From community to brigade: the changing role of fire [cover] and rescue services in rural places

While the core work of fire and rescue services has always been firefighting, they also respond to a wide variety of other incidents – from flooding and road traffic accidents to people stuck in machinery. When someone dials 999 they are experiencing a crisis that could be life threatening; and they require and expect a timely emergency response. National guidelines that set response times for fire calls were first formulated by the Riverdale Committee back in 1936. They have been modified a number of times since then. If firefighting and emergency response is every bit as dangerous in rural areas as in urban areas, how can we ensure resources are deployed in ways that take account of rural communities? Jessica Sellick investigates.

………………………………………………………………………………………………..

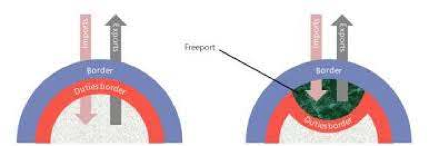

What is fire cover – and how has it been provided in rural places? Fire cover principally involves siting fire appliances in locations which best serve local conditions and meet nationally set standards of fire cover. Determining the optimum sites for resources – and how to do this in rural places – has evolved over time.

When the Royal Commission on Fire Brigades and Fire Prevention published its report back in 1923 it was of the view that “there are certain parts of the country which it would be uneconomic to protect, such as the hilly areas of Cumberland and Westmoreland, the Cotswold range of hills in Gloucester, or some of the mountainous districts in Wales and the Highlands of Scotland” (page 40). And yet, a civil servant called Arthur Dixon vowed to improve the provision of fire services in rural areas and two pilot schemes were set up in North Derbyshire and Norfolk. The schemes depended on Local Authorities in these areas cooperating through a joint board that could raise funds by a rate and make payments to participating brigades on a ‘fixed’ or ‘fee per fire attended’ basis. The pilot in Norfolk depended on the boy scouts identifying and preparing water supplies; and the North Derbyshire scheme resulted in a disproportionate contribution being made by authorities in towns to cross-subsidise provision in rural areas. At the end of the pilot period the Government decided the schemes would not address fire cover in other rural areas. However in North Derbyshire a ‘penny levy’ continued to fund the scheme until the Second World War.

In 1935, Arthur Balfour was appointed Chair of the Departmental Commission on Fire Brigade Services (known as the Riverdale Committee) – and his work led to the Fire Brigades Act 1938. The Act placed, for the first time, a statutory duty on Local Authorities to provide a fire service. The Act also required areas to be categorised according to their perceived level of risk – and this specified a minimum response times to fire calls. Four main categories of risk emerged: ‘A’ risks were those located in cities or towns (e.g. large shopping, business and entertainment centres); ‘B’ risks were situated in cities and towns not falling within category A (e.g. smaller-scale shopping and business districts); ‘C’ risks were found in the suburbs of larger towns and parts of smaller towns with built-up areas of substantial size; and finally ‘D’ risks included all other areas not falling into categories A to C, except remote rural. ‘Remote Rural’ areas were classified as ‘those areas isolated from centres of population and containing few buildings’. Attendance times were specified for risk categories A to D – from 3 pumps attending a category A and the first pump arriving within 5 minutes; through to 1 pump attending within 20 minutes for a category D. While some rural areas fitted into category D, there were no nationally recommended attendance times for Remote Rural areas.

The Riverdale Committee resulted in a model of risk where the lowest category was deemed ‘rural areas with scattered villages and hamlets’ – with these areas requiring an appliance to arrive within 20 minutes. The focus of the risk modelling was on saving property. In practice, these attendance times were difficult to implement in rural areas. Swathes of the countryside at that time had no fire service at all – with some areas providing equipment in sheds for local people to tackle the fire until an appliance arrived but the majority establishing fire posts with hand appliances. Fire extinguishing sat within parishes and rural district councils.

All of this led to debates about fire cover rules which had been drawn up to prioritise protecting buildings rather than lives and led to a disproportionate amount of funding being provided to urban areas – despite rates of death from fire correlated with attendance times and found to be higher in remote rural areas.

Until the 1970s, fire safety legislation was a spread over many pieces of primary and secondary legislation. The Fire Precautions Act 1971 was intended to include all premises over time. Initially, a designating order was made for hotels, offices, retail, railway premises and factories. This led to the creation of the Fire Precaution (Workplace) Regulations in 1997.

In June 1980, The Home Office published a Review of Fire Policy alongside a green paper for consultation. This contained proposals ‘to enable an adequate level of fire protection to be provided as economically as possible’. It recommended ‘greater selectivity in the attack on fire’, thereby targeting larger and more concentrated risks.

