Finding a place to call ‘home’: what more can be done to plug the rural housing gap?

Despite numerous consultations, announcements, funding packages, targets and interventions by successive Governments the housing gap remains – with the number of households [demand] outstripping the houses built [supply]. While rural places are often viewed as idyllic places to live, work and enjoy they face particular issues around affordability, accessibility and contain more second / holiday homes than their urban counterparts. How many homes do we need, and what more can be done to provide the rural homes people require? Jessica Sellick investigates.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………..

How many homes do we need, and are we delivering enough?

Back in 2015 the Coalition Government set out an ambition to deliver 1 million net additions to the housing stock by the end of 2020. In 2016 a House of Lords Select Committee on Economic Affairs report recommended the development of at least 300,000 homes annually for the foreseeable future.

In 2017 the Conservatives made a pledge to meet the 2015 commitment, and to deliver 500,000 more homes by the end of 2022. In January 2018, the Department for Housing Communities and Local Government (DCLG) was renamed the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG); and the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA) relaunched as Homes England and tasked with implementing the Government’s white paper to supply new homes. The white paper found ‘not enough Local Authorities planning for the homes they need; housebuilding is simply too slow; and the construction industry is too reliant on a small number of big players’. The white paper highlighted the need to:

- Build the right homes in the right places.

- Build them faster.

- Widen the range of builders and construction methods.

- Help people now – by investing in new affordable housing and preventing homelessness.

Since the white paper numerous consultations and policy developments have taken place. The Planning White Paper published in August 2020, for example, described the planning system as central to the failure to build enough homes and made a number of proposals to reform the system.

The current Government target is to provide 300,000 homes a year by the mid-2020s. Data shows that new supply has been increasing, reaching 244,000 completions in 2019-2020. Housebuilding starts fell in April-June 2020 as a result of COVID-19 [reaching levels similar to 2008]; though starts began to increase in July-September 2020.

Estimates published by the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) for 2019 show that housing completions since 2010 have averaged approximately 130,000 per year – below the current Government target.

According to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) Statistical Digest of Rural England (May 2021), between 2019-2019 and 2019-2020, the number of housing completions per 1,000 households increased in both predominantly rural and predominantly urban areas: with 10.5 dwelling completions in rural and 6.0 completions in urban areas. The Statistical Digest reveals how:

- There has been a steady increase in dwelling completions by Local Authorities and Housing Associations in predominantly rural areas: in 2019-2020 there were 2.1 completions per 100,000 households in rural areas compared to 1.1 completions in urban areas.

- In 2018-2019 in predominantly rural areas there were 64,700 net new dwellings, (or 12.8 per 1,000 households). This compares to 147,990 net new dwellings (9.4 per 1,000 households) in predominantly urban areas.

- New-build dwelling completions accounted for 90% of net additions to the housing stock in predominantly rural areas in 2018-2019, compared with 84% in predominantly urban areas.

- A further 8% of such net additions came from change of use of buildings in predominantly rural areas, compared with 14% of such net additions in predominantly urban areas.

- New-build dwelling completions per households in predominantly rural areas are higher than in predominantly urban areas: in 2018-2019 there were 11.6 new-build dwelling completions per 1,000 households in predominantly rural areas, compared with 7.9 in predominantly urban areas.

- In 2018-2019, the net number of dwellings arising from change of use in predominantly rural areas was 1.0 per 1,000 households and in predominantly urban areas it was 1.3 per 1,000 households.

According to a report by the National Housing Federation (NHF), nearly 8 million people have some form of housing need in England.

Research from Heriot-Watt University in 2019, estimated a housing backlog of 4 million homes; and the total level of new social housing at around 340,000 for England per year until 2031. They proposed this comprise 90,000 homes for social rent, 30,000 for intermediate affordable rent, and 25,000 for shared ownership.

Defra’s Statistical Digest suggests there are proportionality fewer homeless people and people living in temporary accommodation in rural areas compared to urban areas. However, research published by CPRE, the Rural Services Network and English Rural in October 2020 found homelessness in rural areas has doubled over a 2-year period: with the number of households categorised as homeless in rural Local Authorities rising to 19,975 – an increase of 115% from 2017-2018.

