Developing a theory of change: mapping out the “missing [rural] middle” or (re)describing a process?

A ‘theory of change’ involves people coming together to think about the difference that they want to make (and with whom), the context within which they work and what activities they need to undertake to lead to this positive change. But does a theory of change have a transformative effect on community projects or is it retrospective in leading us to reflect on what we’re already doing? Jessica Sellick investigates.

………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Where does the term ‘theory of change’ come from?

The term can be traced back to the 1950s and The Kirkpatrick Model. Developed by Donald Kirkpatrick to evaluate training courses; the model moves from Level 1 ‘reaction’ (how participants react to the training), to Level 2 ‘learning’ (if participants have understood the training), Level 3 ‘behaviour’ (if they are using what they have learned) and Level 4 ‘results’ (if the training has had a positive impact of the organisation). Then, in the 1960s, the term ‘Programme Theory’ emerged. This consists of a set of statements that explain why, how and under what conditions a programme operates as well as the predicted outcomes and requirements necessary to bring about these desired effects.

The Logical Framework Approach (LogFrame) was developed by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in the late 1960s – and it subsequently became a requirement for all projects funded by the organisation to use it from 1970. The approach consists of a four by four matrix which aims to encourage people to consider the wider aspects of their project by thinking about goals, purpose, outputs, activities, indicators and assumptions. Variations of this tool include Goal Directed Project Planning (GDPP) and Objectives Orientated Project Planning (OOPP).

In the 1990s, the Aspen Institute began looking at the challenges of evaluating complex community or social change programmes. In holding a Roundtable on Community Change, it was Carol Weiss who popularised the term ‘theory of change’ in writing about the need to advance theory-based evaluation (TBE). Consequently, the term ‘Development Evaluation’ (DE) was used by Michael Quinn Patton, Patricia Rogers and others working in the social innovation sector.

But theory of change can also be traced back to ‘logic models’ (a visual way of organisations information and displaying thinking) and the impact pathway approach (IPA), a systematic method for identifying and tracing the effects of air pollution.

The term ‘theory of change’, then, emerges from three main scholarly lines of thought: (1) international development, (2) social development and (3) evaluation.

What is a ‘theory of change’?

According to the Centre for Theory of Change it is ‘a comprehensive description and illustration of how and why a desired change is expected to happen in a particular context. It is intended to ‘map out’ or ‘fill in’ the “missing middle” between what a programme or change initiative does (its activities or interventions) and how these lead to desired goals being achieved (its outcomes and longer term change).

Comic Relief describes it as an ‘ongoing process of reflection to explore change and how it happens…”it locates a programme or project within a wider analysis of how change comes about…it is often presented in diagrammatic form with an accompanying narrative summary.”

According to the NCVO, a theory of change “shows how you expect outcomes to occur over the short, medium and longer term as a result of your work…it can be developed at the beginning of a piece of work [to help with planning], or to describe an existing piece of work [so you can evaluate it].”

For me, a theory of change is a map setting out change; and what, why, when and how a project or intervention is contributing to that change. It shows the links between inputs, interventions, outcomes and longer term goals that all lead to change.

Who is using it – and why is it important?

As an approach, theory of change can be used for an entire organisation, a group of organisations/partnership or an individual project, programme or activity.

Some organisations develop a theory of change when designing an intervention: to show how, in a logical sequence, the organisation’s strategy links to its activities and the outcomes it wants to achieve. Other organisations develop a theory of change mid-way through an intervention – to monitor progress so far, measure outcomes and make any adjustments. While other organisations develop a theory of change at the end of their intervention – to evaluate their impact.

International development groups and organisations are using theory of change as part of a recognition that if programmes are to be successful they need to be integral to local communities – for example, see the ecosystem services for poverty alleviation programme (ESPA) theory of change approach; the Asia Foundation; the Overseas Development Institute’s collaboration with the Asia Foundation and London School of Economics; and Oxfam’s approach (including how it has been applied to community development).

In community and social development, a theory of change is often seen as a tool to develop solutions to social problems. The Community Builder’s Approach is a method that community groups can use to think about what is required to bring about social change. For other examples see the youth unemployment project (by NCVO); community cooking (TSIP) and after school network (in California).

I use theory of change as an evaluation tool –when planning a project, mid-way through a project and/or at the end. Elements that I include when developing a theory of change comprise:

- Setting out the initial condition(s) for change: why the project is needed (context).

- The activities the project is delivering or will deliver that might lead to change.

- For which client group/s these activities are happening.

- The outputs: the effects and results of these activities with the client groups.

- The outcomes: the change(s) that result from the activities leading to impact – these can be short, intermediate or longer-term. These could be things within the organisation or external to it (i.e., they may relate to policy or a funding body).

- Longer term change: the ultimate difference that the project seeks to make.

Depending on when I am developing a theory of change I review all the data and documents about the project and then sit down – sometimes multiple times – with people involved in designing, delivering and using the project (as well as some external stakeholders); and I also consider the broader context in which the project sits.

Rather than a static diagram that sits-on-a-shelf, I regularly review the theory of change with people involved in the project so that it can be updated through an iterative real-time process. This shared understanding [among service users, volunteers, delivery staff, trustees and funders] is key to understand how the project is trying to make a difference.

