported across the 64 LAG areas between 2007 and January 2013. These projects varied from community growing and village furniture reuse schemes to new tourism actions and micro-business support. In many instances Leader has added value and made a real difference in localities. For example, Cumbria Woodlands received support from Solway, Border & Eden and Cumbria Fells & Dales LAGs and has delivered 37.5 full time equivalent jobs and generated £694,270 GVA directly as well as a number of agglomeration and wider community benefits around woodland management. The Coast, Wolds, Waterways and Wetlands (CWWW) Leader programme has invested £3 million in culture and heritage in 50 parishes (one-third of the total area covered by the programme). Leader funding has also been used to respond to crisis events – in Cumbria, the ‘Flood Debris Recovery Grant Scheme’ provided grants to farm holding affected by the November 2009 flood event. This enabled farmers to remove debris from their land so as to bring it back into agricultural production.

However, in some Leader areas there have been discussions around whether funding has focused enough on places with the greatest deprivation or need (or whether the length of time it takes to build community capacity in these areas is beyond a programme cycle); whether projects would have proceeded anyway without Leader support; if Leader really a ‘funder of last resort’ and – because EU rules set population thresholds that omit market towns and other service centres – is the Leader approach failing to recognise urban-rural linkages? Crucially, the pressures placed upon LAGs and staff in the current programme to focus upon spend and targets rather than outcomes have undoubtedly affected the projects which have come forward and received funding.

Secondly, if Leader is ‘a laboratory to encourage the emergence and testing of new approaches to integrated and sustainable development’, the administration is regarded by many LAG members, programme staff and project applicants to be unduly burdensome and complex. Whether the application is for a £3,000 community project or £300,000 business project, the same procedures have to be followed regardless of how low/high risk the project actually is. Some applicants struggle to cash flow their projects as Leader funding is paid in arrears whilst others experience difficulties seeking match funding and/or completing the claims paperwork. Indeed, even over the course a single project what is eligible and ineligible in terms of the rules can change:

“Part of the building is used for volunteers and part for delivering training. Some of the running costs were allowed but others weren’t so these had to be written off. It got to the point where only tea bags used by certain people connected to the project could be claimed back” – Project applicant.

Thirdly, as the current programme draws to a close, what happens next? In the EU’s next funding round (2014-2020), how can government ambitions for funding to be easier to access, go further and offer better value for money for the taxpayer be realised? In the case of Leader, the next programme cycle may not be in place until 2015. With the current programme ending this year, existing LAGs have applied for £30,000 transition funding to bridge the gap. However, this will not fund new projects rather it is to be used to support staff role(s), facilitate local groups and sustain networks At a European level, six priorities have been set out within the new Rural Development Regulation 2014-2020. They are: (1) knowledge transfer and innovation in agriculture and forestry; (2) enhancing the competitiveness of agriculture and farm viability; (3) promoting food chain organisation and risk management in agriculture; (4) enhancing ecosystems; (5) promoting resource efficiency; and (6) promoting social inclusion, poverty reduction and economic development. It is clear that Leader could operate across all six priorities with the specific focus determined by each LDS set at LAG level. Discussions are continuing around whether Leader should cover all of rural England (up from the current 52.5% coverage) – a move that would require either significantly larger Leader population thresholds or a significant increase in the number of LAGs. But what are we expecting from the next Leader programme and how can we make preparations now to ensure infrastructure, people and resources vital for delivering this does not fizzle out?

Fourthly, how can Leader function as a neighbourhood focused element of rural development policy, working alongside Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) and other bodies (e.g. Local Authorities, Rural and Farming Networks and Rural Community Councils)? The OECD Rural Policy Review of England found that while rural areas may have an economic structure that is not dissimilar from urban areas, there can be considerable variability within and across rural places. Moving away from headline initiatives and big ticket items, it is clear that Leader can respond to local economic conditions:

“Leader is an example of how to move away from flagship projects to be locally led and driven by community need. The projects that are funded may be small in cost/funding terms but are transformational in what they deliver” – East Cornwall LAG member.

Leader is a model that works; it mobilises the local community and economic actors, is driven by local need and fundamental to economic development…about being there for the local term and helping business growth in your local area” – Leader 4 Torridge and North Devon staff member.

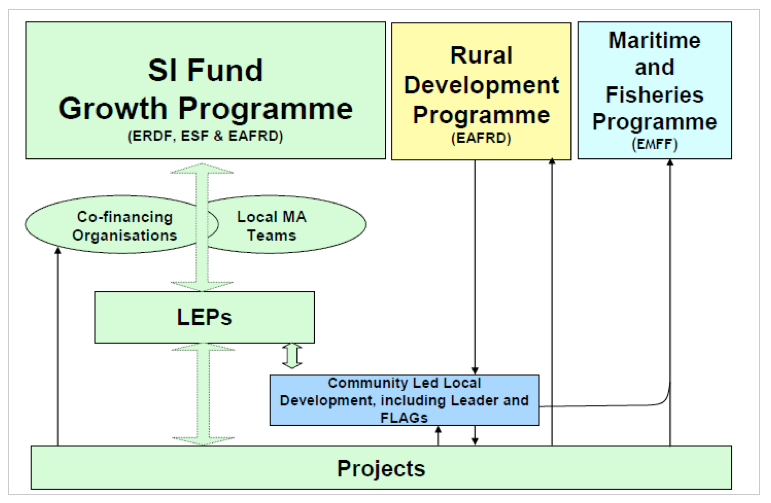

Yet how Leader interfaces with other bodies is still being worked through. In the diagram below, prepared for Local Enterprise Partnerships, Leader can be viewed either as an integral part of emerging economic policy or an after-thought:

Source: HM Government, Preliminary Guidance to Local Enterprise Partnerships on Development of Structural and Investment Strategies, BIS, 2012 (Technical Annex page 6).

The EFRA Select Committee Rural Communities report (published in July 2013) described how ‘with funding for national programmes being squeezed, this European funding has become a major resource for rural communities’ (page 80). If this is the case, how then can we ensure Leader is used to support communities looking to retain/develop services in their locality in the future? And how can we do this in a joined up way with LEPs and other bodies?

Jessica is a researcher/project manager at Rose Regeneration. She was part of the team that undertook a National Review of Leader for Defra and has worked on Leader funded projects in the South Pennines and North Pennine Dales. Her colleague Ivan has contributed a chapter on ‘The Role of Leader in Delivering Resilient Communities – the Rural Antidote to Growth at any Cost?’ in a forthcoming book on Rural Enterprise edited by Professors Collette Henry and Gerard McElwee (to be published by Emerald in 2014). Rose Regeneration is currently undertaking Leader Programme Evaluations for Cumbria Fells & Dales; Solway, Border & Eden; Yorkshire Dales; North Yorkshire Moors, Coast and Hills; Ayrshire; and Dumfries & Galloway. An overview and recommendations for the Coast, Wolds, Wetlands & Waterways LEADER Programme was recently completed. Jessica can be contacted by email jessica.sellick@roseregeneration.co.uk or telephone 01522 521211. Website: www.roseregeneration.co.uk Twitter: @RoseRegen