Crisis distinguishes between ‘core homelessness’ and ‘wider homelessness’. Core homelessness refers to households who are considered homeless at any point in time because they are living in short-term or unsuitable accommodation. This includes rough sleeping, sleeping in tents/cars/public transport, unlicensed/insecure squatting, unsuitable non-residential accommodation such as ‘beds in sheds’, hostels, night/winter shelters, domestic violence victims in refuges, temporary accommodation such as bed and breakfast accommodation and sofa surfing. Wider homelessness refers to people at risk of homelessness or those who have already experienced it and are living in temporary accommodation. This category encompasses staying with friends/relatives, being under notice to quit, being asked to leave by parents/relatives, in other temporary accommodation (e.g. social housing, private sector leasing), and/or being discharged from prison, hospital or other state institution without permanent housing. The research team at Heriot-Watt University used the main components of core homelessness and undertook statistical modelling to predict rates. The central estimates suggest in 2018-2019 the number of core homeless households in England was approximately 201,000.

Between April and December 2020, some 39,110 households secured accommodation through a relief duty which required Local Authorities to bring everyone living on the streets into self-contained accommodation as a response to COVID-19 [‘everyone in’] – 3,300 people were sleeping rough on approach.

Properties must be unfurnished and unoccupied for more than 6-weeks to be classed as empty. An audit of homes that have been empty for 5-years or more by Action on Empty Homes (AEH) found 400,000 empty properties. Almost 50% of the homes liable for the empty homes premium are in council tax band A. In 2020, 300 Local Authorities in England charged owners of long-term empty properties a council tax premium. Hotspots for where those in the higher bands were charged include Cheshire East, Buckinghamshire and Surrey. AEH also suggests there are thousands of empty homes that are furnished empties, often referred to as second homes, which comprise a further 263,000 homes and do not fit the empty definition and are not therefore charged a premium.

While the trend is for an increasing number of new homes to be supplied annually [with the Government working towards a target of 300,000 per annum], historically we have consistently been unable to meet any supply target(s) set. Such targets do not take account of the estimated 400,000 empty properties or 263,000 second homes. They also fail to take account of people with a housing need [4-8 million households], the 39,000 people housed as part of ‘everyone in’ or 201,000 households experiencing core homelessness. While some of the figures suggest the rate of new build completions is higher in predominantly rural areas when compared to predominantly urban areas, the rate of change of use is lower in rural areas. When looking at the datasets it can be difficult to understand how people in rural areas are being affected by the availability of housing in their local area – how many homes do we need in rural areas, and who for?

Are we delivering homes in the right places, to a high standard, and at an affordable cost?

Whatever the supply target, it is clear that providing a home for everyone who needs one is not simply about just building more houses anywhere. While there are severe housing shortages across the country, rural areas face particular difficulties. According to the Rural Services Network (RSN):

- Average house prices are £44,000 higher in rural areas than urban areas. Housing is less affordable in predominantly rural areas, where lower quartile (the cheapest 25%) house prices are 8.3 times greater than lower quartile annual earnings.

- Options for those on low incomes seeking social rented housing are typically limited in small rural settlements. Only 8% of households in villages live in social housing. By contrast, 19% of households in urban settlements live in social housing.

- The rural stock of social rented housing has shrunk under the Right to Buy policy, with sales quadrupling between 2012 and 2015 to reach 1% of the stock each year. Although the sale income is intended for reinvestment, only 1 replacement home was built in rural areas for every 8 sold during this period, and these replacements were rarely in the same settlement.

- Second homes and holiday lets often add to rural housing market pressures, especially in popular tourist areas. They form a particularly large share of the housing stock in some local authority areas – including, for example, Isles of Scilly (15%), North Norfolk (10%) and South Hams (9%).

Many of these difficulties were echoed in evidence given to the Parliamentary Inquiry into Rural Health and Care in 2020. Ms Jo Lavis (housing professional) described how, in 2019, just 5,558 new affordable homes were built in villages of less than 3,000 population, with 80% of those completions private sector dwellings. In 70% of rural communities it is not possible to gain affordable housing on-site from developments of less than 10 dwellings. Housing needs surveys undertaken by Rural Housing Enablers (RHEs) in 10 counties and 26 villages between January and March 2020 found:

- 383 households were looking for affordable housing.

- 71% of households were looking for a home to rent.

- 60% of households earned less than £30,000 per annum and half of them less than £20,000.

- 35% were aged 16 – 30 years and 21% 60 years and over.

- 42% were looking for a house and 56% looking for a bungalow/level access or adapted housing.

