‘Working at scale’ – what do Primary Care Networks mean for rural communities?

Primary care services ‘provide the first point of contact in the healthcare system, acting as the front door of the NHS.’ It includes general practice, community pharmacy, dental and optometry services. It is also the route by which we most commonly access secondary parts of the NHS (e.g. planned hospital care, rehabilitative care, urgent/emergency care, out-of-hours/NHS 111, community health services, mental health services and learning disability services) as well as tertiary care (e.g. specialised treatment such as neurosurgery, transplants, forensic mental health services). Primary care has a pivotal role to play in Government ambitions for safe, personalised, proactive out-of-hospital care for all. This includes the establishment of Primary Care Networks (PCNs). Since April 2019 individual GP practices have been able to establish or join PCNs covering populations of between 30,000 and 50,000. What are PCNs and what do they mean for rural areas? Jessica Sellick investigates. ………………………………………………………………………………………………..

What are Primary Care Networks (PCNs)? While GP practices have been finding different way of working collaboratively for many years, the NHS Long Term Plan and NHS GP contact have placed a more formal structure around some of these ways of working.

According to NHS England, experience from around the country has shown that practices working collaboratively and more formally together at scale become more resilient, improve work-life balance for staff by deploying a wider team and are more effective at meeting the holistic needs of their patients and populations.

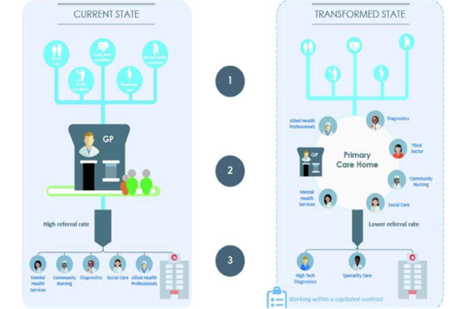

PCNs involve staff from practices and other local health and social care providers working in close partnership, as one team. They operate as a network, designing and delivering services collectively that best meet the needs of their local communities. The majority of care will continue to be based around general practice and GP surgeries – but PCNs provide a means of offering additional services that are either too big to be in every practice and/or that do not need to be delivered in a hospital setting.

The core characteristics of PCNs include:

- Practices working together and with local health and care providers ‘around natural local communities that make sense geographically, to provide coordinated care through integrated teams.’

- Providing care in different ways to match different people’s needs – including flexible advice and support and multidisciplinary care for people with complex conditions.

- Focus on prevention, patient choice and self-care – supporting patients to make choices about their care and connecting them with statutory and voluntary services.

- Use of data and technology – to assess population health needs and inequalities, and to inform the design and delivery of different care models.

- Making best use of collective resources across practices – leading to greater resilience, more sustainable workloads and access to a larger range of professional groups.

PCNs are intended to be small enough to maintain the strengths of general practice (e.g. continuity of care) but large enough to support the development of integrated teams made up of several professional groups.

The diagram below illustrates the difference between the current way primary care operates and how it will do so under PCNS.

The exact size of PCNs is determined locally. PCNs can be structured in a number of ways, with the decision on how a network operates down to an agreement between the general practices in membership.

PCNs are intended to build upon ‘primary care home’ (PCH). This is a model developed by the National Association of Primary Care (NAPC) to bring together a range of health and social care providers to work together to provide enhanced personalised and preventive care for local communities. PCH initiatives have been running for three years. NAPC has been supporting the development of PCNs, through both organisational development and offering a Diploma in Advance Primary Care Management to support staff to manage primary care at scale.

Why have they been set up? The NHS Long Term Plan contained proposals to establish PCNs to ‘provide flexible options for GPs, and wider primary care teams’ as part of an extra £4.5 billion of investment to fund community multidisciplinary teams. As part of a set of multi-year contract changes, individual practices in a local area will enter into a network contract – as an extension of their current contract – and have a designated single fund through which all network resources will flow. Most Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) have local contracts for enhanced services and these will normally be added to the PCN contract. Expanded neighbourhood teams will include staff such as GPs, pharmacists, district nurses, community geriatricians, dementia workers and Allied Health Professionals (AHPs) e.g. physiotherapists and podiatrists/chiropodists, who will be joined by social care and the voluntary sector providers. Within the Long Term Plan, PCNs are to be offered a new ‘shared savings’ scheme so that practices benefit from reductions in avoidable A&E attendance, admissions and delayed discharge, and the streamlining of patient pathways to reduce avoidable outpatient visits and over-medication. The Long Term Plan also sets out a desire for stronger links between PCNs and local care homes, emergency services, local community services (e.g. frailty services) and social prescribing (providing patients with links to local groups and activities). PCNs are also expected to support early diagnosis, as well as to find and treat people with high risk conditions.