In September 2002, the Government invited Professor Sir George Bain, Professor Sir Michael Lyons and Sir Tony Young, to consider the future organisation of the Fire and Rescue Service. Their report ‘the future of the fire service: reducing risk, saving lives’ described how retained services were providing fire cover for around 60% of the UK’s land area, mainly rural areas (page 39); how a typical rural brigade control room would have 4 staff on duty at all times and deal with 2 calls an hour leading to a call handling incident cost of £50 in rural areas compared to £18 for the London fire service (page 40); and the need to better recruit, support and retain rural firefighters (page 67). The report resulted in a White Paper that led to changes in the primary legislation for the operation of Fire and Rescue Services as well as changes to firefighter pay and conditions which led to industrial action at the time.

The Fire and Rescue Services Act 2004 provides the main piece of current legislation under which fire and rescue services must operate. It sets out details of the statutory safety-orientated duties that fire authorities have. Beyond legislating for the duties and powers of fire and rescue authorities, the 2004 Act also introduced a Fire and Rescue National Framework. The Framework published in 2012 recognised the historic role of the service in putting out fires alongside increasing work on fire prevention. The Framework published in 2018 cited a significant decrease in the number of fires attended and to the testament of successful prevention and protection work. In July 2020, the Home Office published a progress report of Fire and Rescue Authorities’ compliance with the Framework. Each authority was required to provide assurance statements and, where appropriate, other documentation such as Integrated Risk Management Plans, Governance Statements and other operational and financial information. The report states: ‘having assessed this information, the Secretary of State is satisfied that every fire and rescue authority in England has acted in accordance with the requirements of the National Framework, and no formal steps have been taken by the Secretary of State since the last assurance statement in 2018 to secure compliance’.

As policy and legislative frameworks have been updated, the environment in which fire and rescue services operate has changed – bringing different governance models, a new inspectorate and the creation of the National Fire Chiefs Council (NFCC). While these frameworks set the overall strategic direction of fire and rescue authorities; authorities themselves remain free to operate in a way that ‘enables the most efficient and effective delivery of their services’. It is intended that fire and rescue authorities be accountable to their local communities rather than Government. Because the frameworks set high level expectations, they contain no specific references to rural which is viewed as an operational matter. Importantly, the 2004 legislation led to the abolition of national standards of fire cover, allowing local areas to set attendance targets. The Act also placed a statutory duty on authorities to promote fire safety and to manage community risk.

Collaboration has become an increasingly important feature of fire and rescue work. Under the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, Fire and Rescue authorities were designated ‘responsible authorities’. This means they are required to work alongside other responsible authorities such as Police, Councils, probation and clinical commissioning groups) on Community Safety Partnerships (CSPs).

The Policing and Crime Act 2017 introduced a statutory requirement for fire, police and ambulance services to collaborate if it is in the interests of each of their efficiency and effectiveness to do so. The Act also established a means by which Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs) could become directly involved in the governance of Fire and Rescue Services. This has led some PCCs to be redesignated Police, Fire and Crime Commissioners (PCPs). The Civil Contingencies Act 2004 provides a framework for organisations to plan and deal effectively with major emergencies. Here, Fire and Rescue Services are designated as ‘category 1 responders’ and are members are Local Resilience Forums (LRF).

Following the Grenfell Tower fire on 14 June 2017 in which 72 people so tragically lost their lives, there has been intensive work across and beyond Government leading to:

- The introduction of a Fire Safety Bill to clarify the scope of the Fire Safety Order.

- The creation of a new Fire Protection Board chaired by the National Fire Chiefs Council (NFCC).

- Increased funding to Fire and Rescue Authorities and the NFCC to increase fire inspection and enforcement capability.

The task of fire cover planning has changed over time – from a focus on protecting buildings in urban [A-C] and some rural areas [D]; to a prevention and protection response and integrated planning that focuses on saving lives. As fire service provision became set in statute, rural provision was sometimes viewed as needing fewer resources than their urban counterparts. With the abolition of national standards of fire cover and a preference for local target setting; calculating where to site appliances and fire fighters in rural areas needs to take account of the number and type of incidents, geography, the road network, resident needs, mobility (travel to work, visitors going to the countryside), other infrastructure and support available in rural places and the funding available. Locally set standards only apply to fire calls and fire and rescue services respond to many other incidents in rural places such as people stuck in equipment, animal rescues or floods alongside their prevention and protection work and for which there are no national targets or KPIs.