Stays of longer than 28 nights on Airbnb globally rose from 14% in 2019 to 24% in the first three months of 2021 with remote working one of the contributing factors. Rural nights booked in the UK have increased from 25% to 50% of bookings. A survey by ARLA Propertymark and Capital Economics found 470,000 properties could be removed from the long-term lettings market to short-lets; and 16% of all adults have let out all or part of their property (equating to 19% of the UK’s housing stock). There are concerns that the supply in the private rented sector will drop and rent costs will increase.

What are we building?

According to Defra’s Statistical Digest, in 2011 the majority of houses in rural villages & rural hamlets and isolated dwellings were detached properties. In 2018, the majority of new-build residential transactions were detached properties in both rural village & dispersed and rural town & fringe settlements, at 58% and 52% respectively. In 2018, there were 14,000 transactions for detached properties, a level four-times greater than in 2009. Flats made up the smallest proportion of new build transactions in rural areas, but the majority in urban conurbations (at 56%).

Regarding existing stock, in her evidence to the Inquiry, Ursula Benion (Trent and Dove Housing/Rural Housing Alliance) highlighted how rural homes are less likely to be updated; and rural areas tend to suffer from poorer broadband, which affects the use of technology to make rural dwellings more “liveable” and the desirability of rural places as communities to live in.

A decent home?

A report from the Centre for Ageing Better and Care & Repair England found more than 4.3 million homes in England did not meet basic standards of decency, most commonly because of the presence of a serious hazard to their occupants’ health or safety. Half of these homes are lived in by someone over 55 years of age, and a million homes contain at least one child. Households headed by someone over 75 years of age were found to be disproportionately likely to be living in a non-decent home, and the problem has worsened for this age group. Two million households headed by someone over 65 years of age find it difficult to heat their home. The largest number of non-decent homes is among owner-occupiers, with many facing financial or practical barriers to maintaining their home. Meanwhile 20% of all homes in the private rented sector were deemed ‘non-decent’.

Research from Shelter has looked at the impact of poor quality housing on mental health. 1 in 5 English adults surveyed (21%) said a housing issue had negatively impacted upon their mental health in the last five-years. 3 in 10 of those with a housing problem said they had experienced no issue with their mental health previously.

The Government is currently carrying out a review of the Decent Homes Standard. Part 1 will run to Autumn 2021 and seek to understand the case for change to criteria within the Standard. If the case for change is made, part 2 will run from Autumn 2021 to Summer 2022 and will consider how decency should be defined.

What’s affordable?

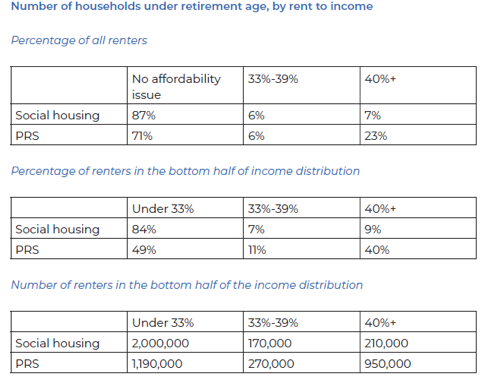

The Affordable Housing Commission has estimated that 1.6 million working age households in the bottom half of income distribution spend 33% of their net income on rent; with 1.2 million of these households paying more than 40%. Problems of affordability are heavily concentrated in the private rented sector where tenants have the least security. According to the English Housing Survey, in 2019-2020 privately-renting households spent more of their income on housing on average compared with other groups. On average, private renters spent around 32% of their income on rent, compared with 27% for social tenants and 18% on mortgage costs for mortgagors. Overall, the Commission reported that 1 in 5 households in England face some form of affordability issue. This was supported by the Church of England’s coming home report which described how: “in rural and coastal tourist destinations, even just a few homes being taken up as holiday or second homes can have a significant impact on local communities. Schools, churches and community organisations find it difficult to recruit pupils and members. Local businesses struggle out of season” (page 25).

In ‘making housing affordable again’, the Affordable Housing Commission analysed the proportion of income that lower-income households have to spend on housing. The tables below (page 68) indicate how problems of affordability are concentrated in the private rented sector where tenants have the least security; and in London and the South East where two-thirds of private sector tenants were found to be paying one-third or more of their income in rent:

There is no all-encompassing statutory definition of affordable housing in England and there is ambiguity in the way the term ‘affordable’ is applied in relation to housing. Often used to describe housing provided with public subsidy, it can also be applied to describe housing of any tenure that is judged to be affordable to a particular household or group by looking at housing costs, income levels and other factors.