PCNs also build upon the findings of the GP partnership review. In recognising how the average size of individual practices is increasing, the number of salaried (employed) GPs is increasing and the move towards more part-time and flexible working; the review made seven recommendations. They were: (1) reducing the personal risk and unlimited liability currently associated with GP partnerships; (2) increasing roles and funding for General Practitioners; (3) increasing the range and number of healthcare professionals to support patients in the community; (4) increasing the time medical students spend in general practice through primary care partnerships; (5) ensuring practice are more sustainable through the establishment of PCNs; (6) ensuring general practice has a representative voice at a system level; and (7) enabling practices to be more efficient through IT and innovative digital services.

NHS England and the British Medical Association’s (BMA) General Practitioners Committee (GPC) have agreed a five-year GP (General Medical Services) contract framework from 2019-2020. The contract increases general practice funding by £978 million per year by 2023-2024 and introduces a PCN contact from 1 July 2019 as a Direct Enhanced Service (DES). The 2019-2020 Contract Agreement includes additional funding for general practices to engage and participate in a PCN. Should a practice not wish to engage in the DES, the respective practice will not qualify for the additional monies and the rest of the network will take responsibility for the provision of network level services to that practice’s patients. The DES is being phased in over the next five years and will eventually cover seven service areas (medication, health in care homes, anticipatory care, personalised care, early cancer diagnosis, cardiovascular disease and inequalities).

Also referred to as the Primary Care Network Contract, the Direct Enhanced Service (DES) is designed to support practices to develop and implement PCNs by working with neighbouring practices in their areas. The DES consists of a network agreement specifying the governance and financial structure of the PCN along with details of funding, workforce and a timetable. In signing up to a DES, PCNs will need to make a submission to their Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) including details of member practices, the PCN list size, a map showing the PCN area, a single practice that will receive funding on behalf of the PCN and a named Clinical Lead. The deadline for submissions was 15 May 2019.

According to The King’s Fund, PCNs are being established to respond to three challenges facing the NHS: (i) to address workforce recruitment and retention – by targeting specific professions including pharmacists and physiotherapists to start with; (ii) to properly ensure the voice of general practice is part of, and fully integrated with, community and other services; and (iii) to improve population health – covering a whole range of issues from preventing coronary heart disease to tackling neighbourhood health inequalities.

In the meantime, NHS England has produced a Reference Guide, frequently asked questions (FAQs) podcasts and details about events and webinars for health and care professionals to find out more.

From a patient perspective, people should experience more joined up services, access to a wider range of professionals and diagnostics in the community, different ways of getting advice and treatment (e.g. digital and face-to-face services), shorter waiting times and greater involvement in decisions about their care within a PCN. Within local communities, PCNs are intended to increase the focus on prevention and helping people to take charge of their own health.

From a general practice perspective, clinicians should experience more efficient use of resource leading to greater resilience (staff, buildings); a more sustainable work-life balance; a more satisfying workload; greater influence on decisions made elsewhere in the health system; and the ability to provide better and more timely treatment to patients.

For other health and care partners, including Local Authorities, PCNSs are expected to lead to greater cooperation across organisational boundaries and a wider range of services being made available in local communities so patients do not have to default to the acute [hospital] sector.

How do they work? NHS England has developed a ‘maturity matrix’ for PCNs as part of a recognition that networks will progress at different rates. The matrix covers:

- Foundations for transformation: develop a plan, engage with primary care leaders and other stakeholders, provide headroom to make change and ensure you have the people skills and financial commitment to fulfil primary care transformation.

- Step 1: identify PCN partners, analyse outcomes and resource use between practices, understand population groups and their resource use, integrate primary care teams with social care and the voluntary sector, standardised state models of care, take steps to ensure operational efficiency, and ensure primary care has a seat at the table for system strategic decision making.

- Step 2: have a defined future business model, function interoperability within the network, ensure shared access to information and decision making, new models of care in place for most population segments, networks can see their impact on system performance, and play an active role in system operational decision making.

- Step 3: the business model is fully operational, IT / workforce / estates fully interoperable, systematic population health analysis, new models of care in place for all population segments, collective responsibility for available funding, and providers are full decision makers of Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) and working in tandem with other partners allocating health and care resources.