How are Fire and Rescue Services governed, funded and delivered? And has this changed during COVID-19?

All fire and rescue services are overseen by fire and rescue authorities (FRAs). There are 45 FRAs in England and the structure of each can slightly vary. Where a fire and rescue service shares a boundary with a single, upper tier council, the Local Authority is the fire authority and the FRS is an integral part of the authority alongside other public services. In other cases, where the FRS boundary covers more than one upper tier authority, a stand-alone Combined Fire Authority (CFA) is responsible for its governance. Other fire and rescue services cover airports, defence, royal properties, nuclear sites and ports.

FRAs must statutorily appoint a head of the paid service, a chief finance officer and a monitoring officer. FRAs are employing authorities that hire both uniformed (operational) staff and non-uniformed (support) staff.

The funding available to FRAs is provided by Government through the local government finance settlement (revenue support grant) and council tax. FRAs may also raise funds through charging for some non-emergency services, commercial trading activities, and/or applying for grants/research funding for specific purposes. The FRAs then make the decision locally to allocate this money to the specific areas for which they are responsible: prevention, protection and emergency response.

According to the NFCC and LGA, for the 29 standalone Fire and Rescue Authorities (FRAs) in 2009-2010 core spending power was estimated at £1.523 million, falling to £1.373 million in 2020-2021, equating to a cut of 28.55% in real terms. Home Office data on reserve levels between March 2015 and March 2019 found reserves levels at some authorities had significantly reduced over this time period – including in Derbyshire (by 60%), Buckinghamshire (by 50%), Durham & Darlington (by 38%), Cleveland (by 36%) and Humberside (by 34%); while in other authorities reserve levels remained the same (e.g. Hampshire and Nottinghamshire); and increased in other areas (e.g. Leicestershire, Hereford & Worcester, Devon & Somerset and West Yorkshire).

Analysis of the 2021-2022 local government finance settlement by the Fire Brigades Union (FBU) found brigades will receive £1.6 million more funding in 2021-2022 compared to 2020-2021, an increase of 0.18% in cash terms (and below inflation of 0.8% CPI to December 2020), equating to £37,200 per brigade. The FBU’s analysis reveals that from 2016-2017 to 2021-2022:

- 4 brigades have had their funding cut by more than one-third. West Sussex has lost £4.3 million (or 43.9%), Warwickshire £2.9 million (or 40.8%), Oxfordshire £3.2 million (or 38.2%), and Surrey £6.1 million (or 34.3%).

- A further 9 brigades have had their funding cut by more than £4 million, including Greater Manchester (£5.8 million or 10.2%), West Yorkshire (£4.8 million or 11.1%) and Devon and Somerset (£4.5 million or 16.8%).

- 42 brigades have had their funding reduced by at least £1 million since 2016-2017 – with most brigades experiencing cuts of at least 10%.

In March 2020, MHCLG announced emergency funding to Local Authorities in financial year 2020-2021 and additional support for 2021-2022. £28.5 million has been allocated to standalone Fire Authorities, with a further £6 million central fund made available to support services which are aiding Ambulance Services and coroners. For those sitting within county councils and unitary authorities, the additional funding is not ring fenced, with each authority setting the fire share.

Retained firefighters are mostly based in rural areas, crewing one or two appliances at a retained fire station, with some based in urban areas on stations alongside wholetime crews. The Home Office publishes workforce statistics for England. Covering the period April 2019 to March 2020, the data reveals a headcount of 35,291 firefighters of whom 22,793 were wholetime firefighters and 12,498 on the retained duty system. Analysis by the FBU reveals that since 2010 some 3,000 retained firefighter roles have been lost (and 8,000 wholetime roles). Despite an overall increase in retained firefighter numbers in 2019, levels fell in a number of brigades including Staffordshire and Surrey.

An Independent Review of conditions of service for fire and rescue staff back in 2015 found the retained system “offers significant opportunity to align resources to risk at a significantly lower cost that maintaining full time cover…However the difficulties in recruiting…[means] Government should bring forward legislation that extends employment protection (as enjoyed by military reservists) to firefighters engaged on retained duty systems and part-time contracts” (page 13). Research in 2016 sought to explore the motivations and barriers that influence individuals in urban and rural areas from becoming retained firefighters. This found people in rural areas had very specific motivators compared to their urban counterparts – with people living in rural areas wanting to help their local community. The NFCC has an employee guide setting out the skills required, time needed and terms and conditions for retained (on-call) firefighters.