In 2002 the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH) submitted evidence to the Transport, Local Government and the Regions Select Committee’s Affordable Housing inquiry in which it argued for precise and appropriate definitions of affordable housing. Then, the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (ODPM): Housing, Planning, Local Government and the Regions Select Committee conducted an inquiry into Affordability and the Supply of Housing in 2005-2006, choosing to define affordable housing as: ‘subsidised housing that meets the needs of those who cannot afford secure decent housing on the open market either to rent or buy’. Since then, within Government housing policy, affordability has been linked to below market prices and rents. Currently, ‘affordability’ as a technical term is defined in Annex 2 of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) as “(i) social rented, (ii) affordable rented and (iii) intermediate housing, provided to eligible households whose needs are not met by the market.”

While noting how the NPPF had incorporated these definitions in its 2019 update, the Affordable Housing Commission concluded in 2020 that “many of these products are clearly unaffordable to those on mid to low incomes”.

The housing cost to income ratio (HCIR) considers the proportion of a household’s disposable income spent on housing. This measure is widely used in studies of affordability. For example, the HCIR has been used by the Resolution Foundation in its research on affordability – identifying an overall trend is one of significant increases in housing costs relative to income. While the average family spent just 6% of their income on housing costs in 1961, today this has trebled to 18%. Among private renters, the average HCIR has increased from 9% in the 1960s to 36% today. In contrast, the average HCIR among outright owners is approximately 5%. In 2020, the Affordable Housing Commission proposed a definition of housing affordability which builds on the housing cost to income ratio by taking account of personal circumstances rather than market prices: ‘our measures are based on an affordability threshold at the point when rents or purchase costs exceed a third of net equivalised household income (and take account of related affordability issues, such as housing quality, overcrowding, adequacy of housing benefit, household size and regional variations)’.

Research by Savills, carried out on behalf of the National Housing Federation and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, in 2015 proposed the development of rented homes which would be accessible to a household in employment with rents based on the bottom quarter of local earnings, starting at a level based on 28% of that figure. The NPPF includes a standard method for calculating housing need which incorporates a housing costs to earnings ratio. Local planning authorities are expected to use the standard method when assessing local housing need as part of the Local Plan process. The standard method takes a baseline measure of projected household growth and adjusts this upwards, based on the ratio between the median house price in the area and the median annual earnings of full-time employees working in the area.

The NatCen takes a residual income approach to defining and measuring housing affordability, based on the Minimum Income Standard (MIS) – this details the income that different households are believed to need to reach a minimum socially acceptable standard of living in the UK. The approach states that housing is affordable to a given household ‘if they can afford to pay for their housing and have enough left over to cover what is needed to reach the minimum income standard for their household type’. However, some households have such limited incomes so that they would be below this standard even if they were to pay no housing costs. The housing affordability measure therefore takes into account whether households are below the minimum income standard because of their high housing costs rather than because they have a low income. The analysis presented back in 2016 revealed that at least one in five households in the private rented sector had unaffordable housing costs.

A comparison between MIS in 2008 and 2018 found that while in 2008 the MIS calculations used social housing as a starting point in calculating minimum costs for all groups, its limited availability means that private renting is now used as the MIS benchmark for working-age people without children – and is becoming the only option for many with children too. In the original MIS published in 2008, groups said that social housing would meet the needs of all household types. However in 2014, when the budgets for households without children were rebased (i.e., redeveloped from scratch with new groups), this was thought unrealistic for working-age singles and couples, while still being considered the lowest-cost socially acceptable housing for pensioners and parents. While a substantial number of working-age adults without children live in social housing, many of these are in vulnerable groups such as those with disabilities or addictions. It is perceived that, in general, there is little prospect for most people without children to get allocated social housing.

Local planning authorities may require developers to include an element of affordable housing on site as a condition of granting planning permission. Sometimes known as ‘section 106 agreements’, these are legally enforceable obligations. In 2019-2020, more than 27,000 homes were delivered through such agreements, of which 3,800 were for social rent. The NPPF states that ‘where major development involving the provision of housing is proposed, planning policies and decisions should expect at least 10% of the homes to be available for affordable home ownership, unless this would exceed the level of affordable housing required in the area, or significantly prejudice the ability to meet the identified affordable housing needs of specific groups’.