The primary care model being developed by each network fits with Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs) and Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) in operating at three system levels: (1) neighbourhoods – with PCNs providing multidisciplinary care; (2) places – with PCNs integrating care between hospitals and Local Authorities; and (3) systems – with PCNs participating as an equal partner in decision making. STPs/ICSs must include a primary care strategy – they will be developing their strategies in autumn 2019 in response to the Long Term Plan.

The PCH has produced some examples, NHS England published some case studies and the BMA a handbook all illustrating what a PCN may look like in practice.

What do they mean for rural areas? PCNs, by their very voluntary nature, suggest a mixed approach to their formation and delivery will emerge. So what might PCNs mean for rural residents? I offer three points.

Firstly, the term ‘working at scale across practices’ which can be traced back to the General Practice Forward View, takes on renewed significance with PCNs as NHS England is committed to 100% geographical coverage of the Network Contract DES by 1 July 2019. It is NHS England’s intention is for practices to work together ‘around natural local communities that geographically make sense, to provide coordinated care through integrated teams.’ NHS England anticipates that practices will work together in ‘geographically coterminous areas, rather than because of historic performance.’ PCNs are intended to have a defined patient population of at least 30,000 and not to exceed 50,000. The Long Term Plan suggestion of 30,000-50,000 registered patients as the desired size originates from the findings of the PCH model. According to the BMA handbook, ‘while there is no maximum size of a PCN, and commissioners can sign off on PCN proposals that go over 50,000, it is at around this size that networks will best keep the features of traditional community-based general practice, combined with the benefits of integrated working across a locality…Only in exceptional circumstances will networks be allowed to cover a population smaller than 30,000; for example, in rural areas where reaching a 30,000+ population causes geographic problems.’ It is not anticipated that PCNs will cross CCG boundaries.

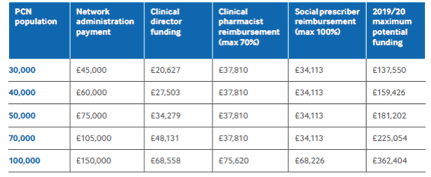

It is expected that funding will vary by the population covered by the PCN (BMA handbook page 16):

Research by Nuffield in January 2019 found evidence of the additional and unavoidable costs of delivering health care in rural settings and highlighted the implications of this ‘funding gap’ on wider quality and sustainability issues.

The way the NHS funding model currently works is based upon economies of scale. While providing all patients with equal access to its services at the same level of quality; how will PCNs take account of different types of rural and coastal populations and places? What does ‘traditional community based practice’ look like in rural areas – and how can PCNs support it? Where are there gaps in coverage and why?

Secondly, will PCNs lead to better recruitment and retention of the health and care workforce in rural places? All PCNs must have a named clinical director – but how that post is filled is determined by each PCN. Their role is to provide appropriate leadership to establish and develop a successful network. The DES provides workforce reimbursement for the network covering a number of specified health professions and is designed to allow the PCN to build up an expanded primary care team. In year 1 this will include funding for a clinical pharmacist (funded 70% by NHS England and 30% by the PCN) and a social prescriber (funded 100% by NHS England). The majority of the workforce that will be introduced into PCNs over the next five years will normally be set at a 70/30 NHS England / PCN funding split. This could include roles such as physician associates, physios and community paramedics.

PCNs are expected to form the basis of people themselves being the best navigators of their care. The personalised care operating model sets out the infrastructure role of PCNs in supporting local social prescribing schemes, with every GP practice having access to a link worker – which will see the recruitment of 1,000 social prescribers by 2020-2021 and up to 900,000 people benefiting from the support they provide by 2023-2024.

PCNs will also be expected to work alongside other voluntary and community sector organisations to help alleviate workload pressures on practices and allow GPs to concentrate on the most complex patient cases.

In October 2018, the National Centre for Rural Health and Care (NCRHC) published the findings of a study into rural workforce issues in health and care. While securing staff to deliver high quality health and care in rural areas (now and in the future) is crucial, the research revealed 9 challenges affecting the recruitment and retention of staff:

- Rural areas are characterised by the disproportionate out-migration of young adults and in-migration of families and older adults.

- This means that the population is older than average in rural areas – this has implications for demand on health and care services and for labour supply.

- Relatively high employment rates and low rates of unemployment and economic inactivity mean that the labour market in rural areas is relatively tight.

- There are fewer NHS staff per head in rural areas than in urban areas.

- A rural component in workforce planning is lacking.

- The universalism at the heart of the NHS can have negative implications for provision of adequate, but different, services in rural areas.

- The conventional health service delivery model is one of a pyramid of services with fully-staffed specialist services in central (generally urban) locations – which are particularly attractive to workers who wish to specialise and advance their careers.

