Central bank forecasting: do the models work for rural communities?

Economic models are quantitative frameworks used by almost all central banks, including the Bank of England (BoE), to test assumptions using economic data. Back in 2013, at his Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences lecture, Lars Peter Hanson said “part of meaningful quantitative analysis is to look at models and try to figure out their deficiencies and the ways in which they can be improved”. In April 2024, the BoE published a review on ‘forecasting for monetary policy’ led by Ben Bernanke, the former Chair of the Federal Reserve. What does this reveal about forecasting, how can it be improved, and why does this matter to rural communities? Jessica Sellick investigates. ………………………………………………………………………………………………..

When you think about a bank, you probably think about the branch where you access financial products and services, or the online system you log into. A central bank, also called a reserve bank, a national bank or a monetary authority, is different: it is an institution responsible for implementing monetary policy, managing currency, and controlling money supply at a country-level.

Central banks are typically responsible for:

- Defining monetary policy: they set macroeconomic objectives such as ensuring price stability and/or economic growth. To do this they have tools they use to set official interest rates – they can opt to increase this rate [to control inflation] or decrease it [to boost economic growth].

- Regulating money in circulation: they have the authority to issue coins and notes. They can inject liquidity into the economy, and ensure exchange rates remain stable.

- Overseeing the inter-bank market: they monitor national payment systems and ensure financial laws are being followed.

- Loaning liquidity to commercial banks: financial institutions can receive liquidity to cover what they need in the short-term (if/where required) while central banks ensure price stability by mediating in credit fluctuations.

- Independent: they are not aligned to any political party or group.

- Advisory role: they produce reports that are useful for Government, businesses and the general public.

In the United Kingdom, the Bank of England (BoE) is responsible for the central banking system. Other central banks include the Federal Reserve in the United States, the Reserve Bank in Australia, and the Swiss National Bank. Central banks can also represent a group of countries, for example, the European System of Central Banks (ESCBs). This is made up of both the European Central Bank (ECB) and all the national central banks of the countries within the European Union, whether they have the Euro as their official currency or not. The Bank of Central African States (BEAC) is a central bank that serves 6 countries which form the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC): Cameroon, Central Africa Republic, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and the Republic of the Congo.

How and why do central banks do forecasting? For central banks, economic forecasts are important for two reasons. Firstly, to inform policy and communicate policy plans and rationales to financial markets and the public. To do this, they need a representation of the economy they are attempting to direct, and a projection that takes account of forces affecting the economy over time (with short, medium, long and variable legs).

In practice, and simplified, this is analogist to having a core spreadsheet drawn from national accounts (e.g. consumption, investment, exports) which is then linked to other spreadsheets which provide a greater degree of disaggregation. It is also necessary to project items contained in the core spreadsheet (e.g. developments in the macroeconomy, exchange rate movements and taxes levied by a Government). Forecasts can model different scenarios (i.e., modelling something specific such as lower or higher unemployment rate than currently believed, or a 15% increase in energy prices). This scenario analysis can also be used to investigate errors in previous forecasts.

The construction of economic forecasts at central banks is normally undertaken by internal staff, with some input from policymakers. Central banks use different types of macroeconomic models for forecasting. The BoE, for example, uses a Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) model called COMPASS. This is built from microeconomic representations of the behaviour of individual households and businesses and includes 18 variables. This can be complemented by sectoral models (which focus on a particular sector of interest such as energy or housing), statistical models (which estimate changes in variables over time in light of changes in the past), and ‘big data’ (such as anonymised credit card records). Staff and policymakers also identify and correct for factors not adequately captured in these models and forecasts. While COMPASS remains the BoE’s benchmark model, over time the BoE has reduced its focus on COMPASS for generating a baseline forecast and placed greater emphasis on sectoral and statistical models.

The Bank of England Act 1998 gave responsibility for monetary policy to the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC). The MPC has nine voting members, and a non-voting representative from HM Treasury. The nine voting members comprise five internal BoE staff [the Governor, 3 deputy governors and chief economist]; and 4 external voting members appointed by the Chancellor of the Exchequer for renewable three-year terms. Under the 1998 Act the MPC is responsible for producing a quarterly report that contains:

- A review of monetary policy decisions published by the BoE.