For too many people their homes are in a poor state and unsuitable condition. The new homes being developed in rural areas tend to be detached and do not necessarily meet the housing needs of some members of our communities looking to downsize, buy their first home, or move into an adapted property. What more can be done to ensure new builds meet the stock type needed locally? Such is the lack of consensus over what affordability means in housing terms, there are suggestions that the concept should be abandoned on the basis that it is unhelpful for describing the difficulties some households face in meeting their housing needs. Some rural places are now seen as the preserve of the rich with too few homes available for affordable rent and/or shared ownership. How might we measure what affordability looks like in different rural places? Rather than focusing on the number of new homes built, perhaps the balance should be on the location, tenures and affordability?

What impact has COVID-19 had – and how can we build back better and level-up communities?

In a speech on the economy in June 2020, the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, argued that “newt-counting delays in our system are a massive drag on the productivity and the prosperity of this country”, slowing down house building; and that in recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, we would “build back better and build greener but we will also build faster”. The Government published its white paper ‘Planning for the Future’ in August 2020. The paper contained a range of proposals – from local communities being consulted from the very beginning of the planning process, to protecting valued green spaces for future generations by allowing more building on brownfield land; and building homes more quickly by ensuring local housing plans are developed and agreed in 30 months rather than up to 7 years, through to every area requiring a plan in place to build more homes. In parallel to the white paper, the Government also launched a consultation on changes to the current planning system. The proposed changes cover four policy areas. Firstly, setting developer contributions for first homes. Secondly, raising the threshold at which developer contributions would be sought [section 106] for a limited time period to 40 or 50 homes. Thirdly, a new system to allow the Secretary of State to grant planning ‘permission in principle’. And fourthly, amendments to the standard method for calculating housing need to include percentage of housing stock levels and an affordability adjustment.

Numerous bodies have queried whether these new approaches will make it harder to achieve the Government’s target of 300,000 new homes a year and/or lead to the loss of the countryside. In response to an opposition day debate on local involvement in planning decisions in June 2021, Graham Biggs, Chief Executive of the RSN, described how: “proposals to reform the planning system are too simplistic and will not meet the many economic, social, and environmental needs of communities in rural areas. Residents and their parish councils must continue to be given a say about planning applications. A successful land use planning system needs to have both the ability and local flexibility to plan for rural communities which are sustainable in economic, social, and environmental terms, meeting the varied needs of small as well as large settlements. Current proposals set out in the Planning White Paper will need to be revisited and considerably revised if they are to deliver that objective.”

In response to COVID-19, the Government has already been making various changes to planning rules. Some of these changes relate to permitted development rights (PDRs), under which development may take place under a general permission granted by Parliament without requiring an application to the LPA for planning permission. Other changes – introduced through the Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) (Amendment) (England) Regulations 2020 – create new some use classes and abolish some old ones.

In a blog for the NHF in July 2020, Lord Best described what the impact of COVID-19 might have on housing in rural areas. He identified the following trends:

- Young people working or living in rural areas – perhaps with parents in council housing or in accommodation linked to a farming job – may find it harder than ever to find a place of their own nearby.

- With our new willingness to work from home and commute less frequently, homes in the countryside seem destined to be more in demand.

- Older people who had been thinking about downsizing a home or garden that is becoming less accessible and more expensive may have a change of mind – a care home may be avoided at all costs in place of access to fresh air, space and sunshine.

- For families on lower incomes, greater insecurity around employment and/or the erosion of savings may make home ownership or shared ownership a distant dream.

Urban flight?

According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), average UK house prices rose by 8.5% in 2020, despite the difficulties of physically valuing or viewing properties during periods of lockdown. In July 2020 the Chancellor announced the suspension of stamp duty on properties up to £500,000, a scheme was that due to end in March 2021 but has been extended to June 2021 when it steps down to £250,000, with the £125,000 threshold due to be reintroduced in September 2021. The Government has also announced a Loan to Value mortgage guarantee scheme intended to benefit first time buyers.

A survey of buyers and sellers registered with Savills back in May 2020 found 51% of people in London were considering a move outside the city [compared to 42% for the same period of 2019] and 30% were more likely to consider a village or countryside location for their next move.

