Where does rural fit in the Government’s brand-new Freeport policy?

The Government wants to level up the UK by ensuring that towns, cities and regions across the country can benefit from global trade, inward investment and employment opportunities. In drawing on evidence from across the world, the Government is intending to create freeports across the UK. What does the UK freeports model look like and what might it mean for rural and coastal communities? Jessica Sellick investigates.

………………………………………………………………………………………………..

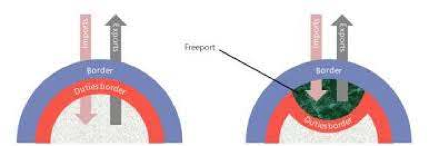

What are freeports? Freeports are ‘secure customs zones located at ports where business can be carried out inside a country’s land border, but where different customs rules apply. They can reduce administrative burdens and tariff controls, provide relief from duties and import taxes, and ease tax and planning regulations.’ In practice this means goods imported into a freeport are exempt from customs duties until they leave the freeport. If raw materials are brought into a freeport and processed into a final product before entering the domestic market, duties are only paid on the final goods. And if the goods are re-exported no duty is payable. Thus, while freeports are within a country’s geographical borders, they are outside that country’s customs border (illustrated in the diagram below).

The concept of freeports is not new and dates back centuries – from when traders operated off ships, moved cargo, and then reexported goods with little or no restrictions from authorities. More recently, freeports can be traced back to the 1960s and the establishment of ‘free zones’ adjacent to seaports and airports. The first free economic zone launched in Taiwan in 1966 and this was followed by Singapore in 1969 and South Korea in 1970. Freeports then diverged into several concepts – with the World Bank categorising free trade zones (FTZ), export processing zones (EPZ) and special economic zones (SEZ).

Here, a commitment to freeports was included in the 2019 Conservative Manifesto. Under ‘strengthen the union’, the manifesto sought to create new freeports to ensure ‘many places across the United Kingdom…have the opportunity to be successful innovative hubs for global trade’ (page 44); and ‘as part of our commitment to making the most of the opportunities of Brexit, and levelling up the nation, we will create up to ten freeports around the UK, benefiting some of our most deprived communities’ (page 57). In his first speech as Prime Minister on 24 July 2019, the Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP said “so let us begin work now to create freeports that will drive growth and thousands of high-skilled jobs in left behind areas.” On 2 August 2019 HM Treasury and the Department for International Trade announced the creation of a Freeports Advisory Panel to advise the Government on the establishment of up to ten freeports. The panel is advising the Government on the future design and operation of freeports as part of a future bidding process. The Government also held a series of industry roundtables to explore the different policy levers that could form part of a free zone offer and how best to develop a model that fits the UK.

Where are freeports? Countries around the world have adapted the model shown in the diagram above in operating freeports. For example, some have created tax incentives to drive investment in freeports, while others have reduced regulation or made infrastructure improvements around their freeports. There is no globally agreed upon definition of a freeport, which makes stating a definitive number of them and their locations difficult. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has opted to use the term SEZs to apply to all types of freeport. In June 2019 the UNCTAD published data on SEZs, finding at least 5,383 in 147 economies; of which 105 SEZs were in Europe. In developed economies (i.e., Europe and North America), most SEZs are customs-free zones and their role is to provide relief from tariffs and from administrative customs procedures, in order to support complex cross-border supply chains. In contrast, in developing economies the primary aim of SEZs is on attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). According to the UNCTAD more than 1,000 zones have been launched over the past five-years, and a further 500 are planned.

According to United States Congressional Research Service (CRS), as of 2018, there were some 195 Foreign-Trade Zones (FTZs) active in the United States during the year, with a total of 330 manufacturing operations. All States had at least one zone. The zone system accounted for 10% of all imports entering the United States, employing approximately 440,000 workers (or 3% of US manufacturing workers). The approximate location of FTZs is shown on the map below:

Issues for Congress, December 2019, page 8).

Between 2000 and 2018, the total value of goods received in FTZs increased from $238 billion to $794 billion. This was attributed to more goods entering US FTZs being of domestic status (i.e., goods that were produced in the US and good that have been produced abroad but entered the US customs territory for consumption); and the benefits associated with duty reduction on inverted tariff situations, customs inventory control efficiencies, and duty exemptions on exports. The FTZ Board grants authority to applicants to establish, operate and maintain zones. Once a zone has been established, the organisation that applied for the zone – which can be a public or private entity – is known as the grantee and responsible for providing the facility in line with FTZ regulations and reporting to the FTZ board on an annual basis.