- An assessment of the developments in inflation in the UK.

- An indication of the expected approach to meeting the BoE’s objectives of price stability, and supporting the Government’s economic policies.

- A series of fan charts to summarise the uncertainty surrounding the forecasts of inflation, GDP growth and unemployment over the next 3-years.

Five weeks before the report is published staff at the BoE working on the forecasts convene a ‘constraints meeting’ which looks at the current quarter and following quarter to estimate the key variables that will be important. There are also Key Issues and Benchmarking meetings with MPC members to discuss the forecasting and assumptions. One week before the policy meeting an official draft meeting is held to discuss the near-final forecast. Formal policy decisions are discussed at MPC meetings on a Friday, and the following Tuesday, with the official voting on the policy taken on the Wednesday.

Forecasting is difficult under the best of circumstances, and economies are prone to unexpected shocks (e.g. war, pandemic). There is also a lag in the economic data which means a rough snapshot, subject to revision, is provided. When a forecast proves to be significantly off-target, and this cannot be explained by unexpected shocks, the modelling should be reconsidered and policies modified.

Back in May 2023 the Bank of England’s (BoE) Court of Directors decided to commission a review into the Bank’s forecasting during times of significant uncertainty. The purpose of the review was to strengthen the Bank’s approach to supporting the MPC. They asked Ben Bernanke to lead the Review into the BoE’s current approach to forecasting, to compare this approach to other central banks, and to make recommendations for constructing and using forecasts in the future.

Grading economic forecasts – which ones pass? The Review by Bernanke compared the BoE’s forecasting accuracy since 2015 with six other central banks (the Bank of Canada, the US Federal Reserve, Norway’s Norges Bank, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Swedish Riksbank and the European Central Bank) as well as other external forecasters. This covered forecasts of inflation, GDP growth and unemployment. The Review also looked at ‘one quarter ahead’ forecasts [known as ‘nowcasts’]. Notwithstanding the timing of central bank forecasts are not uniform, and there were also a series of shocks that had different effects on different economies (e.g. COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine), the Review found:

“That the forecasting performance of all the central banks in our study, as well as that of external forecasters, deteriorated significantly with the onset of the pandemic and the subsequent inflation. The Bank of England suffered the common deterioration in forecast accuracy, but we find that, overall, its record is generally in the middle of the pack, and its policy response to recent developments, as indicated by changes in its policy rate, was also qualitatively similar to that of other central banks. There appears therefore to be little basis for singling out the Bank from its peers for criticism. At the same time, the marked decline in forecasting performance by all central banks (and other forecasters) provides strong motivation for reviewing the forecasting processes and the use of forecasts at all these entities, including the Bank [of England]”.