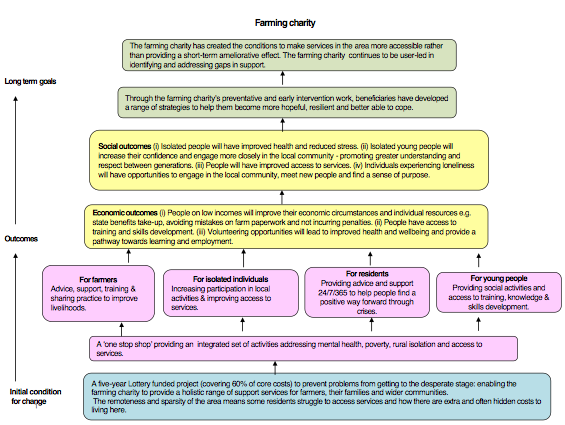

An example of a theory of change developed with a farming charity:

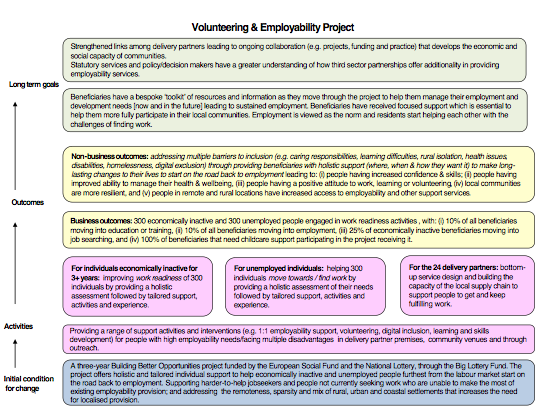

An example of a theory of change for an employability project:

Theory of change is important because it can help you ‘reality check’ what you are doing. The approach fits within Nesta’s standards of evidence by providing a means for you to describe ‘what you do and why it matters, logically, coherently and convincingly’ (level 1). Theory of change is also referenced in HM Treasury’s Magenta Book in setting out how evaluation should be a ‘systematic and cumulative study of the links between activities, outcomes and the context of a policy intervention’ (page 57).

A theory of change can provide a lens to help you and others ask simple but important questions about what you are doing and why – leading to a common understanding and clarity amongst a wide constituency about what you are working towards.

It can also support critical thinking – it is a process rather than a final product meaning the information will be tweaked over time; providing a rough guide as to what is working well and if there are any gaps emerging. It is not a standalone diagram, rather it should be looked at on a regular basis to think through: how does this fit into our strategic vision and business plan? What data and information do we need to collect to measure change? Are we experiencing project drift? Are we looking to scale up (or scale down) what we are doing? Where next?

It can assist you in explaining to funders and stakeholders how you wish to improve your services and/or sector – by explaining succinctly, on one sheet, with realistic timeframes and trajectories, what you are seeking to do.

For me, a theory of change also provides opportunities to think through some tricky evaluation questions:

- What would have happened anyway if the project had not taken place (deadweight)?

- Are other organisations also supporting the same client groups so could also claim some of these outcomes (attribution)?

- Is the project unintentionally competing with similar initiatives being delivered by other organisations in the area (displacement)?

- How long will the warm positive glow experienced by the client groups last for (drop off)?

This also provides opportunities to consider if a project is delivering any positive (or negative) unanticipated outcomes – and this often opens up conversations around business planning, legacy, sustainability and income generation.

For rather thanof change?

Critics argue that while the purpose of a theory of change is to guide action it tends to be backward looking: describing the change process itself rather than explaining the effect and impact of outcomes. Does theory of change help you know what works and does not work or does it squeeze out this space for learning?

A theory of change may reflect what an organisation is already doing rather than hold it to account to look again at its activities, resources, outcomes and so on. Does theory of change help you take into account the changing external environment in ways that make you think differently about the activities you provide? Or are we too focused on what we are doing?

Theory of change places an organisation, project or programme at the centre of the picture which may lead context to be neglected. For critics, too much emphasis is being placed on how we are seeking to change others rather than on holding a mirror up to what we are doing.

It has also been considered too technical in emphasising inputs, interventions and outputs rather than focussing on people and relationships.

It may also encourage you to think about your project in linear terms – as a simple flow from cause to effect rather than something more complex. Is it too simplistic to use unlabelled arrows and a series of boxes to show the links between different components?

In presenting a positive view it can lead you to over-state the contribution of your project or intervention. Are we trying to prove what we are doing or improve?

Finally, a theory of change does not insulate a project or programme from failure.

Developing theories of change for rural communities?

In a rural context this raises five questions to consider (as a starting point):

- How does your theory of change capture the needs and aspirations of rural communities – is it something that everyone broadly agrees with?

- How does your theory of change capture variations in location or setting – what does a project or initiative look like in a (different kinds of) rural places [sparsity]?

- How does your theory of change capture the additional costs and complexities of delivering in rural places?

- How does your theory of change capture the wider context – how does it fit with other public, private, voluntary and community sector bodies and/or funders?

- How does your theory of change guide your data and information gathering – are there milestones and indicators so you can monitor and measure your impact?

Theories of change come in all shapes and sizes – from wiring diagrams and flow charts through to systems maps. They can provide a practical means of supporting and improving what we are already doing – or thinking of doing. Yet at the same time we also need to be mindful that we query, adapt, amend and – above all – apply a rural lens through what we do.

………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Jessica is a researcher/project manager at Rose Regeneration. Her current work includes evaluating two veteran support projects (in Cornwall and North Yorkshire); supporting public sector bodies to measure social value; evaluating a series of community safety projects; and undertaking a piece of work on migration.

She is also a senior research fellow at the National Centre for Rural Health and Care (https://www.ncrhc.org/).

In her spare time Jessica sits on the board of a housing association.

She can be contacted by email jessica.sellick@roseregeneration.co.uk or telephone 01522 521211.

Website: http://roseregeneration.co.uk/

Blog: http://ruralwords.co.uk/

Twitter: @RoseRegen