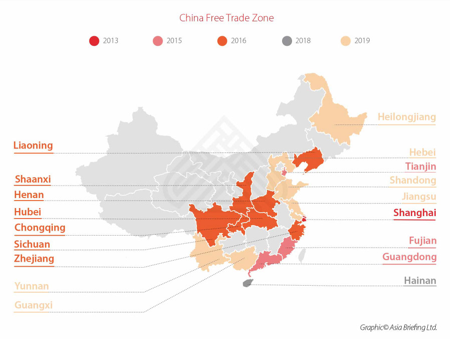

In 2018 China had 2,543 zones – more than half the world’s total. Their origins can be traced back to April 1979 and the creation of four special zones in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou and Xiamen. Today, Shanghai alone has 36 special zones ranging from industrial estates and export processing zones to hi-tech parks and an automobile city.

These zones have seen the Chinese Government introduce market-orientated reforms; acted as catalysts for allocating domestic resources; and attracted international capital, technology, technical and managerial expertise to stimulate industrial development. It is estimated that SEZs have contributed 22% to China’s GDP, 45% of total national FDI, and 60% of exports. SEZs are also estimated to have created over 30 million jobs.

Within the European Union, members of the customs territory may designate areas as ‘free zones.’ These are enclosed areas where non-Union goods can be introduced free of import duty, other charges (i.e., taxes) and commercial policy measures. There are currently 80+ free zones located within Europe – with the current list of states with zones including Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, and Spain. Many were originally set up as spaces to store goods in transit and simplify commercial operations.

Other examples of freeports include the Jebel Ali Free Zone in Dubai and Le Freeport, Singapore.

There are currently no freeports in the UK, although there is one on the Isle of Man [a British crown dependency that is neither part of the UK or EU]. HM Treasury has powers to designate freeports by Statutory Instrument under Section 100A of the Customs and Management Act (CEMA) 1979. Seven freeports did operate in the UK between 1984 and 2012 and were focused on customs benefits. In 2012, the five remaining freeports – at Liverpool, Prestwick, Sheerness, Southampton and Tilbury – ended when the statutory instruments lapsed.

A bespoke UK freeport model? In February 2020 the Department for International Trade published a consultation on Government proposals to establish freeports. In the document, the Government set out its aim to create up to 10 freeports across the UK: “These will be innovative hubs which boost global trade, attract inward investment and increase prosperity in the surrounding area by generating employment opportunities in some of our most deprived communities.” Under the strapline ‘boosting trade, jobs and investment across the UK’, the proposals have 4 objectives: (1) to enhance trade and investment across the UK; (2) to boost growth and highly-skilled jobs; (3) to signal that the UK is an attractive trade and investment location and open to business; and (4) to rebalance the economy and regenerate left behind areas.

During the consultation Government was seeking responses to 68 questions covering the following themes:

- Territorial scope – some policies relate to the whole of the UK, as well as some which are devolved. The Government intends to work in partnership with devolved administrations to develop the creation of freeports in all four nations.

- Tariffs – how will tariff inversion and deferral in freeports boost growth and facilitate trade?

- Customs – how could a freeport give businesses access to tariff inversion and deferral at lower administration costs than currently available?

- Tax – what tax and financial incentives have the best evidence for being effective at maximising the economic opportunities of freeports?

- Planning – how will specific planning freedoms for freeports maximise jobs and growth in their regions?

- Innovation – how can freeports deliver high-value jobs to surrounding areas and create hubs that link to academic and research institutions?

- Regeneration – How can Government / devolved administrations facilitate trade and investment?

In October 2020 the Government published its response to the consultation. 364 responses were received, and the document provides greater clarity about how freeports will operate across the UK. It describes how the UK Freeport model will maximise geographic flexibility and apply to areas with seaports, airports and rail ports, and to regions featuring multiple ports – no mode of port or area is excluded. The model will require a primary customs site designated in or near a port of any mode, and this can include sites in inland locations, so long as an economic relationship can be clearly demonstrated between the site and the port. Where bidders can make an economic case that they are required, the Government will allow multiple additional customs sites (known as ‘customs subzones’) to enable numerous sites to benefit from the customs model. Freeports will also include a single contiguous defined site within which tax reliefs will apply, building on the approach taken for existing Enterprise Zones in England and Wales. The primary customs site, tax site, and any additional subzones shall all be contained by an outer boundary. All measures (including any customs subzones and the planning, regeneration spending and innovation measures) should be applied within this outer boundary to ensure freeports are coherent, with a clear economic and geographic focus.

What are the benefits? Freeports are intended to stimulate economic activity – in both their designated area (e.g. through tax breaks) and more widely (i.e., through agglomeration effects). Some commentators distinguish between direct economic benefits (e.g. employment generation, export growth, foreign direct investment and increased Government revenue within the host country) and indirect economic benefits (e.g. export diversification, upgrading skills technology transfer).