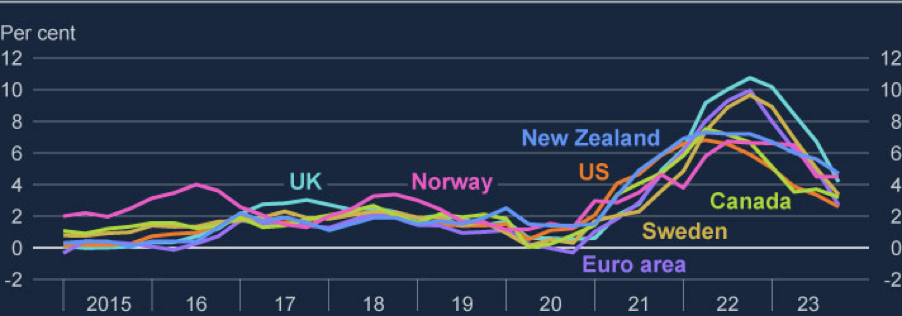

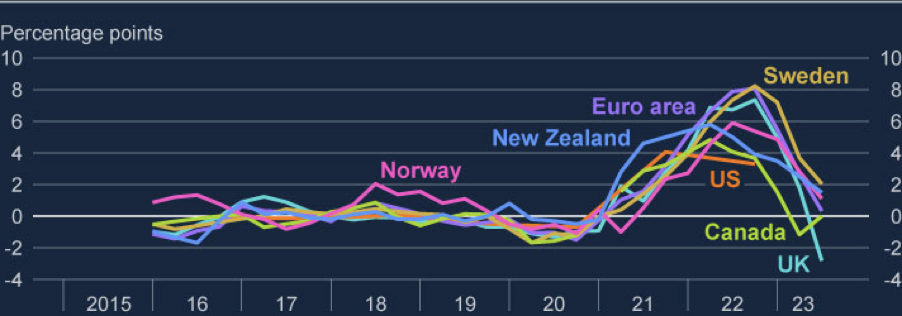

The Review contains a graph showing actual inflation rates since 2015 faced by the central banks in the set [figure 3], and a further graph showing the one year ahead forecasting errors by them [figure 4].

Figure 3: Annual inflation rates, 2015–23

Figure 4: Inflation, one year ahead forecast errors, 2015–23

The Figures highlight how all of the central banks were able to forecast inflation reasonably well one year ahead between 2015 and 2019, and even during 2020 [the first year of the pandemic]. However, the surge in inflation that began in mid-2021 was unanticipated by many central banks. When inflation was at its most extreme (in 2021 Q2 – 2023 Q3 period), the BoE’s forecast were better than those of the European Central Bank and Riksbank, but worse than those of the Bank of Canada, Norges Bank and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand.

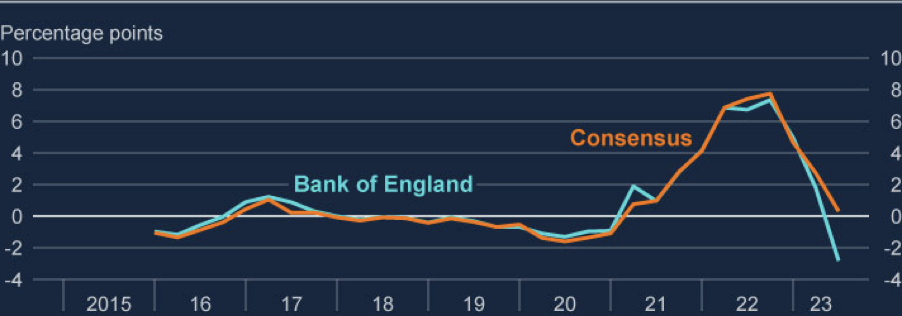

The BoE publishes comparisons of its own forecast errors with those of outside forecasters provided by Consensus Economics. For inflation, the Review confirmed that the forecast errors made by the BoE and those made by external forecasters were barely distinguishable [Figure 9]. Indeed, external forecasters failed to predict the post-pandemic surge in inflation as much as the central banks did [Figure 10].

Figure 9: UK CPI inflation rate, one year ahead forecast errors, 2015–23

Figure 10: UK four-quarter GDP growth, one year ahead forecast errors, 2015–23

While the BoE’s forecasting accuracy was not much different from that of other forecasters, the Review describes how the events of recent years have “nevertheless served as a stress test of forecasting at the Bank, including not only the routine construction of forecasts but also, importantly, the use of forecasts in policymaking and communication”.

The Review also looked at the quarterly forecast at the BoE, including the people, systems and communication used to develop these. The Review praised the competence and dedication of Bank staff, citing how their presentations of the forecast are professional, how they are responsive to questions and comments from MPC members, and how they revise and write up forecasts on short notice. On systems – the software and models used to produce the forecasts – the findings were less favourable:

“Some key software used in preparing the forecasts is out of date and lacks important functionality. Moreover, many of the economic and statistical models that support the forecast are not adequately maintained (updated, stress tested, periodically re-estimated). The models are also not smoothly integrated with each other…The incorporation of staff and MPC judgements into the forecast is likewise operationally complex. Makeshift fixes of these and other operational problems over the years have resulted in an unwieldy and inflexible system that limits the ability of staff to undertake potentially useful analyses”.