According to Hamptons International, in 2020 London leavers purchased 73,950 homes outside the capital, the highest number in four years. Collectively, Londoners bought £27.6 billion worth of property outside the capital this year, the highest amount since 2007 when London outmigration previously peaked. This figure exceeds the total value of all homes sold in the North West last year (£24.8 billion). Sevenoaks recorded the biggest increase in the share of homes bought by Londoners with 62% of homes in the area bought by a Londoner, levels 39% higher than in 2019. Other hotspots for Londoners included Windsor and Maidenhead (+27%), Oxford (+17%) and Rushmoor (+15%).

Rightmove reported a 126% increase in searches for village locations in 2020. Most of the top village destinations were still within a commutable distance to a city, but with the appeal of a quieter way of life. It is thought that homeowners living in cities have benefitted from strong house price growth over the years and are now able to trade up and move to the countryside.

Research by Knight Frank and the Telegraph in June 2021 found market towns had been overlooked in the first lockdown – where people wanted remote and rural locations – but surged during the second lockdown. The research identified 12 market towns which scored highly in terms of crime levels, healthcare, education, affordability, and having something for everyone: Spalding (Lincolnshire), Ashbourne (Derbyshire), Stratford Upon Avon (Warwickshire), Arundal (West Sussex), Shipston-on-Stour (Warwickshire), Northwich (Cheshire), Tewkesbury (Gloucestershire), Kendal (Cumbria), Tenterden (Kent), Knaresborough (North Yorkshire), Lymington (Hampshire) and Haslemere (Surrey).

In March 2021, The Sunday Times published ‘the best places to live’ guide. The top listed rural places included Alnmouth (Northumberland), Charlbury (Oxfordshire), Denham Vale (Essex/Suffolk), Edale (Derbyshire), Isle of Eigg (Inner Hebrides), Surrey Hills, and Tisbury and the Nadder Valley (Wiltshire). The median house price varied from £299,950 to £675,000.

Home improvements and do it yourself?

As many of us have been spending so much time in our homes, we have become aware of how they do (and don’t) work for us. For some people, relying on our homes for everything – working, learning, relaxing, exercising, home schooling – and remaining in our property has led some of us to carry out home improvements.

Kantar estimated that we spent some £4.94 billion on improving our homes between September and December 2020, £552 million more than during the same period in 2019. A poll by MADE found 68% of consumers shopped online for home items at least once a month during 2020 while almost 1 in 5 (19%) did so multiple times per week. 40% of respondents claimed to have bought new home accessories throughout lockdown, and the same number rearranged their furniture, in search of a fresh perspective. This resulted in MADE witnessing a notable interest from consumers for multiple products from art (+117%) to bedding (+122%) and bathroom accessories (+177%). Research by Habito found 62% of home owners intend to undertake home improvements in 2021 – with one-third planning to re-mortgage their home to fund the improvements.

Generation(s) rent?

As the impact of the pandemic on earnings and savings becomes clear, Paragon Bank has estimated that more than one million older people will end up renting by 2031. According to the English Housing Survey, people aged 55 years and over are the fastest growing cohort of renters – with some 609,000 renting in 2019, double the figure when compared to 2009. COVID-19 is seen to be accelerating trends amongst older people including rising divorce rates, poorer pension returns and men living longer. Some suggest there is a trend amongst older people for flexibility, simplicity and freedom that renting offers.

Research from the Loughborough University found in the UK nearly two-thirds of people aged 20-34 years (some 3.5 million people) live in their family home, and this figure has grown during COVID-19 due to the impact of the pandemic on the mental and financial health of young adults.

During the Spanish flu in 1918, people fled the metropolis for the countryside. COVID-19 is seeing a similar phenomena with some people wanting to move to the urban fringe and others moving to remote rural areas as they see a future of fully remote working. While some sectors of the economy have been struggling (e.g. hospitality, travel), the DIY / home interiors sectors have been booming. With many of us re-evaluating our lives and where we want to live, will current and planned housing stock meet the economic realities facing people wanting to live and work in the countryside?

What more can be done to deliver the homes we need in the countryside?

According to Lord Best, “in the post-coronavirus era, it looks as if the tried and tested solutions for meeting housing need remain paramount. More homes for social renting in small developments that target local people, and a few purpose-built bungalows for older people to free up family homes, can make a huge difference for the village”.