In 2019-2020, 557,299 incidents were attended by FRSs in England – a 3% decrease compared with the previous year. Of all incidents attended, fire accounts for 28% of calls, with false alarms comprising 42% and non-fire incidents 31%. The total number of fires attended by FRSs has been decreasing over the past decade – from a peak of 474,000 in 2003-2004. Sadly, there were 243 fire-related fatalities in 2019-2020, the lowest figure since 1981-1982. For every one million people, there were 4.3 fire-related fatalities in 2019-2020. Over the same time period, FRSs and their partners completed 581,917 Home Fire Safety Checks (HFSCs) – 3% fewer than the previous year and 4% fewer than in the previous five year period. However, FRSs and their partners carried out 321,437 HFSCs targeted at people aged 65 years and over – this was 8% fewer than in the previous year but 32% greater than the five years previously.

The Home Office publishes fire statistics covering fires, false alarms, other incidents attended by fire crews, fatalities and casualties and response times. In relation to average response times, the data can be broken down by authority/geography and the Rural Urban Classification. This reveals for predominantly rural areas in 2019-2020, there were 10,671 primary fires and a response time of 10 minutes and 28 seconds; and for significantly rural areas 16,356 primary fires and a response time of 9 minutes 53 seconds. In predominantly urban areas there were 34,705 primary fires and a response time of 7 minutes 37 seconds. Primary fires are those where one or more of the following apply: i) all fires in buildings, outdoor structures and vehicles that are not derelict, ii) any fires involving casualties or rescues, iii) any fire attended by five or more appliances. The data spans a 10-year period and reveals how response times in predominantly urban areas have remained constant [around 7 minutes] while slightly increasing in predominantly rural areas (from 9 minutes 41 seconds in 2009-2010 to the current 10 minutes 28 seconds) and in significantly rural areas (from 8 minutes 44 seconds in 2009-2010 to the current 9 minutes 53 seconds).

In January 2021, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) published its report into the fire and rescue service’s response during the COVID-19 pandemic This found:

- Every service maintained its ability to respond to fires and other emergencies – with responding to emergencies prioritised over other protection and prevention activities. The overall number of incidents attended fell by 5% from 1 April to 30 June 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. 43 of 45 services had more fire engines available to respond to calls from 1 April to 30 June 2020 compared to the same period in 2019.

- Every service provided a range of additional support to its community that went above and beyond its statutory duties – with wholetime, retained and operational staff carrying out a wide range of support roles such as ambulance driving and food delivery.

- On-call [retained] firefighters were extensively deployed during the first wave of the pandemic to respond to emergencies – and their capacity to respond increased as some were furloughed from their primary employment or working from home. On-call firefighters were willing to work flexibly to fulfil a range of roles and services took steps to mitigate any financial hardship faced by individuals (e.g. offering them paid employment or short-term contracts if their primary employment was affected by the pandemic).

- The pandemic has been a catalyst for change and transformation – with staff redeployed and new IT and supporting infrastructure delivered [taking days rather than weeks or months to implement].

- Structural problems affected the way services operated during the pandemic – including the need to put in place the arrangements to carry out additional responsibilities to support partner agencies. Some chief fire officers did not have operational independence to allocate resources rapidly. But the Inspectorate highlighted how the sector came together through the NFCC to provide a coordinated response.

Central Government has historically been the main source of funding for fire and rescue services, but in recent years fire and rescue services have increasingly turned to council tax, making savings and/or dipping into reserves to set their budgets. With Government recently allocating more funding to fire and rescue will this lead to longer-term and more sustainable funding for FRAs? Retained firefighters have other employment but respond to incidents from their homes or workplace as required. In many rural areas, they provide the only source of fire and rescue cover. What more can be done to attract, recruit and keep retained firefighters? How can the contribution retained firefighters make be better understood, recognised and valued? How can we develop a better understanding of the work of FRSs in rural areas – and the services residents want and can expect? Throughout COVID-19, fire and rescue services maintained their ability to respond to fires and other emergencies whilst stepping up to take on a range of pandemic related tasks. There is now an imperative to restore public services while remaining prepared for future waves of the virus. What should guide restoration and recovery planning in the fire and rescue sector?