The Review describes how the baseline economic model, COMPASS, has significant shortcomings and indicates that an upgrade of the data management system is underway.

What more can be done to improve models and forecasting? The Review made 12 recommendations organised under three themes: infrastructure, decision making and communication.

The BoE needs to build and maintain a high-quality infrastructure for forecasting and analysis. The Review made recommendations around:

- Continuing the updating and modernisation of software to manage and manipulate data as rapidly as feasible – including ensuring staff can easily search for economic/financial data, can export and transform it, and the inputting of data becomes as automated as possible.

- Dedicating staff time and resources to maintain and update the model – and ensuring that models are regularly evaluated and re-estimated when new data becomes available, and stress tested against scenarios.

- Thoroughly reviewing and updating the forecasting framework, including replacing or revamping COMPASS – this should take account of the monetary transmission mechanism, short and long-term inflation expectations, key sectoral models (e.g. finance, housing, energy), and supply-side factors (e.g. productivity, labour supply, trade).

The BOE needs to provide a forecasting process that better supports the MPC’s decision-making. The Review identified a bias towards making incremental changes in successive models together with human judgements, at the expense of recognising structural changes in the economy. The Review made recommendations around:

- Charging staff with highlighting significant forecasting errors and their sources, particularly errors around unanticipated shocks. Staff should meet with MPC members to consider if structural change, misspecification of models and/or faulty judgements warrant changes to key assumptions and modelling approaches.

- Reviewing personnel policies to see if existing staff can be redeployed in ways that improve the forecasting infrastructure and forecast quality.

- Augmenting the central forecast with alternative scenarios, with these decided upon at an early stage during each forecast round by the MPC and staff.

Relative to other central banks, the Review highlights how the BoE relies heavily on its central economic forecast as a communications device. The recommendations include:

- Publishing selective alternative scenarios along with the central forecast to better help the public understand the policy choice.

- Giving more attention to published alternative scenarios in discussions about outlook and policy.

- Replace or reduce the detailed quantitative discussion of economic conditions in Monetary Policy Statements in favour of a shorter and more qualitative description.

- A section of the Monetary Policy Reports should be devoted to uncertainty and the balance of risks in the forecast.

- Fan charts suffer from significant analytical weaknesses, have outlived their usefulness and should be eliminated.

The Review made a final, overarching, recommendation that implementation all of the changes proposed should be phased – with an initial focus on improving the forecasting infrastructure (committing additional resources to do so), followed by adopting changes to policy-making and then communications.

In April 2024, the BoE responded to the Review and set out its commitment to all 12 of the recommendations:

“Two broad themes underpin many of the Review’s assessments and recommendations and are likely to guide the design of future changes: [Firstly] substantial investment is needed, beyond that already underway, to develop key parts of the data, modelling, forecasting and evaluation infrastructure and the expert staff to support them…[Secondly] within an overall approach that assigns more prominence to risks and welcomes challenge to underlying assumptions, the role of the central projection and the MPC’s discussions surrounding it should be reconsidered”.

It is also worth acknowledging that it is difficult for the BoE to implement changes when regular forecasting for the MPC needs to continue and is programmed in – with one commentator comparing this to trying to fix a car while all its parts are moving!

Why does this all matter to rural communities? The BoE is responsible for keeping inflation [price rises] low and stable – with a Government set target of keeping inflation at 2%. Inflation is measured via a ‘shopping basket’ wherein the Office for National Statistics (ONS) collects around 180,000 prices of about 700 items. Known as the Consumer Prices Index (CPI), it includes datasets relating to 13 principal areas: food/non-alcoholic beverages, alcohol/tobacco, clothing/footwear, housing/household services, owner occupiers’ housing costs, furniture/household goods, health, transport, communication, recreation/culture, education, restaurants/hotels and miscellaneous goods and services.