In the United States, The Trade Partnership has measured the economic effects of FTZs on the communities in which the zones operate. They carried out a study to model changes for three economic measures [employment, wages and value added] in the FTZs compared to a similar economic community in the same region without a FTZ. The analysis reveals how all three economic measures increase in the broader community following the establishment of an FTZ and are greatest in the early years for employment and wages, and throughout the period for value added. For example, the establishment of the FTZ leads to an increase in employment growth (0.2%) and wage growth (0.4%) in years six and later and value-added growth (0.3%) eight years later. The study also found company access to FTZ benefits delivered wider effects through their supply chains located nearby (e.g. jobs, research and development, worker training).

Back in the UK, a Centre for Policy Studies report by Rushi Sunak MP in 2016 took the total number of jobs across the then 250 FTZs in the US (420,000), estimated these were additional jobs, and then adjusted for the size of the UK labour force to suggest the introduction of free zones in the UK would have the potential to create 86,000 jobs.

In 2018, the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Freeports endorsed the concept of ‘supercharged freeports’ as a model which Government could pursue to integrate freeports with Enterprise Zones to stimulate business growth, inward investment and support for new and expanding firms. Similarly, a trade campaign coalition, Port Zones UK, comprising airport and seaport operators is calling on the Government to grant special economic status to airports and seaports. An insights report by MACE in 2018 predicted an ‘optimistic scenario’ of gains from an assumed first-round price effect (i.e. a 1% decrease in the price of imports and exports leading to a 1% increase in the quantity of imports after 10 years) and also from induced agglomeration effects within the free zone zones (a boost in trade impacts of +150%). With an assumption that a 1% increase in trade translates to a 0.75% increase in gross value added (GVA) this would lead to a £12 billion boost in trade and a £9 billion increase in GVA. In turn, assuming that free zones activities lead to a creation of high-value-added jobs averaging £60,000 per job, a £9 billion increase in GVA would lead to the creation of 150,000 new jobs.

More recently, the benefits and opportunities around freeports in the UK have been framed around:

- The Levelling up agenda: a means of reviving disadvantaged towns and cities by attracting new investment, supporting enterprise and innovation, and creating new, skilled, jobs that local people can benefit from.

- Our departure from the EU: creating fresh impetus for a new and innovative domestic growth policy. Port Zones, for example, would bring together enterprise zones, development zones and free trade zones with the aim of stimulating international investment, reshoring manufacturing and lowering prices for consumers in a post-Brexit future.

- COVID-19 recovery: Data collected by the British Ports Association (BPA) found 55% of ports were not satisfied with the mechanisms and funding available to them during the pandemic. In response, the BPA is calling for medium term cash flow and business support, scaling up infrastructure and a bold freeports policy and port zoning strategy – including calling on Government not to cap the designation to 10 sites. A policy briefing from the Kiel Institute for The World Economy in April 2020 found almost all free zones were being adversely affected by the pandemic, through domestic measures to contain the virus, a drop in global demand, supply chain disruptions and/or a deterioration in the financial environment.

What are the risks? A survey undertaken as part of the UNCTAD team’s review of all 5,400 zones revealed that 22% were regarded as ‘heavily under-utilised/largely vacant’; a further 25% were ‘somewhat under-utilised or vacant’; and just 13% were ‘fully utilised’. The review states: “even where zones have successfully generated investment, jobs and exports, the benefits to the broader economy – a key part of their rationale – have often been hard to detect…Many zones operate as enclaves, with few links to local suppliers and few spill overs” (page 129). The review also found growth in SEZs between 2007 and 2012 was, on average, 2-5% lower than national GDP growth; therefore, suggesting these zones provide temporary stimulus during their development phase, with no direct correlation between incentives and export or job generation.

The UK Trade Policy Observatory (UKTPO) also signals caution around evidence of the wider economic benefits of freeports. They query previous research claiming free zones in the UK could generate up to 150,000 new jobs, add £9 billion a year to the UK economy and narrow the North-South divide because a smaller proportion would be genuine additional jobs and economic activity rather than just redistributed from elsewhere in the UK. They cite research on Enterprise Zones carried out by the Centre for Cities which found a total of 13,000 jobs had been ‘created’ between 2012 and 2017 as opposed to the 54,000 predicted, and how these were gross rather than net. Most of these jobs were in warehousing and similar and could make little contribution to long-term regeneration. The UKTPO has analysed three different approaches to tax inversion which allows importers to take advantage of the fact that they do not pay tariffs on intermediate goods imported into a Freeport, with a tariff being payable if a finished good leaves the FTZ leaves and enters the rest of the country after processing takes place. Regardless of the approach taken the analysis found introducing freeports in the UK would be unlikely to generate any significant benefits to businesses in terms of duty savings. Tariffs on intermediates tend to be low in the UK, typically lower than tariffs on final goods, which rules out duty savings in most cases. In addition, in those sectors for which they were able to identify any inversion, researchers predicted the benefits would be small and not have any material impact on the UK economy. There could only be large benefits from freeports, the UKTPO argues, if they were accompanied by generous tax or infrastructure benefits or major deregulation.