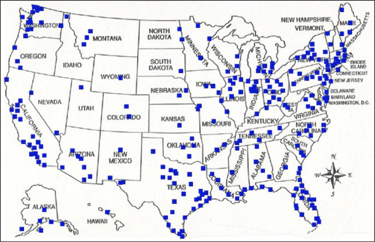

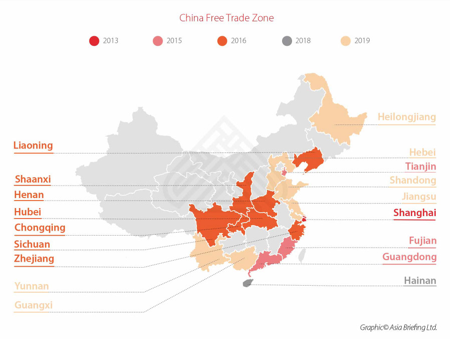

Like parts of the UK; Australia, Austria, China, France, Germany and the United States also rely upon volunteer firefighters in rural areas. In Australia, for example, they are known as ‘firies’ and they played a pivotal role in tackling unprecedented bushfires in 2019-2020. Approximately 195,000 Australians volunteer with the country’s 6 State and 2 Territory bushfire services – or 4.5% of the total rural population. In Queensland, for example, the Rural Fire Service (RFS) is made up of 36,000 volunteers – including 2,400 fire wardens sitting within 1,500 rural brigades. In New South Wales, the RFS is running a number of initiatives with farmers to help mitigate and respond to the threat of fires (e.g. farm fire plans, farm fire units, rural liaison officers). While funding varies by area, it is generated through state and territory levies – this pays for stations, vehicles, running costs, administration and training. As a result of the bushfires, some fire services have received public donations – with some of the money being used to help volunteers who had to take leave without pay.

The United States has a dedicated Rural Firefighting Academy (RFA). Developed by rural firefighters for rural firefighters, the RFA offers e-learning courses and publishes the ‘Rural Firefighting No Nonsense Handbook’. The RFA believes that fire departments need to communicate with the public and let them determine the level of emergency service they are willing to support. In rural areas, access to (and getting enough) water to the scene efficiently, recruiting and retaining enough volunteers, responding to different kinds of emergency incidents and working across rural fire departments (e.g. pooling training and planning sessions) are all more apparent compared to urban brigades.

In New Zealand, alongside responding to fires, Fire and Emergency NZ runs a Fire Smart initiative to help rural residents protect their home and property, and understand the response time of rural firefighters and first response units.

Finally, the Brandweeracademie (Fire Service Academy) in the Netherlands recently carried out a European research project looking at the recruitment and retention of volunteer firefighters. This considered the role of task differentiation i.e., meaning that a volunteer can be trained for specific tasks reducing the amount of time they spend on volunteering; and providing employers with benefits and rewards so staff can volunteer to go out to call.

What can we share with, and learn from, fire service organisation and delivery in other countries? How can we further develop community fire planning that identifies and address the needs of our rural communities (e.g. utilise data, consult with all members of rural communities, implement solutions – building safety, vulnerable residents – and monitor and evaluate initiatives)? And how can we ensure we have the workforce and equipment we need to respond to fire (and non-fire) calls in a timely and efficient manner in rural areas?

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

Thank you to all the RSN readers who contacted me following May’s rural words on oral health / dentistry. From requests for more data on the number of courses of treatment delivered by Urgent Care Hubs and people telling me how they had been removed from practice lists because they had not attended an appointment in the last two-years (even though you had been requesting one); through to those of you unable to restart treatment that began before the pandemic and/or being forced to pay for private treatment because you were in so much pain and the NHS waiting list so long. As a frequent user of dental services myself [though less frequent since COVID] I tried my very best to respond to all of your emails. Like many of you I too look forward to providers returning to their ‘normal contracted activity’. Thank you for all of your insights and feedback.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

Jessica is a researcher/project manager at Rose Regeneration and a senior research fellow at The National Centre for Rural Health and Care (NCRHC). Her current work includes supporting health commissioners and providers to measure their response to COVID-19 and with future planning; and evaluating two employability programmes helping people furthest from the labour market. She has previously worked with two Fire and Rescue Services to evaluate their community safety programmes. Jessica also sits on the board of a Housing Association that supports older and vulnerable people.

She can be contacted by email jessica.sellick@roseregeneration.co.uk.

Website: http://roseregeneration.co.uk/https://www.ncrhc.org/

Blog: http://ruralwords.co.uk/

Twitter: @RoseRegen

![fire extinguisher From community to brigade: the changing role of fire [cover] and rescue services in rural places](https://ruralwords.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/fire-extinguisher-1160x665.jpg)