Rural residents are likely to have different consumption habits and face different financial pressures compared to their urban counterparts. Examples include:

- Transport: while the average number of trips is only marginally higher in rural areas compared to the national average, the total distances travelled are much higher with a higher proportion of these journeys made by car [90% in rural villages, hamlets and isolated dwellings compared to 72% in urban conurbations]. Car ownership in rural areas is essential for getting from place to place whereas urban residents can more easily choose from other options such as public transport, walking or cycling. Longer journeys means rural residents spend more money maintaining, repairing and replacing cars so an increase in automotive inflation may affect them more than their urban counterparts.

- Housing affordability: housing in predominantly rural areas is, on average, less affordable than in predominantly urban areas (excluding London) – in rural areas 9.2 times the lower quartile average earnings. The stock and quality of housing in rural areas also leaves homeowners and renters vulnerable to rising heating and utility costs, and additional maintenance costs.

In the United States, researchers have looked at US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Surveys and the Consumer Price Index to highlight the inflation disparities of rural households. They found rural households experienced considerably higher inflation than urban households did, especially relative to what was the case before the 2021 inflationary episode.

Back in the UK, in 2022 the Welsh Parliament’s Economy, Trade and Rural Affairs Committee conducted an inquiry into the cost-of-living crisis. As part of the inquiry, Parliament published an article summarising the cost of living pressures affecting people living in rural areas. This focused on the additional energy costs faced by rural residents who are off-grid and the lack of insulation/energy efficiency of rural properties. Echoing the findings of researchers in the United States, the article referenced work undertaken by The Bevan Foundation which found the average rural household spends £641.10 per week on essentials, compared to £572.90 for the average urban household.

Similarly, in Scotland, in 2023, The Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) and the Young Academy of Scotland (YAS) responded to a Scottish Affairs Committee’s consultation on the impact of the cost of living in rural communities in Scotland. The RSE and YAS working group found major societal events such as the cost of living crisis, the increase in fuel prices, COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine war had a greater impact on remote rural areas than on urban areas:

“The prices in remote rural communities for some essential goods were already higher than those in urban centres. And the recent increases in inflation have further exacerbated living costs pressures for remote rural Scotland. There is general scarcity of quality data regarding rural communities. The RSE recommends that policymakers regularly commission and monitor high-quality, robust statistical evidence. Research is essential to fully comprehend the complex picture of the challenges rural areas in Scotland are grappling with. The key challenges for remote rural communities are related to the ‘rural premium’ whereby communities face higher costs for food, clothes and other household goods, energy bills and transport”.

While ONS has a personal inflation calculator, there is no overall substantive analysis showing when the cost of living goes up how/whether rural residents across disproportionately affected through their consumption habits. Current analyses of inflation use aggregated data that does not fully account for or represent rurality.

If some of the data we collect and put into the models better reflects rural circumstances (e.g. supply side, shopping basket), and if central banks can further improve their forecasting performance, we can better prepare rural economies and communities for the outlook and its possible impacts.

Where next? For me, one of the key findings of the Review was around the career ladder at the BoE. If you want a pay rise you have to move around within the organisation – as it common in civil service jobs. On the one hand, this means staff have well rounded exposure to different operations/parts of the business. On the other hand, it leads to generalists rather than specialists who can undertake and scrutinise key areas that are core to the BoE’s work.

“Ultimately there’s no alternative to judgment – you can never get the answers out of some model”, Lawrence Summers, What in the world happened to economics? 15 March 1999, page 66.

The BoE acknowledges that it will need to consider the design and implementation of the recommendations and will be providing an update on proposed changes by the end of 2024. Watch this space!

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

Jessica is a project manager at Rose Regeneration and a senior research fellow at The National Centre for Rural Health and Care (NCRHC). She is currently evaluating a service that supports older people to maintain their independence; and reviewing neighbourhood-based initiatives (NBI). Jessica also sits on the board of a charity supporting rural communities across Cambridgeshire and is a member of her local Patient Participation Group.

She can be contacted by email jessica.sellick@roseregeneration.co.uk.

Website: http://roseregeneration.co.uk/https://www.ncrhc.org/

Blog: http://ruralwords.co.uk/

Twitter: @RoseRegen