In 2019 the European Commission published an assessment of money laundering and terrorist financing risks affecting the internal market and relating to cross border activities. The report describes how freeports ‘may pose a risk as regards counterfeiting, as they allow counterfeiters to land consignments, adapt or otherwise tamper with loads or associated paperwork, and then re-export products without customs intervention, and thus to disguise the nature and original supplier of the goods. The misuse of free-trade zones may be related with infringing intellectual property rights, and engaging in VAT fraud, corruption and money laundering. In most EU free ports or customs warehouses, precise information on the beneficial owners is not available’ (page 5). These findings build on an earlier study from the European Parliamentary Research Service which looked at the freeport in Luxembourg and its (semi-) permanent storage of art and other high value assets and the introduction of anti-money laundering rules five-years earlier than planned. In January 2020, the EU introduced the fifth Anti Money Laundering Directive (AMLD5) in response to new levels of sophistication money laundering had attained and this now means Member States have to take extra measures to identify and report suspicious activities at the ports and zones.

What do freeports mean for rural and coastal communities? An article in the Financial Times in July 2020 suggested at least 21 locations were interested in becoming freeports. These included London Gateway, Bristol, Milford Haven, Liverpool, the Humber, Southampton, an area of South Wales, Tees Valley, Tyneside, East Midlands airport and Doncaster-Sheffield airport. Heathrow airport was reported to be interested in associated freeport status linking with another site.

In its report ‘ a licence to operate’, Port Zones UK included a case study of the Port of Milford Haven and Pembrokeshire. The report presents a stark picture of what might happen in Pembrokeshire if nothing is done to replace the oil and gas cargo flows and associated processing facilities, but also what could be achieved through some considered intervention, such as the creation of a free trade zone (FTZ) encompassing the area that currently forms the Haven Waterway Enterprise Zone. The report’s authors argue that the Port of Milford Haven’s internationally significant energy sector, large fishing port, abundant natural capital and associated infrastructure means it would not displace logistics or manufacturing from other ports where these activities are more prevalent. Ports UK is calling on the Government to accelerate planning processes, simplify legal and regulatory requirements so as to increase the viability of key anchor businesses and boost growth along the supply chain. The report further suggests that investment in the Port area could empower economic growth in Pembrokeshire’s rural economy and be more effective than previous ‘subsidy’ programmes the region has received in the past. Written evidence submitted by the Port of Milford Haven to the Welsh Affairs Select Committee suggested freeports status could help the wider Pembrokeshire economy as it would: (i) attract domestic and international investments contributing to business competitiveness; (ii) promote and accelerate low carbon innovation and creativity, improving labour supply and skills retention; (iii) improve transport technologies and other infrastructure in the region through targeted funding; and, (iv) contribute to regeneration in the region, strengthening the County’s brand and image.

How will freeports contribute to levelling-up, place-shaping and recovery from COVID-19 in ways that will benefit people and businesses in rural and coastal communities? How will freeports take account of geography (port-inland), communities (skills, housing), and infrastructure (broadband, road and rail links), in determining where they are located and driving benefits outside of their immediate footprint? The economic benefits of these zones around the world are often based on calculations or models – how will we track how their benefits (and the risks) in the UK? For example, what local employment will they create or sustain (i.e., high quality, highly skilled jobs or low-wage, low-skilled positions? What will the wage levels be? What types of contracts will workers be offered?) What new economic activity will they create or sustain – within the zone and in the wider economy – and how can they avoid displacing activities and investments from other businesses in the area?

From the UEA to the USA, and from China to Europe, over the past few decades the numbers and locations of freeports have expanded across the globe. In the UK, the Freeport Bidding Prospectus will be published by Government in the autumn and the Bidding Process for locations to become a Freeport in England will open by the end of 2020. What will this ‘brand-new, best-in-class, bespoke’ model look like in rural and coastal areas? And what will it mean for communities and businesses? Watch this space.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

Jessica is a researcher/project manager at Rose Regeneration and a senior research fellow at The National Centre for Rural Health and Care (NCRHC). Her current work includes supporting health commissioners and providers to measure their response to COVID-19 and with future planning; working with 8 farm support groups across England on a Defra funded resilience programme; and helping 3 places to develop proposals for a Town Deal. Jessica also sits on the board of a Housing Association that supports older and vulnerable people.

She can be contacted by email jessica.sellick@roseregeneration.co.uk.

Website: http://roseregeneration.co.uk/https://www.ncrhc.org/

Blog: http://ruralwords.co.uk/

Twitter: @RoseRegen