- Rural residents need access to general services locally and to specialist services in central locations to provide the best health and care outcomes.

- Examples of innovation and good practice are not routinely mapped and analysed which hinders sharing and learning across rural (and urban) areas.

For me, the research highlighted the lack of a spatial component in workforce planning. The research analysed 10 STP plans in detail – with these areas chosen because they have at least double the share of rural population than England as a whole. Across these 10 plans there are fewer than 50 references to ‘rural’. None of the plans makes a clear link between the rural area they cover and the workforce challenges that they face. While RSN members recognise and champion the heterogeneity of rural areas– geographically and socioeconomically – this spatial component is not always taken into account in health workforce planning.

In May 2019, the Nuffield Trust, assessed the number of GPs compared to the size of the UK population over time. The analysis revealed how the number of GPs relative to the size of the population has fallen in a sustained way for the first time since the 1960s. For the overall number of GPs to have kept pace with the number of the people in the UK since 2014 we would have needed some 3,400 more GPs.

Will PCNs provide a way of addressing existing recruitment and retention challenges in primary care? Or will they find it difficult to do so as they are already running and trying to change / reorganise whilst getting on with the demanding day job? How can (and will) PCNs address some of these rural issues they face, particularly through working with the voluntary and community sector and local groups in the design and delivery of primary care services? For rural residents, in theory, PCNs offer the potential to provide a mix of proactive and preventative support, emergency and rapid support and ongoing support (for complex conditions) but this will only happen if existing and new staff can be both attracted and retained.

Thirdly, will PCNs provide a better means for ensuring the voices of rural communities and clinicians are heard and acted upon at a system level? NHS England wants patients and the public to be involved in the work of PCNs in a meaningful way. It’s guidance on patient and public engagement sets out web based resources and best practice for both greater shared decision making between patients and clinicians and for engaging the public in a discussion about services. Healthy Conversation 2019, for example, precedes PCNs and is a discussion across Lincolnshire about what (and how) we need to change to ensure that our health, and health services are fit for the future. PCNs are expected to engage with STPs and ICSs to shape their strategic direction and align population care on a wider scale. PCNs are also expected to focus on prevention and personalised care – delivering a set of seven national service specifications. Five will start by April 2020: structured medication reviews, enhanced health in care homes, anticipatory care (with community services), personalised care and supporting early cancer diagnosis. The remaining two will start by 2021: cardiovascular disease case-finding and locally agreed action to tackle inequalities.

The health care system already collects an enormous amount of data and feedback from patients at local and national levels. Do PCNs provide new opportunities for the health system to think differently about how it listens and acts on insights from residents and patients? Where will their voices be, for example, in the development of local system plans? How can PCNs make this – and their work with voluntary and community sector organisations and local groups – essential to how they operate? Will there by capacity and capability in this new system to share learning and practice?

Where next? The current model of health care has been focused on hospital-based care and treating diseases and illnesses. There is now widespread acceptance, within the system, that this model is not sustainable and that coordinated, integrated and multidisciplinary care at the local/neighbourhood level is needed to prevent ill-health. PCNs offer a means of doing this. Practices have been meeting to discuss forming PCNs since January 2019 and the networks themselves are expected to go live in July 2019. Are we giving PCNs too much to do – and too soon – or do they provide an ambitious response to address the challenges that general practice faces, particularly in rural areas? Watch this space…

………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Jessica is a senior research fellow at The National Centre for Rural Health and Care (NCRHC). The NCRHC is a Community Interest Company, national in scope and with a Headquarters in Lincolnshire, and focuses on four principal activities: data, research, technology and workforce.

The NCRHC has joined with the Rural Services Network (RSN) to launch the affiliated Rural Health & Care Alliance – a membership organisation dedicated to providing news, information, innovation and best practice to those delivering and interested in rural health and care across England. More information about the RHCA – and how to join – can be found here: https://www.rsnonline.org.uk/page/about-the-rhca

Jessica is also a researcher/project manager at Rose Regeneration. Her current work includes evaluating two veteran support projects (in Cornwall and North Yorkshire); supporting public sector bodies to measure social value; and evaluating a series of community safety and crime reduction projects.

In her spare time Jessica sits on the board of a housing association.

She can be contacted by email jessica.sellick@roseregeneration.co.uk or telephone 01522 521211. Website: http://roseregeneration.co.uk/https://www.ncrhc.org/ Blog: http://ruralwords.co.uk/ Twitter: @RoseRegen