Successive Governments have focused on building new homes with the intention of the additional supply reducing prices. But we are not hitting our targets for new homes, and nor are prices falling. If the current system is broken, what can be done to fix it – and fix it in rural areas?

The Rural Services Network is calling on the Government to produce a fully-funded, comprehensive rural strategy. Such a strategy should address:

- Bringing forward development sites at a price suited to affordable housing;

- Making sure such homes are, and remain, genuinely affordable.

- Planning new housing in ways which attract community support; and

- Ensuring the funding model for affordable house building stacks up.

The RSN believes that for rural to be affordable places to live, the following initiatives are needed:

- A planning policy to fit rural circumstances – allowing affordable housing quotas where they are most needed.

- A realistic definition of affordable – to meet the greatest need for social rented housing.

- A dedicated rural affordable housing programme – to boost delivery by housing associations in small rural settlements.

- A bolstering of landowner and community support – to release land for rural exception sites, at prices and under the assurance that they will only over be for affordable housing.

- A replenishing of social housing – ensuring that right to buy sale proceeds are returned to Local Authorities so they can reinvest it and replenish the stock of affordable homes.

In March 2021, the RSN launched ‘Revitalising Rural’ campaign. This sets out a number of key asks of Government to ensure rural areas are not left behind in the levelling-up agenda and that they are considered in post-pandemic policy making. On housing, the campaign makes specific asks around affordable housing quotas, grant funding, community-led housing, exception sites and the proceeds of the sales of affordable homes.

The Commission on Housing, Church and Community was launched in April 2019 with a remit to re-imagine housing policy and make recommendations to Government; and to look at what actions the Church of England could take with others to tackle the housing crisis. The Commission published it report ‘Coming Home’ in February 2021. This explored some of the reasons for the mis-match between activity and outcomes. The Commission echoed the need for a long-term housing strategy: ‘What does the Government aspire to for these various tenures by 2030 and 2040? What does the Government aspire to in terms of the affordability of housing, owned and rented, defined in relation to household incomes? What does the Government aspire to in terms of the condition, and environmental sustainability of the housing stock? Without clarity on these longer terms goals, the housing policies of successive governments have been characterised by short-term interventions and announcements’ (page 75). The Commission also called for investment in existing housing stock – with a focus on safety, on ensuring private rented homes are affordable to people on low incomes and a review of social security changes. The Church of England has developed a range of theological resources to make connections between faith and housing. Much of this work is building on the Faith in Affordable Housing project, which works with all denominations in England and Wales to release surplus land or buildings for affordable housing.

The Rural Housing Alliance (RHA) and National Housing Federation (NHF) have developed a 5-star plan for housing associations and the wider rural housing sector. Endorsed by the RSN, the plan focuses on delivering more quality homes that meet local needs through partnerships with rural communities and landowners. Under the plan, housing associations and rural stakeholders that sign up pledge to:

- Work with and for rural communities, in accordance with the Rural Housing Alliance pledge.

- Increase the current level of housing supply in rural communities by 6% per year for each of the next five-years.

- Bid for at least 10% of Home England investment to deliver new homes in rural areas.

- Ensure that homes are delivered benefit the local economy, including the farming and food economy.

- Meet the needs of rural communities and contribute towards five key tenures, as appropriate – homes for affordable rent, market rent, affordable home ownership, self-build and market sale.

The Affordable Housing Commission recommendations for rural areas chime with the RSN and RHA in asking for regulatory reforms and tax incentives to encourage land owners to assist with housing provision for local people, with housing remaining affordable in perpetuity; and permitting Local Authorities to require some affordable housing for local people in rural schemes of less than 10 homes.

What emerges from all of this work is the need for a clear plan or strategy for rural areas that not only considers housing in a post-COVID, longer-term perspective, but also seeks to support those in the greatest need and links housing explicitly to other policy areas such as work, health and education. It needs to move away from crisis intervention to prevention – for example, we tend to respond to immediate needs particularly around ill health, food banks, homelessness, rather than thinking more holistically about providing affordable housing in rural places.

The National Planning Policy Framework encouraged larger scale developments and significant extensions to existing villages to meet supply. This led the Government to support a number of new garden villages across the country. This originally sought to support 23 places to deliver 200,000 homes by the mid-2020s. According to the prospectus, ‘this is not about creating dormitory towns, or places which just use ‘garden’ as a convenient label. This is about setting clear expectations for the quality of the development and how this can be maintained (such as by following Garden City principles). We want to see vibrant, mixed-use, communities where people can live, work, and play for generations to come – communities which view themselves as the conservation areas of the future. Each will be holistically planned, self-sustaining, and characterful’ (page 5). In June 2020, Transport for New Homes published research querying if 20 of these green communities were at risk of becoming car-dependent commuter estates, estimating they may develop up to 200,000 car-dependent households. One of the recommendations contained in the report was to build close to existing town centres or create strings of developments along public transport routes, rather than scattering developments around the countryside.

Broadway Maylan has developed the concept of the ‘reimagined village’ in seeking to reinvent the notion of village appeal and to expand it to broader target groups. This calls for the future village to be a valid economic force in its own right – connected, smart and green; and with something to offer everyone, irrespective of age, background, income, location or work/professional aspirations. They argue a number of components should be considered when designing a village, including scale and size; flexible and contemporary aesthetic housing; green space for active and healthy lifestyles; minimising environmental impact by building for a zero-carbon future; having an integrated community hub; providing places for modern working patterns; and introducing a range of sustainable transport infrastructure.

CPRE has long advocated for a ‘brownfield first’ policy. CPRE’s State of Brownfield 2020 reveals how there is enough brownfield land for 1,061,346 housing units over nearly 21,000 sites, covering almost 25,000 hectares. There is currently planning permission for 565,564 units, or 53% of the total brownfield housing capacity. And there is currently land provision for over 1.5 million homes using brownfield land and other land with planning permission, providing enough land to meet the government’s 300,000 homes a year target. According to CPRE, an approach to development that focuses on brownfield first would help to deliver homes where people really need them; closer to services, workplaces, public transport and shops. This would help us to protect and enhance the green spaces that are crucial for tackling the climate emergency, and safeguarding health and wellbeing.

Along similar lines, the Local Government Association and Cabinet Office have been running the One Public Estate programme since 2013 to support public bodies to get more out of their assets – including new homes and jobs. Covering the period up to 2019-2020, the programme was set to release land for some 25,000 homes. The programme cites the work of the London Borough of Croydon in identifying 15 publicly owned sites for regeneration which will see the development of 900 new homes and 7 new community facilities over a 5-year period. Analysis undertaken by the New Economics Found (NEF) found only 15% of homes being built on public land were classified as ‘affordable housing’; and only 2.6% of the homes being built were for social rent.

The Climate Change Committee found residential housing is the fourth largest contributor to UK emissions, accounting for 14% of the total. Two-thirds of homes currently have an EPC rating below the Government target of C and above. 2.4 million households (10% of all households) are living in fuel poverty. Only 1% of new homes are built to the highest energy rating. The UK’s legally binding climate change targets will not be met without near-complete elimination of greenhouse gas emissions from buildings – and efforts to adapt housing stock are lagging behind.

How can we provide more homes in the countryside without ruining it? A significant amount of land in public ownership is not needed to deliver public services and similarly, church/faith, charitable and private landowners may also have assets that could be harnessed to support the delivery of more affordable homes in rural places. While some organisations advocate for new rural settlements, others suggest we should utilise brownfield and protect the greenbelt. Rather than thinking on a settlement by settlement basis, how can we take account of the functionality and linkages between rural places?

If many of us are going to continue to live and/or work a bit differently, what will that mean for our rural communities? Watch this space.

………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Rural Housing Week is a campaign that takes place annually to showcase the work that housing associations do in rural communities. This year it is taking place 5-9 July. More information about the campaign and how to join in can be found here.

………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Jessica is a senior research fellow at The National Centre for Rural Health and Care (NCRHC) and researcher/project manager at Rose Regeneration. Her current work includes supporting health commissioners and providers to measure their response to COVID-19 and with future planning; providing the secretariat for the Parliamentary Inquiry into Rural Health and Care; and evaluating two employability programmes helping people furthest from the labour market. Jessica also sits on the board of a Housing Association that supports older and vulnerable people – and is developing schemes in rural places.

She can be contacted by email jessica.sellick@roseregeneration.co.uk.

Website: http://roseregeneration.co.uk/https://www.ncrhc.org/

Blog: http://ruralwords.co.uk/

Twitter: @RoseRegen

![fire extinguisher From community to brigade: the changing role of fire [cover] and rescue services in rural places](https://ruralwords.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/fire-extinguisher-1160x665.jpg)